The Spiritual Life: Sacrifice – Path to Communion

Editor’s Note: The U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops has announced a three-year Eucharistic revival, to reawaken Catholics to the goodness, the beauty, and the truth of Jesus in the Eucharist. Each issue of the Catechetical Review, during the revival, will feature an article on the Eucharist, to empower our readers to make increasingly more meaningful contributions to the Eucharistic faith of those we teach. We hope you enjoy this article.

The great mystery of Christ’s sacrifice for us is at the heart of the Christian faith: “For Christ, our Paschal Lamb, has been sacrificed” (1 Cor 5:7). As the Catechism explains, Jesus’ death manifests his sacrifice in two ways:

Christ’s death is both the Paschal sacrifice that accomplishes the definitive redemption of men, through “the Lamb of God, who takes away the sin of the world,” and the sacrifice of the New Covenant, which restores man to communion with God by reconciling him to God through the “blood of the covenant, which was poured out for many for the forgiveness of sins.” (CCC 613)

Thus, the two principal effects of Christ’s sacrifice are, first, to remove our sins, and, second, to restore communion with God. Transformed by this gift of divine love, we are called to imitate Jesus and “walk in love, as Christ loved us and gave himself up for us, a fragrant offering and sacrifice to God” (Eph 5:2). Indeed, the Church teaches that every baptized Christian participates in Christ’s sacrifice (CCC 618). We are especially joined to it in the sacrament of the Eucharist, which makes Christ’s sacrifice ever present to us (CCC 1364). The Eucharist is a sacrifice because “it re-presents (makes present) the sacrifice of the cross, because it is its memorial and because it applies its fruit” to our lives by taking away our sins and restoring communion with God (CCC 1366).

The problem is that for most people today, the biblical notion of sacrifice seems obscure. What does sacrifice in general, and Christ’s sacrifice in particular, really mean? And how do the sacraments—especially Reconciliation and the Eucharist—manifest the Lord’s sacrifice?

The best way to gain insight into these questions is to consider the symbolism of the sacrifices in the Old Testament.

The Holy Samaritan Woman: Inspiration for the Spiritual Life of Catechists

Once on a hot summer day in France, I hiked a winding path with some companions all the way to the very source of a small stream. Having grown hot and tired from our hike, our local guides instructed us to rest a few moments and refresh ourselves at the spring. I hesitated as I watched the others drink confidently, even eagerly. The closest I had ever come to drinking untreated water was in sipping from the garden hose!

Their beckoning won me over, however, and I joined them. We drank the cold flowing water made all the more delicious by our thirst and the natural stone spicket. It occurred to me then that God intended water to be like that—pure, refreshing, a free gift of his goodness.

In the Gospel of John, Jesus promises that “living water” will well up in those who believe. The scene of Jesus and the Samaritan woman in John 4:1–42 is one those passages. This scene is particularly valuable for those who evangelize and catechize because it offers us a model of an authentic encounter with Jesus Christ and reveals to us the effects of that living water he promises.

In fact, we could almost name “the holy Samaritan”—as St. Teresa of Ávila calls her—our patron saint. We want to drink of the water Christ offers and teach others how to do the same, just as she did that day in Samaria.

The Spiritual Life: God, Who are You?

Have you ever wondered why Jesus’ disciples found it so difficult to grasp his true identity, even after living so closely with him and directly witnessing his great works?

Have you ever wondered why Jesus’ disciples found it so difficult to grasp his true identity, even after living so closely with him and directly witnessing his great works?

Jewish Oral Law and Catholic Sacred Tradition

I like to say that studying Judaism made me Catholic. Many years ago, I was a zealous, anti-Catholic evangelical Christian living in Jerusalem and active in the Messianic Jewish movement (the movement of Jews who believe in Jesus). Messianic believers are eager to rediscover the Jewish Jesus and the Jewish practices of the Early Church before it became tainted and compromised—so they say—with gentile beliefs and practices.

