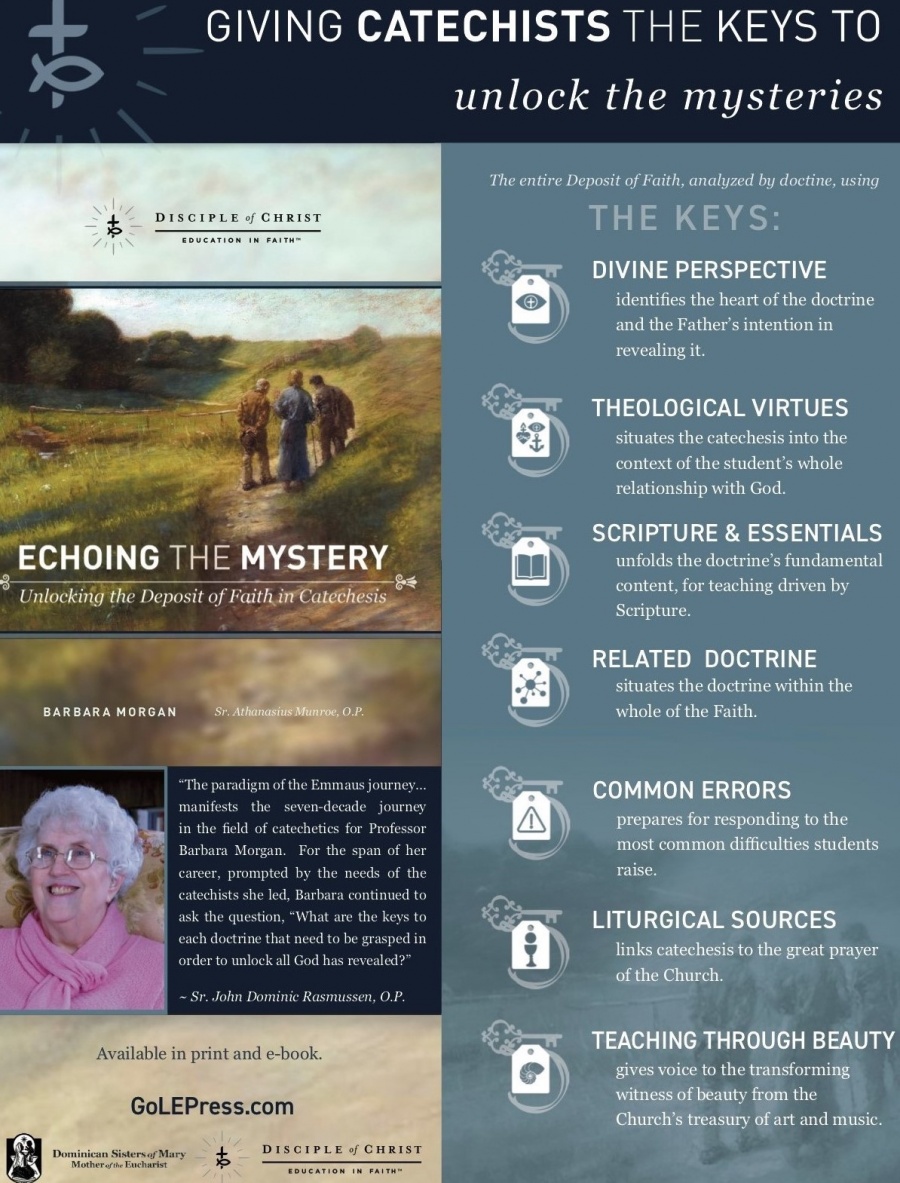

AD: Catechist resource to teach any age group in any setting

To learn more about Echoing the Mystery or to order click here.

This is a paid advertisement in the July-September 2021 issue. Advertisements should not be viewed as endorsements from the publisher.

Catholic Schools: Lessons Learned from an Iraqi School

"The Church is alive in Iraz, and Christ is alive in Iraq."

Pope Francis, March 7, 2021 Erbil, Iraz

On my fiftieth birthday, I received as a gift a detailed map of the world. The map holds pins of places traveled on behalf of Franciscan University of Steubenville and the names of cohort members in the Master of Catholic Leadership graduate program, of which I am the director. Each name on the map is significant as is the story of how they have come to their leadership role.

In March of 2021, I had the privilege of adding my own pin to this map. Along with Fr. David Pivonka, TOR, and Dr. Daniel Kempton, Vice President for Academic Affairs, I traveled to Erbil, Iraq at the invitation of Archbishop Bashar Warda. Our trip coincided with Pope Francis’s historic visit to Iraq.

