Youth & Young Adult Ministry: Blessed Stanley Rother—Model of Perseverance

On September 23, 2017, the Catholic Church celebrated the beatification of a farm boy from Oklahoma. Thirty-two years earlier, in a small town in Guatemala, “Padre Apla’s” was martyred in his rectory in the middle of the night.

Stanley Rother was born in 1935 in Okarche, Oklahoma. His bucolic family was very faithful and prayed a Rosary every night after dinner, kneeling at the table. Unbeknownst to his family, Stanley contemplated a call to the priesthood while he rode the tractor in the field. In 1953, he went to seminary in San Antonio. There he worked in the seminary’s bindery and built a shrine to the Blessed Virgin Mary. Feeling more at ease working outside than in the classroom, he struggled with the academics in seminary and wrote in his journal, “Am thinking about another vocation,” later adding that his director, “set me straight on another vocation.”[1]

...

After returning to Oklahoma City, Stanley met with the director of vocations and with his bishop. Nothing is recorded of that meeting except a single mention in Rother’s journal: “Saw Bishop and he will send me on next fall.”[3] Whatever happened, Stanley convinced the bishop of his calling and was admitted to another seminary. He was ordained a priest in 1963. Five years later, he was sent to the diocesan mission in Guatemala and flourished as a pastor, learning to speak Tz’utujil (the local language) and even aiding in the translation of the New Testament into that language.

God knew what he was doing with this Oklahoma farm boy. Having learned about crops, irrigation, and proper planting practices on his family farm, Stanley put his knowledge to use by helping the Tz’utujil people better their farming techniques. He knew the value of hard work and was frequently seen eating and working alongside his parishioners. Decades before Pope Francis called for priests to “smell like their sheep,” Fr. Rother was working side by side with the men and women God gave him to shepherd.

Catholic Education—A Road Map: The Work of Sofia Cavalletti, Catechesis of the Good Shepherd

Sofia Cavalletti was arguably the most effective catechetical theorist and practitioner of her era. Born in 1917, she belonged to a noble Roman family, who had served in the papal government. Marchese Francesco Cavalletti had been the last senator for Rome in the papal government, prior to its takeover in 1870 by the Italian state. Sofia herself bore the hereditary title of Marchesa, and lived in her family's ancestral home in the Via Degli Orsini. In 1946, the young Sofia Cavalletti began her studies as a Scripture scholar at La Sapienza University with specializations in the Hebrew and Syriac languages. Her instructor was Eugenio Zolli, who had been the chief rabbi of Rome, prior to and during World War II and who had become a Catholic after the war. Following her graduation, Cavalletti remained a professional academic for the whole of her professional career.

Cavalletti's involvement with catechetics came about by chance, in 1952, after she was asked to prepare a child for his first communion. Soon after this experience, Cavalletti began collaborating with Gianna Gobbi, a professor of Montessori education. Together, they developed what came to be known as the Catechesis of the Good Shepherd, painstakingly creating materials that would serve the religious needs of children from the ages of three to twelve years. Taking the Montessori sensitive periods as a starting point and guided by the response of real children as the “reality check,” Cavalletti refined her understanding of the religious experiences that children were likely to respond to at each stage of their development. She would create materials and make them available to the children. If the material was not used, she determined that it had not met the mark and she would dispose of it, irrespective of how much effort she had put into it.

Very early in her work, Cavalletti discerned the central role of “wonder” in a child’s religious development and she realized that for young children (and indeed for every human being), wonder is evoked by “an attentive gaze at reality.”[i] Consequently, young children were encouraged to begin their relationship with God by recognizing, one by one, the gifts offered to them in the created world. To meet this need, the Montessori “practical life” works were found to be ideal. Children were given tasks such as flower arranging, slow dusting, leaf washing and the like. The experience of Montessori classrooms for over a hundred years has born witness to the effectiveness of this approach. Engagement with concrete “hands on” activities seem to be the basis not only of religious development but for learning of any kind.

The careful observation of the needs of real children by Montessori had identified the basic stages of learning, (outlined in my previous article). Cavalletti summed this up in a simple axiom: first the body, then the heart, then the mind. As the twentieth century progressed, she evaluated new ideas in education, Biblical scholarship, and theology. Cavalletti did not easily fall prey to a widely reported educational phenomenon, the “band wagon effect.” She was an “action researcher” who allowed herself to be guided by the reactions of the children she was working with. If a learning material failed to engage the children, it was discarded and alternatives sought.

One of the most striking and commonly reported phenomena of the Catechesis of the Good Shepherd is that children seem to be able to arrive at profound theological understandings for themselves—without being told.

Tailored Accountability: The Art of Pastoral Accompaniment

This article opens with stories of Jan Tyranowski and Karol Wojtyla, Saints Ignatius, Peter Faber and Francis Xavier to supply us with a picture of the value of real pastoral accompaniment, wherein a more personally directed style of formation takes place, either alongside traditional classroom catechesis, or, for a season at least, instead of the classroom lecture style of formation. Pastoral accompaniment, whether formal or informal, takes place when a spiritually experienced mentor walks with a less-experienced disciple through the steps of gaining maturity. It could be called a type of spiritual life-coaching. In recent years, the Holy Spirit has been calling for a renewal of pastoral accompaniment in the Church. Pastoral accompaniment is not the same as spiritual direction, although there are similarities and overlaps. The term “spiritual friendship” or “spiritual mentoring” might be more apt to convey the sense of what the Spirit seems to be inviting the Church to develop. Accompaniment happens when one who has been practicing the spiritual life with some intentionality advises another who wants to grow in the spiritual life.

