The Spiritual Life: Sacrifice – Path to Communion

Editor’s Note: The U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops has announced a three-year Eucharistic revival, to reawaken Catholics to the goodness, the beauty, and the truth of Jesus in the Eucharist. Each issue of the Catechetical Review, during the revival, will feature an article on the Eucharist, to empower our readers to make increasingly more meaningful contributions to the Eucharistic faith of those we teach. We hope you enjoy this article.

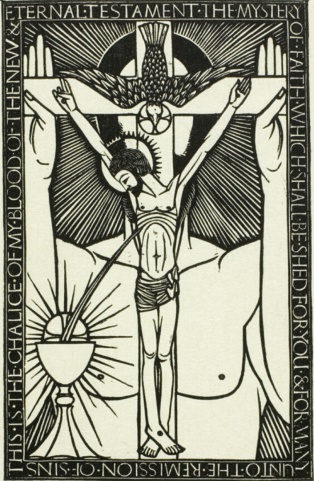

The great mystery of Christ’s sacrifice for us is at the heart of the Christian faith: “For Christ, our Paschal Lamb, has been sacrificed” (1 Cor 5:7). As the Catechism explains, Jesus’ death manifests his sacrifice in two ways:

Christ’s death is both the Paschal sacrifice that accomplishes the definitive redemption of men, through “the Lamb of God, who takes away the sin of the world,” and the sacrifice of the New Covenant, which restores man to communion with God by reconciling him to God through the “blood of the covenant, which was poured out for many for the forgiveness of sins.” (CCC 613)

Thus, the two principal effects of Christ’s sacrifice are, first, to remove our sins, and, second, to restore communion with God. Transformed by this gift of divine love, we are called to imitate Jesus and “walk in love, as Christ loved us and gave himself up for us, a fragrant offering and sacrifice to God” (Eph 5:2). Indeed, the Church teaches that every baptized Christian participates in Christ’s sacrifice (CCC 618). We are especially joined to it in the sacrament of the Eucharist, which makes Christ’s sacrifice ever present to us (CCC 1364). The Eucharist is a sacrifice because “it re-presents (makes present) the sacrifice of the cross, because it is its memorial and because it applies its fruit” to our lives by taking away our sins and restoring communion with God (CCC 1366).

The problem is that for most people today, the biblical notion of sacrifice seems obscure. What does sacrifice in general, and Christ’s sacrifice in particular, really mean? And how do the sacraments—especially Reconciliation and the Eucharist—manifest the Lord’s sacrifice?

The best way to gain insight into these questions is to consider the symbolism of the sacrifices in the Old Testament.

Principles for Celebrating the Liturgical Year

For Christians, the celebration of the mystery of Christ is, on the one hand, formative and, on the other, an opportunity to offer praise and thanksgiving. This is especially true for Catholics because the events of our salvation in Christ are recalled daily, weekly, seasonally, and annually. The awareness of the liturgical cycle may not be immediately evident to the average churchgoer. Even the topic of the “liturgical year” may well evoke a range of responses. Some will shrug shoulders in indifference; others will give a blank stare of confusion; still others may light up with enthusiasm. For catechists and religious educators, the organization of the Church’s liturgical seasons offers a fruitful way of contemplating the mysteries of our salvation and a powerful means of forming Christians in the fundamental values of our faith.

An Initial Principle and the Liturgical Calendar

A few principal ideas can help bring into focus what might otherwise seem a daunting task. The first is this: If you want to know what the Church believes, pay attention to what she says when she prays. In other words, the Church herself provides the key that allows access to the meaning of the liturgical year. This occurs concretely in a liturgical ritual celebrated on the Feast of the Epiphany. Sometimes called the Epiphany Proclamation, it is known officially as “The Announcement of Easter and the Moveable Feasts.” The texts and music for it can be found in Appendix I of the Roman Missal. Without reproducing the entire text here, a summary will suffice.

On the day of Epiphany, during which Christians celebrate the manifestation of Christ to the nations as the world’s redeemer (the liturgical context is significant), the liturgy makes an explicit link between Christmas and Easter: “As we have rejoiced at the Nativity of the Lord, so we also announce the joy of the Resurrection.” These are the two pivotal events of the liturgical year. The Announcement goes on to note the most significant celebrations, the dates of which change from year to year: Ash Wednesday, the beginning of the Lenten season, the date of Easter, the Ascension, Pentecost, Corpus Christi, and the First Sunday of Advent. A previous edition of the Missal provides additional commentary:

Through the rhythms of times and seasons let us celebrate the mysteries of salvation. Let us recall the year’s culmination, the Easter Triduum of the Lord: his last supper, his crucifixion, his burial and his rising.... Each Easter, as on each Sunday, the Holy Church makes present the great and saving deed by which Christ has forever conquered sin and death.... Likewise, the pilgrim Church proclaims the Passover of Christ in the feasts of the holy Mother of God, in the feasts of the Apostles and Saints, and in the commemoration of the faithful departed. To Jesus Christ, who was, who is, and who is to come, Lord of time and history, be endless praise, for ever and ever.[1]

The Church celebrates in time the great mysteries of human redemption. Careful attention to the rhythms of the liturgical calendar can help us to honor the sacrality of time and notice how God works our salvation through the different seasons.

