A Spirituality of Action: Christ’s Apostolic Model of Contemplation and Action

The Church exists for the purpose of sharing the Gospel and inviting the whole world to salvation and relationship in Christ. Consequently, “a Christian vocation by its very nature is also a vocation to the apostolate,” that is, a call to mission.[1] Many are enthused to receive such a dignified call, but these sentiments are not self-sustaining. The enormity of evangelizing the whole world, which initially can provoke excitement, often degrades to discouragement amidst incessant demands for action. There is always something more to do in this fallen world, and apostles can begin to question, “What time do I have to pray with so much to do? Wouldn’t it be more generous if I dedicated myself more to doing these good things? Isn’t the Lord also present in these good things? Could it be that I’m even being lazy or selfish by prioritizing a life of prayer? Aren’t there so many souls that need to be saved? How can I allow myself to stop?” This line of questioning, however, overemphasizes the person’s action above God’s, and if unaddressed, it leaves a person destitute of faith and energy.

St. John Paul II proposes to the Church’s apostles a safeguard against this kind of breakdown: “a solid spirituality of action.”[2] As the name suggests, it is a way of living and acting built upon the spiritual life. John Paul II describes it as a unity of contemplation and action, of communion with God that inspires ardent action.[3] This call to contemplation places Christians in contact with the source and fulfillment of their action. The saintly pope explains that the Church’s universal mission is to orient humanity’s gaze, awareness, and experience “towards the mystery of God,” particularly the redemption accomplished by Jesus Christ.[i4] In other words, the nature of apostolate is to draw all people to encounter God, to contemplate him and his saving work. If missionaries neglect their call to contemplation, they betray their own mission. However, when action is united to contemplation, apostles are able to see “God in all things and all things in God,” allowing “the most difficult missions to be undertaken” because they literally never lose sight of God.[5]

While the term “spirituality of action” was coined by St. John Paul II, the concept is anything but novel. Whether it is the Benedictine motto of ora et labora, prayer and work,[6] or the designation of “contemplatives of action” commonly applied to the Jesuits,[7] the unity of contemplation and action has been safeguarded by monks and missionaries alike throughout history. This spirituality, however, is not reserved solely for consecrated members of the Church. The Second Vatican Council calls the laity to inform their actions with their life in God because “their works, prayers and apostolic endeavors, their ordinary married and family life, their daily occupations, their physical and mental relaxation, if carried out in the Spirit, and even the hardships of life, if patiently borne—all these become ‘spiritual sacrifices acceptable to God through Jesus Christ.’”[8] Put simply, there is no calling that favors contemplation or action at the expense of the other. Every Christian is called to a relationship with God that overflows into action, and the spirituality of action is the apostle’s response to this call.

The Eucharist: The Tree of Life

At the origin of human history lies a pivotal moment—the fateful bite from the forbidden fruit in the Garden of Eden. However, this profound narrative doesn’t conclude with the original sin; it finds its ultimate fulfillment in the taste of the Eucharist. Through the sense of taste, which once led to humanity’s fall, we now receive spiritual nourishment and the grace of eternal life, all made possible through the loving sacrifice of Christ.

In the Garden of Eden, God placed two trees—the Tree of Life and the Tree of Knowledge of Good and Evil. While Adam and Eve were commanded not to eat from the Tree of Knowledge, they were free to partake of the Tree of Life, which held the gift of immortality and eternal communion with God.

Tragically, temptation lured Eve into believing the serpent’s deceitful words—that eating the fruit from the forbidden tree would make her wise like God. She tasted the fruit and shared it with Adam, thus disobeying God’s command.

As a consequence of their disobedience, sin entered human nature, and God, in his mercy, expelled them from the Garden of Eden. This act of divine love spared them from eternal separation from God in their fallen state. Eating from the Tree of Life while in a state of sinfulness would have meant an eternity estranged from him. God had angels guard the Tree of Life in his infinite wisdom, ensuring that Adam and Eve would not eat from it on their way out. “He expelled the man, stationing the cherubim and the fiery revolving sword east of the garden of Eden, to guard the way to the tree of life” (Gn 3:24).