Like my Messianic Jewish friends, I accepted as the foundation of my faith the principle of sola scriptura—the great theological pillar of the Reformation positing that the Bible is our only and final source of authority in matters of faith. According to the Reformers and their followers, because human traditions are unreliable and prone to change, the Bible alone is the trustworthy Word of God that communicates to us the eternal truths that God revealed for our salvation (cf. 2 Tm 3:16).

Yet after spending a few years in the Messianic movement, I began to feel uneasy about sola scriptura. I found the doctrinal anarchy reigning in Protestantism and in Messianic Judaism increasingly disturbing. Even though all believers accepted the Bible as the Word of God, they constantly disagreed among themselves on substantial points of doctrine, with no final authority able to arbitrate between them. I began to think, moreover, that the endless multiplication of denominations found in Protestantism could surely not be God’s will. This led me to investigate what Scripture and Judaism had to say about the nature of God’s revelation to man.

The Domestic Church

How is the family a way to holiness? What does the Church mean when she calls the family the domestic church? A brief summary of the Scriptures and the development in how the term has been used will prove helpful.

How is the family a way to holiness? What does the Church mean when she calls the family the domestic church? A brief summary of the Scriptures and the development in how the term has been used will prove helpful.

Jesús y el transexualismo

En el número anterior de The Catechetical Review,[1] miramos la luz que da la Sagrada Escritura sobre el movimiento transgénero moderno, en particular los relatos de la Creación y de la Ley de Moisés. Ahora queremos ver específicamente algunos textos relevantes de los Evangelios y del Nuevo Testamento en general.

Las enseñanzas más claras de Jesús en cuanto a los asuntos sexuales se dan cuando los fariseos lo presionan sobre el divorcio en Mateo 19,3-6:

Y los fariseos lo pusieron a prueba,

“¿Es lícito al hombre divorciarse de su mujer por cualquier motivo? El respondió: ¿No han leído ustedes que el Creador, desde el principio, los hizo varón y mujer; y que dijo: ‘Por eso, el hombre dejará a su padre y a su madre para unirse a su mujer, y los dos no serán sino una sola carne’? De manera que ya no son dos, sino una sola carne. Que el hombre no separe lo que Dios ha unido.”

Jesús reconoce sólo dos géneros, masculino y femenino, y afirma que han sido creados por el mismo Dios. Además, Jesús afirma que la unión física / sexual entre hombre y mujer en el matrimonio es sagrada, habiendo sido establecida por Dios: “Que el hombre no separe lo que Dios ha unido”. ¿Cómo deriva esto desde Génesis 2,24, que describe a la unión de hombre y mujer utilizando la voz pasiva: “se une a su mujer… se hacen una sola carne”? Jesús interpreta esto de manera autoritativa como un pasivo divino, un recurso literario de la literatura bíblica y judía por el cual el escritor no nombra a Dios por reverencia religiosa, sino que pone en el pasivo a la acción de Dios. Por lo tanto, el significado verdadero de Génesis 2,24 es, “un hombre…es unido por Dios a su mujer… y los dos son hechos una sola carne por Dios”. En relación con la controversia moderna transgénero, por lo tanto, Jesús reconoce solamente dos géneros, e identifica a Dios – no a la sociedad, ni a una construcción social, ni a la psicología humana, etc. – como el Autor y Él que establece esos dos géneros, además de la institución del matrimonio.

La Ley judía, basada en la Ley de Moisés (Lev 18,1-23), rechazó a toda actividad sexual entre personas del mismo género, o entre personas en toda relación fuera del matrimonio entre un hombre y una mujer, y no existe la menor sugerencia que Jesús haya disputado esa enseñanza. Al contrario, Jesús avanza la enseñanza tradicional judía mucho más lejos, dándole una interiorización radical:

“Habéis oído que se dijo: ‘No cometerás adulterio.’ Pues yo os digo: Todo el que mira a una mujer deseándola, ya cometió adulterio con ella en su corazón. Si, pues, tu ojo derecho te es ocasión de pecado, sácatelo y arrójalo de ti; más te conviene que se pierda uno de tus miembros, que no que todo tu cuerpo sea arrojado a la gehena. Y si tu mano derecha te es ocasión de pecado, córtatela y arrójala de ti; más te conviene que se pierda uno de tus miembros, que no que todo tu cuerpo vaya a la gehena.” (Mateo 5, 27-30).

