Attaching to Mary: The Gesture of Pilgrimage

I come here often. Sometimes I come in gratitude. Other times I come here to beg. I come alone. I come with my wife and our kids.

Growing up, it took thirty minutes to get here. Back country roads. Flat. Everything level and straight. Fields speckled with the occasional woods, a barn, a farmhouse. It was practically in my backyard. But then I moved. Now, it takes about three hours. I drive up the long interstate to those familiar country roads that lead into the village.

The sleepy, two-stoplight town is something of a time warp. Life just moves slower in Carey, Ohio. The rural way of life is simpler than the suburban variety.

I stay for hours, or for twenty minutes. Being here is all that matters.

Yes, I come here often. It’s in my blood.

I am a pilgrim.

Basilica and National Shrine of Our Lady of Consolation

In June of 1873, Fr. Joseph Peter Gloden was entrusted with the mission in Carey, Ohio: thirteen families and an unfinished church building. The people were discouraged. But Fr. Gloden rallied the small band of Catholics, and the nascent congregation finished the construction of the church. It was given the title Our Lady of Consolation, for, as Gloden said, “We are not yet at the end of our difficulties and we need a good, loving and powerful comforter.”[1]

After the church was dedicated, Gloden, originally from Remerschen, Luxembourg, sought to obtain a copy of the statue of Luxembourg’s Our Lady of Consolation. The statue was made of oak and adorned with a fabric dress. The replica of the statue from the Cathedral of Luxembourg arrived in Carey in March 1875. To give Our Lady’s statue a most solemn entrance into her new home, Fr. Gloden and his parishioners decided on a seven-mile procession to the church in Carey from the nearby parish in Frenchtown, Ohio.

The big event was to take place on May 24, 1875. The day before, a heavy storm swept through the area. On the morning of the proposed procession, another storm threatened. Lightning could be seen across the horizon. Gloden urged the crowd not to scatter, calling out, “Let the procession proceed; there is no danger.”[2] And so they charged into a thunderstorm. The rest is history. Rain poured all around the procession, but nobody in the procession got wet. Once the statue reached the church and was safely inside, the rain pelted the earth.[3] From the beginning, the whole thing was viewed as a miraculous event—a light prelude to events that would happen in Fatima some decades later. On that day in rural Ohio, Mary protected her beloved little ones from the elements.

Lessons Lourdes Offers to Evangelists and Catechists

Many were the attempts made in Europe during the nineteenth century to redefine and refashion human existence. Significantly, over the same period there were three major apparitions in which Mary, Mother of the Redeemer, was present: Rue du Bac in Paris, France (1830); Lourdes, France (1858); and Knock, Ireland (1879). Taken together, these offer the answer to humanity’s searching. Let us look particularly at Mary’s eighteen apparitions to Bernadette Soubirous in Lourdes.

In February 1934, one year after Bernadette’s canonization, Msgr. Ronald Knox preached a sermon in which he compares the young girl’s experience with that of Moses, even suggesting we might see Lourdes as a modern-day Sinai.[1] We should note that the events on Sinai are at the heart of biblical revelation, whereas those in Lourdes were private revelations later acknowledged by the Church to be for our good; yet, Knox finds many similarities between the two. Both, for example, took place on the slopes of hills; Moses and Bernadette were shepherds at the time; for both, a solitary experience resulted in the gathering of great crowds. Moses took off his shoes out of reverence for holy ground; Bernadette removed hers to cross a mill stream. Each was made aware of a mysterious presence demanding their attention: for one, by a fire that burned but did not consume; for the other, at the sound of a strong wind that did not move trees and the sight of a bright light that did not dazzle.