Children's Catechesis: Forming Children &Teens as Missionary Disciples

In the 1997 General Directory for Catechesis, “Missionary Initiation” is listed as a sixth and unique task of catechesis. The 2020 Directory for Catechesis folds this task into the fifth task of catechesis, “Introduction to Community Life,” with the logic that an integral part of being formed in Christian community is learning to contribute to the growth of the community through our baptismal vocation as missionary disciples.[1] The Catechism of the Catholic Church calls mission work “a requirement of the Church’s catholicity,” meaning that because the Church is for all humanity, we must be a welcoming people, taking Christ’s message to others.[2] In fact, the Second Vatican Council called the Church “the universal sacrament of salvation.”[3] We are the visible sign to the world that Christ welcomes all to life in him. Taking Christ to the world is not only a collective responsibility, but also an individual one. In his encyclical letter Redemptoris Missio, Pope St. John Paul II calls missionary activity “a matter for all Christians.”[4] This includes, of course, the youngest Christians in our community, the children and teens we form in parish and school catechetical programs.

Notes

[1] See USCCB, Directory for Catechesis (Washington, DC: United States Conference of Catholic Bishops, 2020), no. 89.

[2] See Catechism of the Catholic Church, par. 849–856.

[3] Second Vatican Council, Lumen Gentium, no. 48.

[4] John Paul II, Redemptoris Missio, no. 2.

Youth & Young Adult Ministry: The Use of Media in Youth Ministry

It’s no secret that over the past year the use of media has become a near necessity, causing its importance in our youth programs to skyrocket. The conversation about what it looks like to effectively use media within the realm of youth ministry is more paramount today than it has ever been in the Church’s history.

There is certainly no lack of differing perspectives when it comes to the best media practices, and there’s not necessarily “one right way” to engage with the youth culture through media. But there are most definitely some dangers in regard to the use of media within youth ministry as well as some practices that can help us become lights in the lives of our young people.

Catholic Schools: Three Things I Love Most About Being a Catholic School Teacher

I’ve had the pleasure of being a certified teacher for twenty years now. I started my teaching career in a public school, and have spent the last five years teaching middle school students at a Catholic school outside of Phoenix, Arizona. Most teachers will agree that the greatest reward of teaching comes from watching students grow academically and socially. In a Catholic school we have an added bonus and responsibility, which is to help guide students as they form their spiritual life.

Our youth face the difficult task of navigating a social and public landscape that is often in opposition to the teachings of the Church. Being a catechist has become increasingly difficult with each passing year. Our children are bombarded with messages online, on television, and with their peers. Too often, these messages run counter to the Gospel. This is why it is more important than ever to teach the truth and to give young people the tools they will need to defend the faith. The best way to do this is to live the truth and teachings of the Church in our own lives.

The love we have for Our Lord should pour out of our hearts and be visible for all to see through not only our actions but our words. The old adage, “Don’t just talk the talk, walk the walk” comes to mind when I think about being an example for young people. Children need to see us at Mass and receiving the sacraments. Just recently, my students attended a retreat at which the Sacrament of Reconciliation was offered by several priests. There was a lull in the participation where children were looking to see who would go up next. I decided it would be a good idea to hop up and head into the confessional to demonstrate that I am a sinner in need of the Sacrament of Reconciliation just as much as they are. The kids looked a bit surprised, but I noticed when I got back to my pew to pray some of my reluctant students went up to receive Confession.

Here are the three things I love most about being a Catholic School Teacher:

Important Announcement for Today's Catholic Teacher Readers

Important Announcement Regarding the Future of Today’s Catholic Teacher Magazine

Dear Today’s Catholic Teacher Reader,

Creating a More Welcoming School: Addressing Culture and the Catholic Worldview

https://pixabay.com/photos/teacher-learning-school-teaching-4784916/The religious identity of students enrolled in Catholic schools is increasingly diverse. In most classrooms today, it is common to find students who identify themselves as Catholic, those who practice other religions, and some who are not religious. It goes without saying that a Catholic school would want all of its students, regardless of their religious orientation, to feel included in the school community. However, this goal must be achieved in a way that does not compromise the school’s ability to fulfill its distinct mission of educating, evangelizing, and catechizing its students. What, then, is the best approach for welcoming members of the school community who are not Catholic, while simultaneously catechizing those who are receptive to the faith?

Some schools, in an effort to welcome non-Catholic students, choose to “neutralize” the Catholic aspects of their school. They downplay the school’s Catholicity by reducing its visible signs on their website (e.g., removing overt references to its history). They also remove statues, crucifixes, and other religious art from public spaces and relocate them to private ones. Because requiring Catholic theology classes might appear to proselytize non-Catholic students, these schools adjust their curricula to be more flexible and open to individual differences. Participation in courses that address Catholic doctrine is made optional, or they adopt a “religious studies” approach that presents Catholicism within the broader context of world religions. In these schools the number of shared, faith-based events (e.g., Mass, Confession, and retreats) may be reduced or also made optional.

Admittedly, these efforts are likely to minimize the discomfort a non-Catholic might feel from certain aspects of a Catholic school experience. It makes sense that such actions would reduce the times when a student might confront concepts she does not understand, be invited to consider traditions that are different than her own, and be required to attend rituals in which she is unable to fully participate. Although the intentions behind these “neutralizing” actions might be considered good, their effect is not neutral and can be harmful.

Catechetical Methodology and its Application to the Lives of Human Beings

This article explores chapters 7-8 of the Directory for Catechesis.

