Youth & Young Adult Ministry – The Miracles God Can Work in Just Forty Hours a Week: The Fruits of Boundaries in Ministry

Who could survive a low-paying, time-consuming, unpredictable, and exhausting job for more than a few years? And if they do survive, who could possibly thrive, especially as a family? We are living proof that it is possible, but it takes an important skill that many of us were not taught: building and protecting boundaries.

The first requirement to continue in ministry for more than a few short years is, of course, knowing ourselves to actually be called by God to this work. When we are called by God, bringing others into a deeper union with Christ and his Church in a substantial and concrete way becomes our overarching purpose. All Christians have this call by reason of their baptism, but not everyone is called to make it his or her professional employment. When considering full-time ministry work, there are important questions about boundaries that require clear answers. Can we do God’s will to the fullest in just the forty hours a week we are hired for? Does having time clearly set apart when we are completely removed from work limit our ability to love and serve unconditionally? If we are not at every event or providing several weeknight activities each week, how will we reach people well?

From the Shepherds – A Half Century of Progress: The Church’s Ministry of Catechesis, Part Three

The General Catechetical Directory (1971) – Catechesi Tradendae (1979)

In this series of articles exploring a rather extraordinary fifty-year period in the Church’s catechetical mission, we have already considered the impact of the six International Catechetical Study Weeks. We now turn our attention to three pivotal catechetical documents promulgated at the level of the universal Church: the General Catechetical Directory(1971), and two apostolic exhortations, St. Paul VI’s Evangelii Nuntiandi (1974) and St. John Paul II’s Catechesi Tradendae (1979).

By the time the final report of the International Catechetical Study Week at Medellin, Columbia was published in 1969, the Holy See was well into the process of developing a catechetical directory for the universal Church. That process had been set in motion by the promulgation in 1965 of the Second Vatican Council’s Decree on the Pastoral Office of the Bishops in the Church Christus Dominus. It specifically prescribed that “directory should be composed concerning the catechetical instruction of the Christian people.”[1]

General Catechetical Directory (1971)

In June 1966, the task for implementing the conciliar mandate for a directory was given to the Congregation for the Clergy under the leadership of its prefect, Cardinal Jean Villot. At that time, the Congregation for the Clergy had the competence to oversee the Church’s catechetical ministry. (Pope Benedict XVI subsequently transferred that responsibility to the Pontifical Council for Promoting the New Evangelization.)[2] Cardinal Villot gathered an international commission in Rome in 1968 to plan the directory. The commission was also responsible for the composition of the directory and consulted with the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith and the Congregation for the Sacraments throughout the process. The commission also consulted directly with the world’s bishops. The commission developed a proposed outline, which was reviewed at a special plenary session of the Congregation for the Clergy. The Foreword to the Directory states, “After that, a longer draft was prepared, and once again the Conferences of Bishops were queried so that they might express their opinion about it. In accord with the advice and observations given by the bishops in this second consultation, a definitive draft of the Directory was prepared. Even so, before this was published, it was reviewed by a special theological commission and by the Sacred Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith.”[3] A draft text was developed and then released to all the episcopal conferences in the world for further consultation.

As is evident, the task of preparing a catechetical directory for the universal Church in a post-conciliar Church was not only challenging because of the nature of the task itself but also because of the methodology employed by the congregation; namely, an exhaustive process of multiple, multi-tiered, worldwide consultations. In fact, this rather cumbersome process became the standard for the preparation of the two succeeding catechetical directories of 1997 and 202,1 as well as for that of the Catechism of the Catholic Church.

The General Catechetical Directory was published on Easter Sunday, April 11, 1971, bearing the signature of Cardinal John Wright, who had by then become the prefect of the Congregation for the Clergy. Its purpose was “to provide assistance in the production of catechetical directories and catechisms.”[4]

A Return to the Kerygma: The Path to Renewal

If you find yourself in a fight, your extremities get cold. Your adrenaline kicks in and blood rushes to your core to pump your heart, support your lungs, and power your muscles so they can keep you alive. Moments of crisis are signals to get back to the heart of things. This isn’t only true of your body but of any institution. If a business is about to fail, it desperately needs to rush back to its “why”: Why do we exist? What are our core values? Are we being true to those values?

AD: St. John Bosco Conference for Evangelization & Catechesis, July 11-14

To learn more or to register for the St. John Bosco Conference, click here or call 740-283-6315.