A first point that emerges from this liturgical proclamation can be seen in the structure of the calendar. The Paschal Mystery (Easter) is central to everything Christians do, central to the way we live. That conviction is made visible, sensible, in the unfolding of the liturgical year with each season’s emphasis on one aspect or other of the mystery of salvation. A second, no less important, point is that every Sunday is a remembrance of the Lord’s Day, the Resurrection. The richness of Sunday is beautifully developed by Pope St. John Paul II’s 1998 Apostolic Letter Dies Domini (On Keeping the Lord’s Day Holy), in which he reflects on five aspects of the first day of the week.[2] A familiarity with these can be a tremendous source for an educator’s reflection on the liturgy.

Advent at Home: Five Practices for Entering into the Season

Most Catholic parents are so far removed from a rich Catholic culture that living a liturgical season—let alone the liturgical year—can seem impossible.

Most Catholic parents are so far removed from a rich Catholic culture that living a liturgical season—let alone the liturgical year—can seem impossible.

Editor’s Reflections: The Liturgical Life – A Source of Healing

“The kingdom of heaven may be likened to a man who sowed good seed in his field. While everyone was asleep his enemy came and sowed weeds all through the wheat, and then went off” (Mt 13:24–25).

“The kingdom of heaven may be likened to a man who sowed good seed in his field. While everyone was asleep his enemy came and sowed weeds all through the wheat, and then went off” (Mt 13:24–25).

Our Lord’s imagery helps us make sense of difficult and painful situations existing within the Church. He is describing, afterall, the “kingdom of God.” If I’m honest with myself, I’m aware that there are weeds also growing in my heart. St. Paul understands the dramatic situation within the Christian, lamenting that “I do not do the good I want” (Rm 7:19). This is an apt description of the disciples of Jesus, called as we are to align our ways of thinking and living more closely to those of Christ the Teacher, a movement only possible when we cooperate with grace.

St. John Paul II described the greatest temptation we lay people face: the tendency to separate faith from life.[1] Of course, it’s quite clear that every baptized person faces this struggle. We can be too at ease, too comfortable, with both wheat and weeds existing in the heart. The problem, of course, explained in the immediately preceding parable in Matthew’s Gospel is this: weeds can have thorns, and thorns can choke, cause severe damage, and obstruct fruitfulness.

This drama is particularly vivid for anyone who teaches the faith. We can be so close to the Mystery of Christ, teaching it as we do, that we can tend to not remain before it in our own spiritual life. It can lose its power to confront and challenge us. Familiarity can breed passivity.

Viaticum: Sacred Food for the Final Journey

We never know which Holy Communion might be our last. We make a big deal of our First Communion, and rightly so. But why don’t we have a strong catechesis and spirituality of Viaticum, that final time we receive the Body of Christ before our soul leaves our own body to meet him?

As a Church, perhaps we are missing a robust eucharistic spirituality in general. Maybe we lack a proper sober focus on our preparation for death. We could likely all benefit from considering the Last Rites in a more personal and specific way, so that they may be more fruitfully celebrated for us and those we love.

For the Dying

“Father, you got here just in time,” the nurse says. It is such a blessed and needed relief when someone receives their final sacraments! No matter the circumstances, these gifts of Holy Mother Church provide occasions of intense grace, whether the person was a daily communicant or long fallen away, whether in an emergency situation or with the comfort of hospice care. Often people will seem to cling to life, whether consciously or not, and then decline rapidly after a priest’s visit. In my experience, this is particularly true if Confession was needed. Care should always be taken to arrange a private moment for that purpose to be properly disposed in the state of grace before the reception of the Eucharist.

Too often, the effects of medicine and the progression of illness limit the scope of the recipient’s participation. Especially with privacy law restrictions ever increasing, the faithful should be reminded to notify the parish with members’ serious health updates so they can be taken care of promptly. Our spiritual family has special solidarity with the suffering.

The texts of the ritual are of incomparable theological, poetic, and pastoral value. The Commendation of the Dying stands out among them with its litanies. Only in the most dire situations should these prayers be omitted. There is a unique form for the administration of Viaticum: “May the Lord Jesus Christ protect you and lead you to eternal life.” All this serves to heighten the gravity of this liturgical and human reality.

Receiving the Anointing of the Sick and Apostolic Pardon together with Viaticum is a sign of divine election. That monumental last blessing has sadly become a forgotten treasure of our spiritual patrimony. What certain peace a soul feels to experience the full force of the Church’s forgiving authority with a plenary indulgence to remit all temporal punishment due to sin in Purgatory, just when it is needed the most! The text is worth quoting in full: “Through the holy mysteries of our redemption may almighty God release you from all punishments in this life and in the life to come. May He open to you the gates of paradise and welcome you to everlasting joy. By the authority which the Apostolic See has given me, I grant you a full pardon and the remission of all your sins in the name of the Father, and of the Son, and of the Holy Spirit.”