De acuerdo a la enseñanza de Jesús, entonces, las prohibiciones tradicionales de la inmoralidad sexual aplican también a actos interiores del corazón y de la imaginación. Tener fantasías acerca de actos malos ya de por sí es un acto malo, y el estándar ineludible de la santidad (“sed perfectos como es perfecto vuestro Padre celestial” Mateo 5,48) nos exige, si es necesario, tomar medidas radicales para evitar el pecado – lo cual se expresa de manera hiperbólica con “sácate el ojo” o “córtate la mano”.

Todo esto en realidad no deja espacio para que el discípulo de Cristo se imagine que él o ella tenga algún género distinto del de su sexo biológico. El sentimiento que uno sea de otro género distinto al de su sexo biológico quizás no sea algo que uno mismo elija, pero los discípulos de Cristo tienen que evaluar la verdad de sus sentimientos y sensaciones contra el estándar de la Revelación Divina y de la enseñanza de la Iglesia. La sensación de atracción erótica hacia su compañero de trabajo quizás tampoco sea elegida por uno mismo, y quizás sea “natural” en un sentido biológico. Sin embargo, no justifica que una persona casada actúe sobre esa sensación; más bien, el discipulado cristiano requiere que la persona casada reconozca ese sentido de atracción como un peligro que debe de ser rechazado y suprimido. Del mismo modo, una atracción física hacia un menor de edad quizás no sea algo que uno mismo haya elegido, y quizás sea “natural” biológicamente, sin embargo, el discipulado cristiano nos exige rechazar esos sentimientos y sensaciones, y ni sucumbir a ellos, ni actuar sobre ellos. Del mismo modo, el mero hecho de que tengamos sentimientos o sensaciones hacia el vestirnos, identificarnos o comportarnos de maneras asociados con el sexo opuesto, no justifica el consentir o actuar sobre esas sensaciones. Tenemos que actuar de acuerdo con lo que es verdad acerca de nuestros cuerpos y la verdad revelada en la Escritura.

Jesús enseñaba y llevó a cabo su ministerio entre el pueblo común de Judea a quienes les faltaba la riqueza y el tiempo libre como para consentir formas inusitadas o exóticas de comportamiento sexual. Sin embargo, San Pablo llevó el Evangelio a regiones de gran riqueza en el Imperio Romano, donde formas exóticas de actividad sexual extraconyugal eran comunes y populares. El emperador que condenó a muerte a Pedro y Pablo – Nerón – de hecho, practicaba una forma de transexualismo. Él y su amante de sexo masculino se vestían y se presentaban como jóvenes mujeres cuando mantenían relaciones sexuales juntos. Sin embargo, no era Roma, sino Corinto que tenía la mayor fama por el comportamiento sexual extravagante. El templo de Afrodita (alias Venus), la diosa del sexo, empleaba hasta mil prostitutas sagradas. No es coincidencia que las cartas de San Pablo a los corintos contengan su enseñanza más explícita sobre la sexualidad.

Jesus and Transgenderism

In the previous issue of The Catechetical Review,[1] we took a look at the light Scripture sheds on the modern transgender movement, especially the creation narratives and law of Moses. Now we wish to look specifically at relevant texts from the Gospels and New Testament generally.

Jesus’ clearest teachings on sexual matters arise when the Pharisees press him on divorce in Matthew 19:3-6:

"And Pharisees … tested him, “Is it lawful to divorce one’s wife for any cause?” He answered, “Have you not read that he who made them from the beginning made them male and female, and said, ‘For this reason a man shall leave his father and mother and be joined to his wife, and the two shall become one flesh? So, they are no longer two but one flesh. What therefore God has joined together, let not man put asunder."