Moses was to lead the people out of bondage, though the Hebrews fell back to the worship of a golden calf. Knox writes that Bernadette was also “sent to a world in bondage,” a bondage in which it rejoiced. He finds significance in the fact that her visions took place in the middle of the Victorian age, when material plenty had given rise to materialism, “a spirit which loves . . . and is content with the good things of this life, [which] does not know how to enlarge its horizons and think about eternity.” Bernadette “was sent to deliver us from that captivity of thought; to make us forget the idols of our prosperity, and learn afresh the meaning of suffering and the thirst for God.” “That,” Knox uncompromisingly affirms, “is what Lourdes is for; that is what Lourdes is about—the miracles are only a by-product.” The preacher has no doubt of our own need for this message: “We know that in this wilderness of drifting uncertainties, our modern world, we still cling to the old standard of values, still celebrate . . . the worship of the Golden Calf.”

The Witness of Mary: A Portrait of Doctrine

In Evangelii Nuntiandi (EN), Pope Paul VI, of sainted memory, said something that has become almost a banner that we fly above our apostolic work today, both in our evangelization and our catechesis. “Modern man listens more willingly to witnesses than to teachers, and if he does listen to teachers, it is because they are witnesses.”[1] This is often taken to mean that teaching, both the act and its content, are somehow to be considered a second-rate concern for our mission today.

The almost ubiquitous line is, “Well, doctrine is important, but . . ..” In statements of this kind, the implication is that what follows the ellipsis—whether it be encounter, the heart, the personal dimension, or, as in Pope Paul’s statement, Christian witness—is primary, and that doctrine is secondary. Unfortunately, in some cases these statements are really intended to communicate that content isn’t very important at all.

Marian Devotion and the Renewal of Church Life

What happened to Mary? This is a question that could easily occur to anyone reading through 20th-century theology. Marian theology up to the 1960s was vibrant and flourishing. Fr. Edward O’Connor’s 1958 magisterial volume The Immaculate Conception (recently re-released by University of Notre Dame Press) seems to sum up an era. The lively essays harvest the best of traditional theology and seem poised to surge ahead, bursting as they are with both creativity and fidelity. And yet, ten years after its publication, Marian study was nearly dead. This book remains unsurpassed in its field.

What happened to Mary? This same question could be asked by anyone old enough to remember Marian piety before 1968, even if, as is more and more likely now, they were only children at the time of Vatican II, which closed that year. Marian piety had seemed so alive and well that it seemed unthinkable that it could be dislodged. But within ten years of the Council, it had all but vanished.

What happened to Mary? This same question is most likely not to be asked by Church members who grew up in the post-conciliar Church. The tragedy of any enduring loss is that eventually no one notices anything is missing. When one’s spiritual sensibilities have been dulled through lack of use, one lives an impoverished spiritual life without even realizing it. The question is not likely to occur to those born in the 70s or later, unless, perhaps, they travel to regions in the world or encounter subcultures within our own society where Marian devotion is alive and well. The encounter can almost seem shocking to the person whose spiritual sensibilities are thereby newly awakened. They might very well be prompted to ask, “But what happened to our Mary?”

Editor's Reflections — Mary: The First Disciple of Jesus

What does it mean to be a disciple?