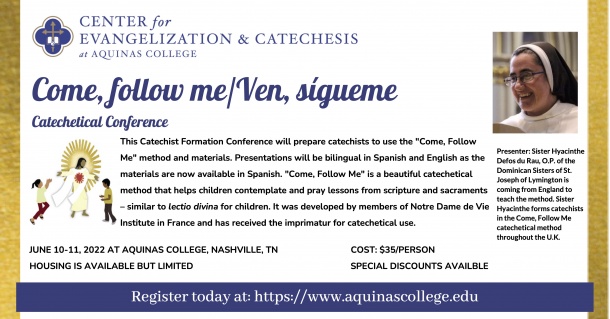

AD: Come, Follow Me Bi-lingual Training Conference, June 10-11, Nashville

Click here to register for this bi-lingual training in the Come, Follow Me method of catechesis.

AD: Order James Pauley's newly revised Liturgical Catechesis book!

To order James Pauley's Liturgical Catechesis in the 21st Century, Revised Edition, go to www.LTP.org or call 800-933-1800.

Falling in Love with the Church

Born into a Catholic family and baptized when I was sixteen days old, I grew up accepting the Church, receiving from her, but not understanding much about her identity.

Born into a Catholic family and baptized when I was sixteen days old, I grew up accepting the Church, receiving from her, but not understanding much about her identity.

More than a Birdbath: St. Francis of Assisi, a Living Instrument of Catechesis

Most people within the Catholic Church, as well as those who would consider themselves religiously unaffiliated, have some name and image recognition of St. Francis of Assisi. For many, the dominant image is the ubiquitous St. Francis birdbath nestled in the greenery or the flower garden. Others may think of Francis of Assisi’s particular love for the poor and the lepers of his day. For others, when they think of St. Francis, their consideration is drawn to the stigmata he received that resembled the wounds of the poor, crucified Christ.

These images all have a true connection to the man of Assisi, but there is one that often goes largely ignored: St. Francis of Assisi, the catechetical saint. The small yet substantive corpus of writings of Francis of Assisi reflect a powerful catechesis of the theology and spirituality of Catholic Christianity. Francis’ writings, mostly composed of prayers, letters, and Rules of Life for his followers, form a simple yet profound catechesis rooted in Scripture and expressive of the culture of Christendom in which Francis lived. In his writings, we are invited to meet a man who is described in an antiphon of the Liturgy of the Hours as a “thoroughly Catholic and apostolic man.” Francis was deeply rooted in the orthodox teaching of Catholic Christianity and committed to sharing this truth, which burned like a fire in his heart.

From the Shepherds – A Half Century of Progress: The Church’s Ministry of Catechesis, Part Two

We continue this series from the last issue of the Catechetical Review here in the "From the Shepherds" department because of its reflections on the writings of the bishops of the universal Church.

The five decades between the Second Vatican Council and the publication of the third general catechetical directory in 2020 have been an extraordinarily important period in the history of modern catechetics. During this time the Church’s catechetical ministry has been afforded unprecedented support in documents of the universal Church as well as those of the bishops of the United States. This series of articles is an exploration of those documents. Prior to the Council, however, six pivotal international catechetical study weeks were convened that previewed some of the major concerns raised in the deliberations of the Council fathers. In the first article of this series, the basic themes of the first three international catechetical study weeks held between 1959 and 1964 were explored. In this article, we will examine the issues engaged by the last three international catechetical study weeks held between 1964 and 1968.

Catholic Schools – Apostolicity: Guarding the Deposit of Faith

A frequently asked question from the young women I teach is, “Don’t you feel like it’s unfair that women can’t be priests?” As a woman working in the Church and teaching the faith, I think they expect me to feel cheated, as if my rights are being disrespected. While I have taken the time to consider the question and its implications, I would never change my answer: “Not at all!” The role I have is an absolute privilege and different roles do not mean unequal or unfair—they just mean different.

My job as a Catholic middle school religion teacher is a great privilege. Every day, I get to share the Gospel with my students. My classroom is a place where people are invited to know and love the Lord, where the Scriptures are spoken, where our story of salvation is told year after year. I have a fundamental task in the lives of my students. COVID or not, I am an “essential worker” in the vineyard of the Lord because what I teach must be shared. It affects the salvation of souls.