Jesus only recognizes two sexes, male and female, and asserts that these have been created by God himself. Further, Jesus asserts that the physical/sexual union between man and wife in marriage is sacred, being established by God: “What God has joined together, let not man put asunder.” How does he derive this from Genesis 2:24, which describes the union of man and wife using the passive voice: “be united to his wife … the two shall become one flesh”? Jesus authoritatively interprets this as a divine passive, a literary device in biblical and Jewish literature in which the writer does not name God out of religious reverence, but phrases God’s action passively. Thus, the real meaning of Genesis 2:24 is, “a man … is joined by God to his wife … and the two are made one flesh by God.” In relation to modern transgender controversy, therefore, Jesus acknowledges only two sexes, and identifies God—not society, social construct, human psychology, etc.—as the author and establisher of those two sexes, as well as the institution of marriage.

Jewish law, based on the law of Moses (Lev 18:1-23), rejected sexual activity between persons of the same sex, or persons in any relationship outside of the husband-wife relationship, and there is not the slightest hint that Jesus disputed this teaching. On the contrary, Jesus pushes traditional Jewish teaching much farther, radically interiorizing it:

You have heard that it was said, “You shall not commit adultery.” But I say to you that everyone who looks at a woman lustfully has already committed adultery with her in his heart. If your right eye causes you to sin, pluck it out and throw it away; it is better that you lose one of your members than that your whole body be thrown into hell. And if your right hand causes you to sin, cut it off and throw it away; it is better that you lose one of your members than that your whole body go into hell. (Mt 5:27-30)

According to Jesus’ teaching, then, the traditional prohibitions of sexual immorality apply also to interior acts of the heart and the imagination. Fantasizing about evil acts is already itself an evil act, and the inescapable standard of holiness (“You must be perfect, even as your heavenly father is perfect” Mt 5:48) requires us, if necessary, to take radical measures to avoid sin—hyperbolically expressed as “plucking out the eye” or “cutting of the hand.”

All of this really leaves no room for the disciple of Christ to imagine that he or she is some other gender than his or her biological sex. The feeling that one is a different gender than one’s biological sex may not be self-chosen, but disciples of Christ have to evaluate the truth of their feelings and sensations against the standard of Divine Revelation and the Church’s teaching. The sensation of erotic attraction towards one’s co-worker may not be self-chosen and may in fact be “natural” in a biological sense. Nonetheless, it does not justify a married person acting on that sensation; rather, Christian discipleship requires the married person to recognize that sense of attraction as a danger that needs to be rejected and suppressed. Likewise, physical attraction toward a legal minor may not be self-chosen and may be biologically “natural”, but Christian discipleship requires us to reject those feelings and sensations, and neither indulge them nor act on them. In the same way, the mere fact that we have feelings or sensations toward dressing, identifying, or behaving in ways associated with the opposite sex, does not justify indulging and acting on those sensations. We have to act in accord with what is true about our bodies and the truth revealed in Scripture.

Jesus taught and ministered mostly among the common people of Judea who lacked the wealth and leisure to indulge in more unusual or exotic forms of sexual behavior. However, St. Paul brought the Gospel to areas of great wealth in the Roman Empire, where exotic forms of extramarital sexual activity were common and popular. The emperor who put Peter and Paul to death—Nero—did, in fact, practice a form of transgenderism. He and his male lover dressed and presented themselves as young women when engaging in sexual activity with each other. Yet it was not Rome but the city of Corinth that was most famed for extravagant sexual behavior. Corinth’s temple of Aphrodite (aka Venus), the goddess of sex, employed as many as a thousand sacred prostitutes. It is not coincidental that Paul’s letters to the Corinthians contain his most explicit teaching on sexuality.

