Curriculum from a Catholic Worldview

We can take for granted the fact that the Catholic Church runs a large number of schools throughout the world. It is clear that the Church must offer religious education, but why does the Church teach math, gym class, science, literature, and history? Wouldn’t it just be easier if the Church focused more narrowly on the supernatural; why also teach about the material world and how to read and write? In the Great Commission, Jesus commanded his apostles to make disciples, (mathetes in Greek and discipli in Latin – both words for students) and to teach them (Mt 28:19-20). Jesus, the Word of God, by whom the universe was made, established a Church that from the beginning embraced instruction on the nature of reality as a whole.

The Liberal Arts and a Catholic Worldview

The Church embraced the liberal arts in order to help its members, especially religious, to understand and contemplate the Word of God, as well as to speak and write effectively to share this knowledge. From the teaching of the seven liberal arts at the cathedral and monasteries schools, the universities formed to teach philosophy and three terminal degrees in theology, law, and medicine. The Church’s mission of salvation grew to include the complete formation of the person, uniting faith and reason in the common mission of seeking how to live in the world and order all things to the glory of God.

Catholic education, drawing upon both the natural and supernatural, offers a complete vision of life: a Catholic worldview. Worldview, in a simple sense, describes the way in which we see reality and form our students to understand it and live within it. Teaching with a robust Catholic vision embraces the entire person: body, emotions, mind, and will. The human person, as a sacramental being (body-soul unity), requires development of its potential in all of its dimensions: strength and health of body; control of the emotions in accord with the good; conformity of the mind to reality and development of the mental habits that enable one to understand and express oneself clearly; the development of the virtues of will that lead to happiness; and the encounter with the living God that enlivens our soul and enables a life of holiness.

The Catholic school cannot simply offer the same instruction as a public education, with religious education and the Mass superadded onto the curriculum. Every subject must be taught in a distinctive fashion that reflects the unity of knowledge, having a common source in God—his creation and revelation—and ordered in a wisdom that communicates the ultimate purpose of all things. A Catholic school approaches every subject through the two wings of faith and reason, knowing that every truth conforms our minds to the mind of God. Simone Weil claims that every truth “is the image of something precious. Being a little fragment of particular truth, it is a pure image of the unique, eternal and living Truth which once in a human voice declared ‘I am the Truth.’ Every school exercise thought of in this way, is like a sacrament.”[1]

AD: A Riveting Analysis of the Western Culture Crisis

This is a paid advertisement in the October-December 2019 issue.

The Bible and the Transgender Movement

We are living through a remarkable social revolution in the area of gender and sexuality, one that would have been very difficult to foresee thirty years ago. In the 1980’s, it was taken for granted that in athletic competitions, men competed with men and women with women. Various communist regimes at the time were under continuous suspicion of entering biological males into international or even Olympic women’s competitions. There was a universal consensus that this was unethical. Now, thirty or more years later, three female high school athletes in Connecticut have filed a federal discrimination complaint against the state’s interscholastic athletic association, which allows biological males who “identify” as females to compete in female athletic competitions. Unsurprisingly, these males are winning competitions and ousting female athletes from awards and scholarship opportunities.

What are we to make of these ideas that one can be a “woman” trapped in a man’s body, that one’s gender identity is fluid and not necessarily attached to one’s biological reality? Philosophy, psychology, biology, sociology, and other disciplines all have a contribution to make to this discussion; but in this article, I will be exploring what light the Scriptures have to shed on the issue.

The Goodness of Difference

“Let’s start at the very beginning, a very good place to start,” in the words of Maria von Trapp in The Sound of Music. Sexual difference is introduced into the biblical story line from the very first chapter. We read in Genesis 1:1-2: “In the beginning God created the heavens and the earth. The earth was without form and void, and darkness was upon the face of the deep; and the Spirit of God was moving over the face of the waters.” In Hebrew, the phrase translated “without form and void”, is tohu wabohu, a Hebrew phrase referring to a kind of chaotic state, where things are not distinguishable from one another, either through destruction or—in this case—because they have not yet been shaped. It is noteworthy that in what follows, God shapes the world typically by making distinctions and separating one thing from another. By doing so, different creatures and aspects of creation become identifiable. It is, after all, distinctions that create identity. If there are no distinctions between one thing and another, it is difficult to tell them apart, and if there were absolutely no distinctions, the two would necessarily be one and the same.

So, we read that God “separated the light from the darkness,” enabling both the light and the darkness to be identified, and then given the names of Day and Night.