This denial of access to the Tree of Life foreshadowed the need for a Savior to redeem the human race from sin and open up access to eternal life through faith and grace. That Savior is Jesus Christ, whom the New Testament calls the “last Adam” (1 Cor 15:45). Just as Adam’s sin brought death into the world, Christ’s sacrificial death on the Cross brings redemption and the promise of eternal life. Thus, the image of the Tree of Life profoundly connects to the Cross on which Jesus was crucified—a Cross made of a tree, symbolizing the tree of the Fall being redeemed by the tree of the Cross.

The Passover and the Eucharist as Redemptive Sacrifices

I suspect that most Catholics who have some familiarity with the Bible and the Eucharist could tell you that the Eucharistic celebration, rooted in the Last Supper, has connections with the Passover of Exodus and Jewish practice. We know that Jesus celebrated the Last Supper in the context of the Passover Feast and that he and his apostles used some of the same foods used at Passover, such as unleavened bread and wine. I’m not sure that most of us, however, appreciate the depth of the connections. They are not just historical or biblical trivia, either—they reveal the profundity of God’s plans for us in the Eucharist. This is especially true of the korban pesach, the sacrifice of the lamb. Most of the time, we overlook the fact that the lamb was offered as a redemptive sacrifice. It was offered in place of the Israelites, who deserved death just as the Egyptians did. When we understand this, we can begin to truly appreciate the depth of God’s mercy in giving his people the perfect sacrifice after centuries of imperfect ones.

Setup for Passover: The Plagues

To begin, we need to understand the background for the Passover in the ten plagues, which are recounted in chapters 7–11 of the Book of Exodus. After the encounter with the Burning Bush in Exodus 3, Moses and his brother Aaron tell Pharoah to let the Chosen People leave Egypt. Pharoah refuses. In response, God begins to send plagues, wonders intended to display his power. Pharoah’s heart is so hard, however, that God continues to display greater and greater power until we come to the eve of the tenth and final plague: the death of the firstborn. This is a plague that we regularly misunderstand, but it is impossible to grasp the whole meaning of the Passover without an accurate understanding of this plague.

Our main problem is that we look at the death of the firstborn, and the plagues in general, as punishments intended to hurt the evil Egyptians. There certainly is an element of punishment here, but the primary function of the plagues is to display the power and rights that the God of Israel has not only over his own people but over all of nature and, ultimately, over human life. In Exodus 7:4, when God foretells the plagues to Moses, he does call them “great acts of judgment.” However, he goes on to state the purpose of these acts: “The Egyptians shall know that I am the LORD” (7:5). The plagues then build upon each other, successively showing Pharaoh God’s power over the Nile, over crops, over livestock, over the human body, and over the sun, which the Egyptians considered a god. Ultimately, Pharaoh only realizes that the God of Israel has power over life itself when the tenth plague takes the lives of Egypt’s firstborn. Remember this as we discuss the Passover meal.

Missionary Worship

There is an interesting phenomenon that occurs in nearly every culture across history: man ritualizes worship. All over the world the similarities are astounding—animal sacrifices, burnt offerings, gifts of grain, the joy of ecstatic praise. It points to a universal sense within man that not only recognizes that there is a God but also knows that man is called to represent the created order before the Creator. This universal orientation toward the divine can help us recognize what it means to become Eucharistic missionaries.

There is an interesting phenomenon that occurs in nearly every culture across history: man ritualizes worship. All over the world the similarities are astounding—animal sacrifices, burnt offerings, gifts of grain, the joy of ecstatic praise. It points to a universal sense within man that not only recognizes that there is a God but also knows that man is called to represent the created order before the Creator. This universal orientation toward the divine can help us recognize what it means to become Eucharistic missionaries.

A Little World

Man is similar to the dust of the earth, the plants that grow, and the animals that move and feel. Yet, he isn’t confined to a “fixed pattern” like the plants and animals; rather, he has been given “the privilege of freedom” like the angels.[1] He is a “little world” arranged in harmonious order in which matter is given voice, elevated, and ennobled by its participation in man’s freely offered “spiritual worship” (Rom 12:1).[2] He has a deep capacity to entrust himself. Standing at the summit and center of creation, he is capable of free obedience to God, which allows for the transformation of his life into a living liturgy of praise.