Introduction and Context

It is now twenty-three years since I eagerly read the last General Directory for Catechesis and made efforts to implement its teachings within the catechetical programs in some of the Catholic schools in Australia. Much has changed in our world since 1997, and the new Directory for Catechesis has achieved an outstanding synthesis of what was sound and helpful in the earlier document, while taking us forward with new and profound insights for today. In this article, l will be addressing the essential contents of chapters seven and eight of the Directory, namely: “Methodology in Catechesis” and “Catechesis in the Lives of Persons.” Before doing so, however, I would like to frame my comments within the context of the Directory as a whole. Firstly, it is essential to understand that catechesis must now take place in a world overwhelmingly influenced by globalization and the digital culture. According to the Directory, there are advantages and disadvantages associated with both phenomena. The danger associated with globalization is the tendency towards international standardization, which puts pressure on local cultures. With regard to digital culture, there is an implicit tendency towards a “one size fits all” approach implicit in digital culture, which undermines an essential anthropological truth.[1] We must always keep in mind that every person is unique and unrepeatable.

It seems to me that there are three essential insights running through the document which could perhaps be summed up in three words: accompaniment, kerygma, and mystagogy. All of these themes appear multiple times in the document.

The emphasis on kerygma takes up a focus that began to appear strongly in Evangelii Gaudium, which had already taught that “all Christian formation consists of entering more deeply into the kerygma.”[2] It was also in this 2013 document that we were given a simple definition: “Jesus Christ loves you; he gave his life to save you; and now he is living at your side every day to enlighten, strengthen and free you.”[3] The Directory is insistent that in the initial stages of evangelization the primary focus should be on making present and announcing Jesus Christ. Moreover, at every step of the way, there can be no true evangelization if the name and teaching of Jesus Christ, the Son of God” are not proclaimed.[4]

Mystagogy, the Directory reminds us, is a liturgical catechesis highlighting the way in which the liturgy makes present the mysteries revealed in the Scriptures. It introduces us to the living experience of the Christian community, the true setting of the life of faith. It is a progressive and dynamic process, rich in signs and expressions and beneficial for the integration of every dimension of the person (DC 2). The emphasis on mystagogy has been regarded as foundational for catechesis since the publication of the Apostolic exhortation Sacramentum Caritatis in 2007.

Finally, those familiar with the work of Pope Francis will not be surprised with the highlighting of accompaniment. This notion occurs in the Directory more than any other. It acknowledges the pastoral difficulties being experienced at this time by so many in our world. We are asked to emphasize the mercy and love of God, who seeks out the lost and the lonely in our world.

Methodology in Catechesis

I have now spent more than thirty years thinking about issues of catechetical methodology, making this a significant component of my doctoral, post-doctoral, and practical work. I wish to affirm that in this chapter the Directory has drawn together all of the best practices of which I am currently aware in this field. The document soundly affirms that there can be no single method in catechesis—one size certainly does not fit all. What is more, it is made clear that catechesis is an event of grace, brought about by the word of God within the experience of the person. At the same time, it is grounded in an authentic Christian anthropology and guided by the demands of the Gospel (see DC 195). The example of the teaching of Jesus in the parables is offered as the best example of catechesis in action. In the parables, the same concrete and human image is offered to everyone, but the meaning is left to unfold in accordance with the work of the Holy Spirit in each person in their own time.

AD: New Book! An Evangelizing Catechesis, Teaching from Your Encounter with Christ

To order this book from Our Sunday Visitor click here. Or call (800) 348-2440.

This is a paid advertisement in the October-December 2020 issue.

Encountering God in Catechesis

Excerpts from two testimonies.

“Let the Children Come to Me” (Mt 19:14)

I have not been a catechist for a very long time; however, I was recently privileged to see how the Word of God calls to little children. The week’s lesson was entitled “The Greatest Gift of All” and the subject was the Holy Eucharist. My student is my seven-year-old son, who is as busy as all seven-year-olds are. Most of what I teach seems to go in one ear and out the other because on any given day, when asked what he learned that day, my son inevitably replies with a very charming smile, “I forget,” and immediately launches into an in-depth explanation of whatever he is building out of Legos. I was worried about presenting this lesson to my son because this was his first formal encounter with the Holy Eucharist in our catechetical lessons. I did not want to understate this truly greatest gift of all, but I was unsure if he would understand the Holy Eucharist—or even pay attention.

....

Witness to Christ

I have often wondered whether what I am teaching to my students is getting through. As a training instructor for the Secret Service it was easy enough to tell: successful practical exercises, making the correct decisions, shoot or don’t shoot, pass or fail. But, in teaching the faith, there is no surety. Even if the students pass a test, has it deepened their relationship with Christ? However, occasionally God has provided a glimpse at how, through me, he has changed lives.

I am in my second year as a religion teacher at John Paul the Great Catholic High School—still a “rookie” according to some of my associates. I have actually been in the classroom for over 10 years, though, training new recruits for the Secret Service. The difference: the recruits always wanted to be in my class.

Last year I learned a lesson that will stay with me for the rest of my high school teaching career....