The Bible and the Transgender Movement

We are living through a remarkable social revolution in the area of gender and sexuality, one that would have been very difficult to foresee thirty years ago. In the 1980’s, it was taken for granted that in athletic competitions, men competed with men and women with women. Various communist regimes at the time were under continuous suspicion of entering biological males into international or even Olympic women’s competitions. There was a universal consensus that this was unethical. Now, thirty or more years later, three female high school athletes in Connecticut have filed a federal discrimination complaint against the state’s interscholastic athletic association, which allows biological males who “identify” as females to compete in female athletic competitions. Unsurprisingly, these males are winning competitions and ousting female athletes from awards and scholarship opportunities.

What are we to make of these ideas that one can be a “woman” trapped in a man’s body, that one’s gender identity is fluid and not necessarily attached to one’s biological reality? Philosophy, psychology, biology, sociology, and other disciplines all have a contribution to make to this discussion; but in this article, I will be exploring what light the Scriptures have to shed on the issue.

The Goodness of Difference

“Let’s start at the very beginning, a very good place to start,” in the words of Maria von Trapp in The Sound of Music. Sexual difference is introduced into the biblical story line from the very first chapter. We read in Genesis 1:1-2: “In the beginning God created the heavens and the earth. The earth was without form and void, and darkness was upon the face of the deep; and the Spirit of God was moving over the face of the waters.” In Hebrew, the phrase translated “without form and void”, is tohu wabohu, a Hebrew phrase referring to a kind of chaotic state, where things are not distinguishable from one another, either through destruction or—in this case—because they have not yet been shaped. It is noteworthy that in what follows, God shapes the world typically by making distinctions and separating one thing from another. By doing so, different creatures and aspects of creation become identifiable. It is, after all, distinctions that create identity. If there are no distinctions between one thing and another, it is difficult to tell them apart, and if there were absolutely no distinctions, the two would necessarily be one and the same.

So, we read that God “separated the light from the darkness,” enabling both the light and the darkness to be identified, and then given the names of Day and Night.

Likewise, God makes a “firmament” to “separate the waters from the waters,” creating the sea, the sky, and the clouds. Later he makes the heavenly bodies to distinguish the passage of time, enabling the days, months, and years to be identified, and “separating the light from the darkness.” Finally, he makes man, and separates man into two sexes: “So God created man in his own image, in the image of God he created him; male and female he created them. And God blessed them, and God said to them, ‘Be fruitful and multiply …’” (Gen 1:27-28). Here we see that there is a certain unity between male and female in that both together make up “man” that is in the image of God. And yet there is a distinction between them too: they constitute a “them” in two parts. Finally, we see that the maleness and femaleness of man is directly related to the very first command God ever gives to humanity, “Be fruitful and multiply,” which can only happen when male and female unite as one. Many principles are entailed in these two verses: male and female are both good. They are integral to man’s imaging of God. Both are necessary for the fulfillment of the vocation that God has given humanity. The account of the creation of man concludes with the statement, “God saw everything that he had made, and behold, it was very good” (Gen 1:31). This includes the distinction between male and female, as well as all the other distinctions God has introduced into creation in order to create different identifiable creatures: the distinction between light and dark, day and night, sea and sky, one kind of animal from another kind, man from the animals, male from female. All these distinctions are good and given by God, not by creatures themselves. Yet, we see throughout the Bible that the forces of evil—and the Evil One—are intent on undoing the God-given distinctions and returning the world to an undifferentiated chaos. Evil rejects the goodness of distinctions God has introduced, starting with the most fundamental distinction—that between Creator and creature—but continuing down the line with the other distinctions as well.