As matter and spirit, man is also capable of seeing beyond. In the novella A River Runs Through It, an expert fisherman shares his thought process for recognizing a good fishing hole: “All there is to thinking is seeing something noticeable which makes you see something you weren’t noticing which makes you see something that isn’t even visible.”[3] Looking again and again until one sees the “something that isn’t even visible” is a recognition that the world is sacramental, a world of signs, permeated and ordered by Wisdom. Man comes to see that this world is a gift “destined for and addressed to man” (CCC 299). As anyone knows, the reception of a gift elicits first wonder and delight and then gratitude and praise as we lift our eyes from the gift to the giver. A sacramental view of the world moves man to lift his eyes to the Giver and, on behalf of the entire cosmos, to “offer all creation back to him” in a sacrifice of thanksgiving (CCC 358).[4]

Watered Garden

In the biblical account it is this worship that brings order; or rather, worship is the locus of right order. As a little world, man sums up all things, so when he entrusts himself into the hands of God, he gives everything. This gives his worship an inherently outward dimension—it includes more than himself. When man worships, everything worships, and so everything is consecrated. In the garden, rivers ran through it and out to the whole earth (Gn 2:10–14), making it a paradise in which the first Adam “played with childlike freedom.”[5] One can see here a created echo, a sort of natural catechesis, of Eternal Wisdom playing before the Father like a little child, “rejoicing before him always, rejoicing in his inhabited world” (Prv 8:30–31).

Penance as Devotion

“Dad, why does God like it when I suffer? I don’t like it.” This was the question that my five-year-old, Anastasia, posed during a recent dinner at home. As the liturgical seasons ebb and flow and certain penitential days make their appearance (not to mention the year-round meatless Fridays), my wife and I frequently encourage our three little children to offer some small, age-appropriate sacrifices to God. These exhortations, however, gave my little Anastasia the idea that God takes delight in our suffering—a long-debated question spanning multiple creeds. But is it true? If I put up with cold, or heat, or hunger, or that annoying co-worker, does God really find joy in my discomfort? What about people with cancer or any other painful illness? Ultimately, does God take delight in my death?

Children's Catechesis: Leading Children to Hear the Call of God

Recently, a local parish invited me to speak on a panel on vocations for middle and high schoolers. At most of these events, the questions usually include, “What is your day like?” “How often do you see your family?” and “What do you do for fun?” At this parish, the organizers left out a box for anonymous questions and didn’t screen them beforehand. Almost every question began with, “Why can’t I . . .” or “Why doesn’t the Church let me . . .” One of the monks on the panel leaned over and asked me, “Isn’t this supposed to be a vocations panel? Why are we even here?”

This experience opened my eyes to a reality: children and teenagers must know and love Jesus intimately as a person before anything we do to promote vocations will bear fruit. This intimacy is at the heart of all vocations, because at baptism God gives each person a share in his divine life, calling the Christian to a life of holiness. It’s within the context of a healthy family life that children first experience this love of God as well as the virtues and dispositions that serve as a remote preparation for their particular vocations.[1]

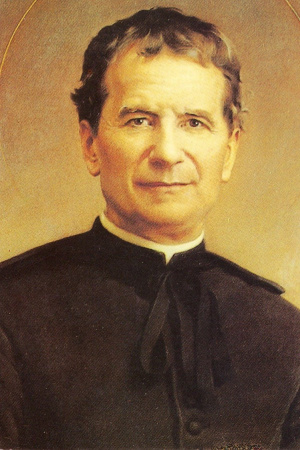

From the Shepherds — Learning From the Charism of St. John Bosco

In the Latin language there is a saying that could also be applied to our work as catechists: nomen est omen. This means that the name also reflects the inner essence of a person or a thing. In other words, the name speaks for itself. The name of St.

In the Latin language there is a saying that could also be applied to our work as catechists: nomen est omen. This means that the name also reflects the inner essence of a person or a thing. In other words, the name speaks for itself. The name of St.

Leading Eucharistic Revival in Schools, Homes, and Ministries

The two great commandments are to love the Lord with all your heart, mind, soul, and strength and to love your neighbor as yourself (see Mt 22:36–40). Catholic leaders are called to create and ensconce Catholic culture by striving to fulfill these two great commandments—and to guide the ministries that they lead to do the same. In my role as a high school vice president of faith and mission, I work alongside our principal and president to ensure that our school is a catalyst in the Eucharistic Revival and that the comprehensive operations of our school community serve these two commandments.