Inspired Through Art: Mass of St. Gregory by Diego de la Cruz c. 1490

The Mass of St. Gregory depicts a miracle in the life of Pope St. Gregory the Great, who died in Rome on March 12 of AD 604. According to tradition, he and others experienced the appearance of Jesus as the pope celebrated a particular Mass. It is considered a eucharistic miracle because of the circumstances surrounding the event.

We learn of this narrative through the stories of the saints collected and published by Jacobus de Voragine, a Dominican priest of the thirteenth century. The original title of his book was Readings from the Saints. But over time, the published work attained the title The Golden Legend. His collection was gathered from wide-ranging sources and traditions and underwent many revisions and additions after his lifetime. The stories are not canonical, so we are not obligated to believe the accuracy of the events depicted. But we find many of the narratives are part of our Catholic devotional love of the saints—they are tales that have been in the minds and hearts of Catholics for centuries. We can read of St. Helen finding the True Cross; the story of St. George and the Dragon; the lives of Mary’s mother and father, Anna and Joachim—it is a very long list. On the matter of belief in apocryphal texts, I prefer to offer Fr. Benedict Groeschel’s usual rejoinder to those who disbelieve in miracles: how do you know . . . were you there?

It is possible to find translations of early versions of The Golden Legend that are substantially the “original” form without the addition of later authors, which may give some confidence to those seeking Jacobus de Voragine’s personal contribution to the collection.

The translation of the original version of the St. Gregory narrative describes the story in this way:

A certain woman used to bring altar breads to Gregory every Sunday morning, and one Sunday when the time came for receiving Communion and he held out the Body of the Lord to her, saying: “May the Body of Our Lord Jesus Christ benefit you unto life everlasting,” she laughed as if at a joke. He immediately drew back his hand from her mouth and laid the consecrated Host on the altar, and then, before the whole assembly, asked her why she had dared to laugh: “Because you called this bread, which I made with my own hands, the Body of the Lord.” Then Gregory, faced with the woman’s lack of belief, prostrated himself in prayer, and when he rose, he found the particle of bread changed into flesh in the shape of a finger. Seeing this, the woman recovered her faith. Then he prayed again, saw the flesh return to the form of bread, and he gave Communion to the woman.[1]

Why Beauty Matters for Catechesis and Catholic Schools

In modern culture, relativism reigns supreme. Consequently, the transcendentals of truth, goodness, and beauty no longer seem to transcend beyond the subjective whims of every autonomous individual self. Truth is a matter of one’s opinion. Goodness is relative to each person. Beauty is a matter of personal preference.

Catechists and Catholic educators have been given a great opportunity to lead the young people entrusted to their care to encounter objective truth, consistent moral laws that lead to the flourishing of goodness, and to appreciate authentic beauty. Although the three transcendentals are inseparable, I would like to focus on the role of beauty in teaching, evangelization, and formation.

Bishop Robert Barron frequently exhorts the faithful to “lead with beauty.” Images are powerful means of conveying both the truth and distortions of the truth. Images have been used well to market products and lead people astray into ideology. The Church has employed the use of sacred art to convey the truth in a powerful and formative way. In the introduction to the Compendium of the Catechism of the Catholic Church, then-Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger explains the rationale for using sacred images within the Compendium:

Images are also a preaching of the Gospel. Artists in every age have offered the principal facts of the mystery of salvation to the contemplation and wonder of believers by presenting them in the splendor of color and in the perfection of beauty. It is an indication of how today more than ever, in a culture of images, a sacred image can express much more than what can be said in words, and be an extremely effective and dynamic way of communicating the Gospel message.[1]

The beauty within art, architecture, music, and film is a visible manifestation of a truth being communicated by the artist. Beauty, when used well, can lead the faithful to encounter the face of Christ the Incarnate Word.

In order to renew catechesis and Catholic schools with beauty, first we must discuss the definition and nature of beauty. Second, we need to examine what role beauty plays in our lectures, presentations, and classrooms. Finally, we must work toward greater manifestations of beauty within the liturgy.

The Spiritual Life: How the Eucharist Catechizes about the Meaning of Life

The United States Conference of Catholic Bishops is currently undertaking a Eucharistic revival.

The United States Conference of Catholic Bishops is currently undertaking a Eucharistic revival.

Editor's Reflections: Toward a Eucharistic Revival

The Feast of Corpus Christi last month was a momentous event in the life of the Church in the United States. The celebration of this liturgy begins a Eucharistic revival, a period of historic importance that will culminate in a National Eucharistic Congress in Indianapolis in the summer of 2024.

The Feast of Corpus Christi last month was a momentous event in the life of the Church in the United States. The celebration of this liturgy begins a Eucharistic revival, a period of historic importance that will culminate in a National Eucharistic Congress in Indianapolis in the summer of 2024.

AD: Come, Follow Me Bi-lingual Training Conference, June 10-11, Nashville

Click here to register for this bi-lingual training in the Come, Follow Me method of catechesis.