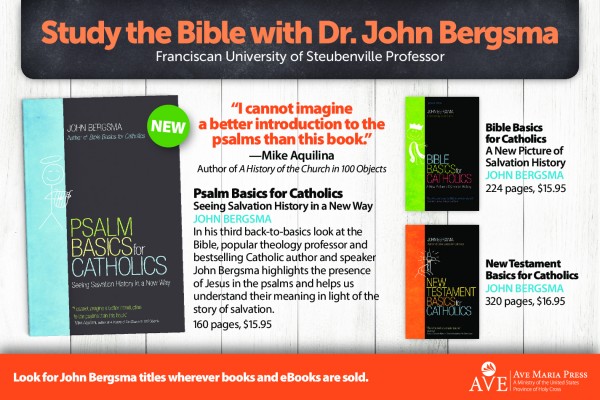

AD: New Bible Study by John Bergsma

This is a paid advertisment. To order these books or others from Ave Maria Press click here or call (800) 282-1865, ext. 1.

En el polvo del Rabino: Aclarando el discipulado para la formación de la fe en la actualidad

¿Será que el término “discipulado” es solo otro eslogan católico que se ha puesto de moda?

Aunque exista un mayor énfasis en el discipulado hoy en día, algunos dirigentes parroquiales admiten que no tienen una comprensión muy clara de lo que es exactamente el discipulado y cómo este tema pueda tener un impacto en el ministerio catequético. Incluso algunos se preguntan si no será otra tendencia pasajera. Así como me comentó un dirigente parroquial recientemente, “¿El discipulado?... Ah pues es una de esas palabras católicas que están de moda ahora…. Dentro de unos años, ya ni se dirá…. Así que voy a seguir haciendo lo que he estado haciendo.”

Parte del problema quizás sea que no se ha comunicado una visión consistente del discipulado. Las parroquias, apostolados o dirigentes diocesanos particulares a menudo inventan cada uno su visión sobre el discipulado. Pero, dada la importancia de este tema, imagínese si todos estuviéramos en la misma sintonía al ofrecer una visión del discipulado conformada de verdad por la Palabra de Dios. ¿Y si ofreciéramos a los dirigentes parroquiales un panorama más robusto del discipulado – uno que fuera fundamentado en el ministerio público de Jesús y enraizada en las enseñanzas de la Iglesia sobre la catequesis? Como veremos, esta emocionante visión bíblica del discipulado les equiparía a los trabajadores de la pastoral con un marco poderoso para la evangelización y la profundización de la relación que tiene el pueblo con Cristo.

El discipulado: su sentido bíblico

En el mundo del primer siglo en el que habitaba Jesús, ser discípulo se trataba de una sola palabra clave: imitación. Cuando un discípulo seguía a un rabino, el objetivo no era tan solo adquirir un dominio de las enseñanzas del rabino, sino también imitar su estilo de vida: la forma en que oraba, estudiaba, enseñaba, atendía a los pobres y vivía su relación con Dios cotidianamente. El mismo Jesús decía que cuando el discípulo esté plenamente formado, “será como su maestro” (Lc 6:40). Cuando San Pablo formaba a sus propios discípulos, les exhortaba que no recordaran solamente sus enseñanzas, sino que siguieran su forma de vivir: “Sed imitadores de mí, como también yo lo soy de Cristo” (1 Cor 11:1).

Aunque la palabra griega ‘discípulo’ (mathetés) significa ‘aprendiz’, el discipulado bíblico era algo muy distinto del aprendizaje que se da en el salón de clases hoy en día. En un campus universitario, lo más común es que el profesor dé clases a los estudiantes en una gran aula; los estudiantes toman apuntes, y más adelante durante el semestre se les hace un examen sobre lo que trataron las clases. Sin embargo, por lo regular no existe una relación personal continua, ni una convivencia entre el profesor y el estudiante en el ámbito universitario actual.

Seguir un rabino, no obstante, significaba vivir con el rabino, compartir los alimentos con él, orar con él, estudiar con él, y tomar parte en la vida diaria del rabino. La vida de un rabino debía de ser el ejemplo vivo de una persona conformada por la Palabra de Dios. Los discípulos, por lo tanto, estudiaban no solo el texto de la Sagrada Escritura, sino que también el “texto” de la vida del rabino.