Likewise, God makes a “firmament” to “separate the waters from the waters,” creating the sea, the sky, and the clouds. Later he makes the heavenly bodies to distinguish the passage of time, enabling the days, months, and years to be identified, and “separating the light from the darkness.” Finally, he makes man, and separates man into two sexes: “So God created man in his own image, in the image of God he created him; male and female he created them. And God blessed them, and God said to them, ‘Be fruitful and multiply …’” (Gen 1:27-28). Here we see that there is a certain unity between male and female in that both together make up “man” that is in the image of God. And yet there is a distinction between them too: they constitute a “them” in two parts. Finally, we see that the maleness and femaleness of man is directly related to the very first command God ever gives to humanity, “Be fruitful and multiply,” which can only happen when male and female unite as one. Many principles are entailed in these two verses: male and female are both good. They are integral to man’s imaging of God. Both are necessary for the fulfillment of the vocation that God has given humanity. The account of the creation of man concludes with the statement, “God saw everything that he had made, and behold, it was very good” (Gen 1:31). This includes the distinction between male and female, as well as all the other distinctions God has introduced into creation in order to create different identifiable creatures: the distinction between light and dark, day and night, sea and sky, one kind of animal from another kind, man from the animals, male from female. All these distinctions are good and given by God, not by creatures themselves. Yet, we see throughout the Bible that the forces of evil—and the Evil One—are intent on undoing the God-given distinctions and returning the world to an undifferentiated chaos. Evil rejects the goodness of distinctions God has introduced, starting with the most fundamental distinction—that between Creator and creature—but continuing down the line with the other distinctions as well.

Christus Vivit: A New Vision of Youth and Young Adult Ministry

On March 25th, Pope Francis released Christus Vivit, “Christ is alive!” This post-synodal exhortation is addressed both to young people (16 to 30 year-olds) and the entire Church. Rich with inspirational quotes and practical suggestions, the document contains many insights about youth, for youth, and for those who minister to youth, while raising many important questions that need to be addressed.

About Youth

A young person stands on two feet as adults do, but unlike adults, whose feet are parallel, he always has one foot forward, ready to set out, to spring ahead. Always racing onward. (140)

Pope Francis begins the document by highlighting young people in the Bible as well as in Church history, figures such as Joseph (son of Jacob), Ruth, and David to St. Sebastian, St. Francis of Assisi and St.

Thérèse of Liseiux. Young people have always played an important role in salvation history. Particular attention is given to Mary, who as a young woman said “yes” to Gabriel, and to Jesus himself: “It is important to recognize that Jesus was a young person. He gave his life when he was, in today’s terms, a young adult” (23).

“Youth is more than simply a period of time; it is a state of mind” (34). This is why the Church, over two thousand years old, can be considered “young”—and needs the help of young people to keep her that way. Francis compares the shallow and superficial ways culture can manipulate youth to the true happiness that only Christ can offer. “Dear young friends, do not let them exploit your youth to promote a shallow life that confuses beauty with appearances” (183). Young people are in danger of being isolated and exploited which makes relationships with older people a great benefit. The young generation needs older generations, and the older generations need them. “When young and old alike are open to the Holy Spirit, they make a wonderful combination” (192).

La formación en la fe para adultos en la comunidad hispana católica en los Estados Unidos: una reflexión

“La evangelización es la misión fundamental de la Iglesia. Es también un proceso continuo de encuentro con Cristo, un proceso que los católicos hispanos han hecho muy suyo en su planeación pastoral. Este proceso genera una mística (teología mística) y una espiritualidad que conduce a la conversión, comunión y solidaridad, tocando cada dimensión de la vida cristiana y transformando cada situación humana.”[1]

Adult Faith Formation in the Hispanic Catholic Community in the United States: A Reflection

“Evangelization is the fundamental mission of the Church. It is also an ongoing process of encountering Christ, a process that Hispanic Catholics have taken to heart in their pastoral planning. This process generates a mística (mystical theology) and a spirituality that lead to conversion, communion, and solidarity, touching every dimension of Christian life and transforming every human situation.”[1]

On the occasion of this important milestone marking the publication of the USCCB’s seminal document on adult faith formation, Our Hearts Were Burning Within Us (hereafter “the document”), issued on the cusp of the new millennium, it is worth reflecting on its impact and influence on Hispanic ministry in this country. Much has taken place since that time, while significant ongoing challenges remain.

Some Pertinent Principles

Although the document does not explicitly address the Hispanic or other specific cultural communities, a number of its organizing principles do speak to some noteworthy realities. These principles will be the touchstones for this reflection. First, persons will always prefer to worship where they feel comfortable and at home. Second, faith as it relates to the family is a critical factor in any religious tradition. And lastly, social customs and popular devotion in harmony with the Gospel are to be respected, affirmed, and celebrated.

First Things First - Welcoming and Hospitality

While data are generally lacking regarding the number of Hispanics who have left the Catholic Church, current information suggests that a significant number of Hispanics who were baptized as Catholics join other Christian denominations and religious traditions every year; including fundamentalist groups and “storefront” churches—many of which maintain Hispanic cultural traditions that might otherwise be considered to be “Catholic,” including quinceañeras (fifteenth birthday blessings) and Epiphany celebrations. New arrivals often find the structure of the parish and the style of worship to be very different from what they experienced in their native country. In this unfamiliar environment, they are frequently targeted for what could be considered aggressive proselytizing by non-Catholic groups, and are offered transportation, many kinds of assistance, skillful scriptural preaching, as well as a friendly community to which to belong.