AD: Pauline Books & Media—Books on Discernment, Saints and more

This is a paid advertisement in the July-September 2018 issue. Advertisements should not be viewed as endorsements from the publisher. To find out more about products from Pauline Books & Media call 800-878-4463 or visit www.PaulineStore.org

AD: Powerful Movies on Great Saints

This is a paid advertisement. To view the lives of the saints movies from Ignatius Press, click here or call 800-651-1531 to order.

St. John Vianney – A Saint of the New Evangelization, Part 3: The Holiness of the Catechist

In this final installment, we reflect on the most essential characteristic of an effective catechist for the new evangelization: allowing Christ to transform us through holiness of life. Among all of the words spoken during the pontificate of Blessed Paul VI, there is one phrase most often repeated today that came to prominence in one of his last letters, Evangelli Nuntiandi. It was his observation that “modern man listens more willingly to witnesses than to teachers, and if he does listen to teachers, it is because they are witnesses” (41).

Editor's Reflections: John Paul II and Redemptive Suffering

Seventeen years ago this May, I had the extraordinary blessing of meeting one of my heroes: Pope St. John Paul II. I did not meet the young pope who had once famously escaped the Vatican in disguise to enjoy a day of skiing. Rather, this was the much older man whose body was being ravaged by Parkinson’s Disease. As I stood in line inching forward to meet him, I noticed the muscles in his face were so weakened that saliva was pooling by his feet.

The Spiritual Life: Saint Elizabeth of the Trinity and Contemplative Prayer, Part 2

Adoration: Losing Self, Finding Peace

This article is the second in a three part series on the spiritual mission of St. Elizabeth of the Trinity for our time. We are arguing that contemplation of the Triune God can heal the wounds of social alienation that so profoundly mark the experience of believers today and, more than this, offers a fullness of Christian living no other kind of prayer can match. In our last article, we distinguished St. Elizabeth’s confidence in presenting a contemplative approach to the Trinity in contradistinction to the tentativeness that often comes through the preaching of those who do not share a deep devotion to the Divine Persons. In this article, we will further explore St. Elizabeth’s devotion to the Trinity by reflecting on her understanding of adoration as an oblative reality characterized by peace and a distinctly Christian understanding of self-forgetfulness.

St. Elizabeth of the Trinity contemplates the Trinity as a mystery in which one can both “lose” and “forget” one’s own self. She does not explicitly refer to Christ’s observation that whoever loses his life for the sake of Christ will gain it forever (Mt 16:25). Yet she approaches the Divine Persons, asking for the grace to completely “lose” herself so that she might be established in peace, and sees the immensity of God as evoking self-forgetfulness and complete surrender to his love.

A severe spiritual trial during her novitiate helped forge this devotion. Her prioress and novice mistress, newly appointed thirty-one year old Mother Germaine, describes Saint Elizabeth struggling with “shadows of a dark night,” including “interior disturbances, spiritual pain, and strange phantoms.” Such an observation is entirely consistent with Carmelite tradition. In his commentary, Dark Night, St. John of the Cross argues that such testing is necessary to dispose the soul to perfect union with God, and even more, that this union is already being affected during the trials when he seems so absent. In Spiritual Canticle, St. John of the Cross makes even more explicit that this is a spiritual battle against the devil. Suffering the dark shadows of this spiritual trial in contemplative prayer, according to this wisdom, would prepare Saint Elizabeth for a profound and fruitful union with Christ, the Bridegroom.

From the Shepherds: St. John Vianney – A Saint of the New Evangelization, Part 2: The Priest as Catechist

From the Shepherds: St. John Vianney – A Saint of the New Evangelization, Part I

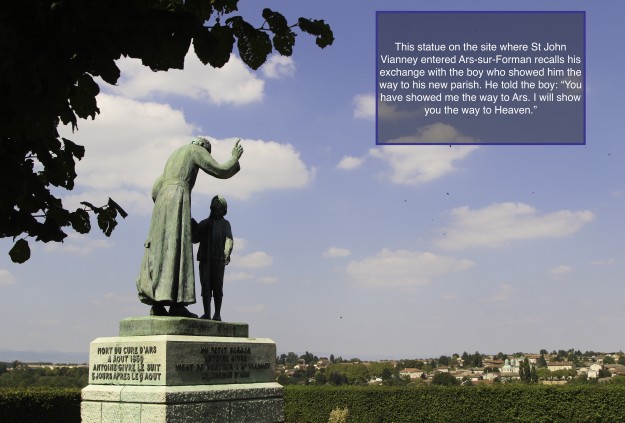

In this three-part series, I want to focus on a Saint of the New Evangelization who many of you will already have met in the Communion of Saints: St.

In this three-part series, I want to focus on a Saint of the New Evangelization who many of you will already have met in the Communion of Saints: St.