The first commandment calls Catholic leaders to prioritize facilitating first-generation encounters with Christ. To fulfill the second, we must foster a culture of evangelization in which we love our neighbor as ourselves and testify to Jesus’ kingship. Living out these commandments as Catholic leaders is especially exciting in this three-year sequence of Eucharistic Revival being guided by the United States Conference of Catholic Bishops. The USCCB is calling on leaders to create personal encounters with Jesus, reinvigorate devotion, deepen formation, and engage in missionary sending. What follows are reflections on how we are answering this call in our school community. I hope that it can serve as inspiration for other Catholic leaders during this time of Eucharistic Revival.

The Miracles of Jesus

One of the most characteristic features of Jesus’ earthly ministry was his performance of miracles, particularly healings and exorcisms.

One of the most characteristic features of Jesus’ earthly ministry was his performance of miracles, particularly healings and exorcisms.

Evangelization and Personal Freedom

If someone is married, in love, or has ever been in love, they can likely tell you when they knew they were in love and, more importantly, when they knew their significant other was in love with them. It’s also likely that one of the individuals fell in love first. Their heart had been moved and they had “arrived” to love. After having arrived, they had to do one of the hardest things: they had to wait. Why wait? Well, because love cannot be rushed, and it certainly cannot be forced. It must profoundly respect the freedom of the other because a love that is forced is no love at all—it is coercion. The human heart is only meant to open from within: to make a free choice to love.

Jesus spoke often about the heart of man. Speaking of the Pharisees he says, “This people honors me with their lips, but their heart is far from me” (Mt 15:8) and again, “But what comes out of the mouth proceeds from the heart and this defiles a man” (Mt 15:18). While for some it can seem like faith is nothing more than a list of doctrines and creeds, and conversion is nothing more than accepting “new teachings”; from the beginning, faith, conversion, and the work of bringing the Gospel to others, that is evangelization, have always been about the heart.

Evangelization, from the Catholic perspective, is “the carrying forth of the Good News to every sector of the human race so that by its strength it may enter into the hearts of men and renew the human race.”[1] From this definition, we can see that there are necessary aspects to authentic evangelization. First, there must be a proclamation of the Gospel. This speaks to the missionary mandate of the Church to bring the Good News to the whole world, not only in action but also in preaching and proclaiming. Scripture makes clear to us this mandate as we read Jesus’ final command, the last thing he spoke to his disciples before ascending into heaven. We call this final command the Great Commission, and we read one account of it in Matthew’s Gospel:

And Jesus came and said to them, “All authority in heaven and on earth has been given to me. Go therefore and make disciples of all nations, baptizing them in the name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Spirit, teaching them to observe all that I have commanded you; and behold, I am with you always, to the close of the age.” (Mt 28:18–20, emphasis added)

However, this “carrying forth of the Good News” is not an end in and of itself. Disciples of Christ do not proclaim the Gospel for the sake of its proclamation, just to speak the words. It is done to accomplish another end—namely, entering “into the hearts of men and renew[ing] the human race.” But we remember that the human heart must never be coerced, neither into love nor into belief. Instead, it must be approached with all its freedoms intact. This means that if reaching the human heart is the primary goal of authentic Catholic evangelization, then these efforts must always profoundly respect the other and his or her personal freedom. If this evangelistic atmosphere is not present, if proclaiming the Gospel is not being carried out in a way that profoundly respects the freedom of the other, then it is not authentic evangelization.

Lastly, we see that the strength by which this goal is achieved is not our own but belongs to the Gospel itself as we read, “so that by its strength it may enter into the hearts of men” (emphasis mine). When we evangelists remember that the Gospel has an intrinsic power, we experience freedom as well. We truly become “God’s fellow workers” (1 Cor 3:9), as Paul references in his letter to the Corinthians. Of course, we will aim to use every one of our God-given and developed gifts, but we will also make ourselves docile and open to the power of the Holy Spirit and the Gospel working through us. We will immerse ourselves in God’s Word, understanding that his Word contains power beyond any words of men. The freedom of the evangelist to become a vessel of God’s power through the Gospel message is necessary for authentic evangelization.