All this highlights the compelling need for Catholic parishes to provide a welcoming and hospitable atmosphere to newcomers, including Spanish-language and/or bilingual worship, ministries, parish pastoral leaders, and personnel whenever possible. In addition, Catholic parishes must be aware of several factors that can make Hispanics feel unwelcomed in the Catholic Church and make them more open to seeking a home in other faith traditions. Among these factors are: an unspoken attitude from parish staff or parishioners that they are “undesirable”; excessive or overwhelming administrative rules and forms; and being required to produce evidence of contribution envelopes before they can receive the sacraments.[2]

Youth & YA Ministry: Modern Man Listens More to Witnesses than to Tweeters

Head buried in her screen, she was more concerned with live-tweeting the event than listening to the speaker. She was so busy scrolling through social media, she didn’t realize she had walked past a friend she hadn’t seen in years.

Head buried in her screen, she was more concerned with live-tweeting the event than listening to the speaker. She was so busy scrolling through social media, she didn’t realize she had walked past a friend she hadn’t seen in years.

AD: How to Share & Live the Faith with Others

This is a paid advertisement in the January-March 2019 issue. Advertisements should not be viewed as endorsements from the publisher.

Changing the Culture

I grew up in a relatively large Catholic family who never missed Sunday Mass. I was sent to Catholic elementary and high schools, where school Masses were celebrated with regularity. I also had what I now believe to be a special grace of faith from the Lord, where I never questioned the existence of God or Church teaching (as I understood it to be at the time)—even though by young adulthood many of those around me were questioning both. I also was a faithful altar-server straight up until college, serving at many Masses during the school year. Considering the trajectory of my life, I had received Communion nearly one thousand times by the time I went away to college.

But in reality, the effects that receiving my Lord in communion had on me were minimal. I went to Mass faithfully, and I even went prayerfully, but I was not coming away changed by the encounter in any visible way. While I had a personal faith in God, I was lacking in a personal understanding of what it meant to give my life to him, to desire to live a new life in Christ, and ultimately, to have this change of life flow from personal repentance and conversion. Sherry Weddell points out that any of these four obstacles “can block the ultimate fruitfulness of valid sacraments,”[1] and I was missing three out of four.

This stymied the flow of sacramental grace in my life. It would do the Lord a disservice to say that I had no spiritual benefit at all: I was going to Mass weekly, doing so in a spirit of faith, and offering sincere prayers during the liturgy. All the same, I can say with certainty that the spiritual effects of Communion for me were minimal. In terms of grace, I was collecting a dime each week at best, but the Lord had been offering me a dollar. And a central reason that I benefited so little was precisely because I had attended Mass in my parish so often.

Counterintuitive as that might sound, it’s true. This was because in my culturally Catholic parish, no one had ever modeled for me in my Catholic schooling or in my parish a discipled life flowing from the Eucharist, complete with active and visible spiritual fruit. Regularly observing and participating in a parish culture of churchgoing Catholics taught me to expect little transformation from receiving communion (either personally or in the community), and so I never did. Participation was the clear focus, not fruitfulness. Therefore, any catechesis on the Real Presence I received in a classroom setting was always obstructed by what my experience was teaching me—namely, that receiving the Lord in Communion was not meant to result in immediate spiritual fruit that could be visibly perceived in the community.

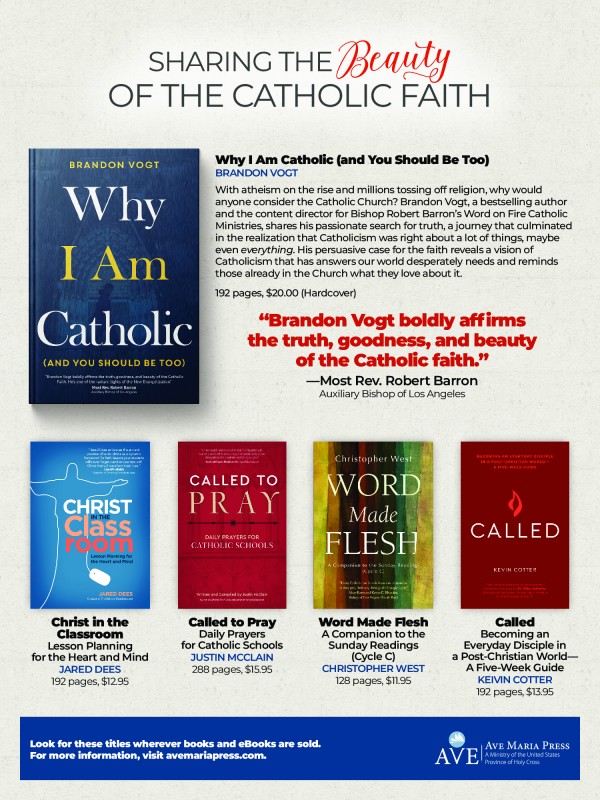

AD: Ave Maria Press—Sharing the Beauty of the Catholic Faith

This is a paid advertisment. For more from Ave Maria Press click here or call (800) 282-1865, ext. 1.