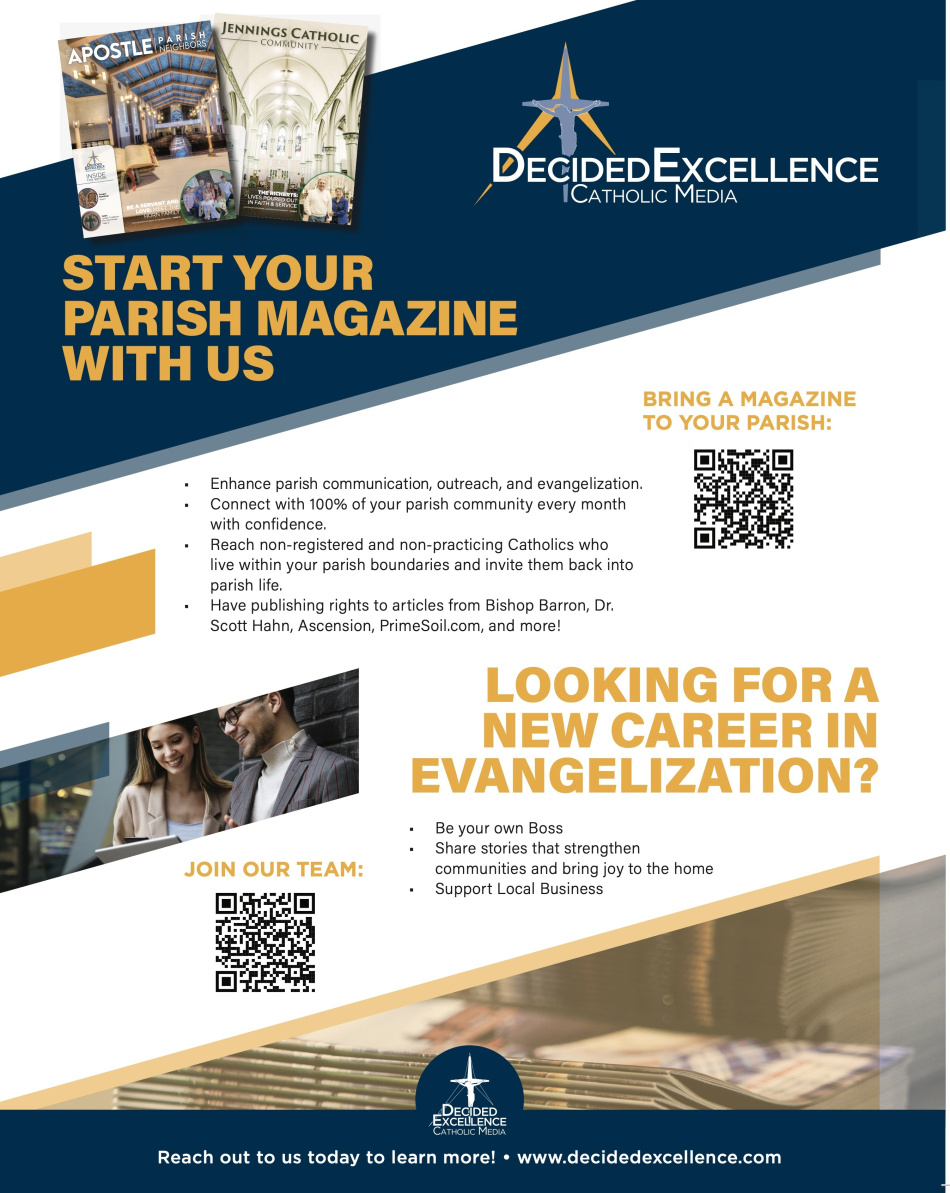

AD: Decided Excellence Catholic Media

This is a paid advertisement in the January-March 2024 issue. Advertisements should not be viewed as endorsements from the publisher. To find out more, go to www.decidedexcellence.com or email at [email protected].

Witnessing to Life

As Christians, we are called to affirm the dignity of each human being. This dignity has its beginning from our first moment of existence, when each of us receives the gift of life itself. The Catechism of the Catholic Church teaches that “Human life must be respected and protected absolutely from the moment of conception. From the first moment of his existence, a human being must be recognized as having the rights of a person—among which is the inviolable right of every innocent being to life” (2270).

Made in God’s image, each human being possesses an intellect and will, along with the capacity to love and be loved.[1] When we live in accordance with our dignity, what we were truly made for, it causes deep happiness and fulfillment. When we witness to a culture of life, we help uphold the dignity of everyone around us.

Notes

[1] See CCC, nos. 1704–5.

RCIA & Adult Faith Formation: Forming Missionary Disciples as Prophets and Witnesses

In 2017, the bishops of the United States held a convocation focused on unpacking and applying Pope Francis’ Apostolic Exhortation Evangelii Gaudium (“The Joy of the Gospel”). It was a beautiful moment of solidarity around the essential mission of the Church. Throughout the convocation, the bishops often repeated the mantra “We all are missionary disciples!” That phrase certainly echoes Pope Francis’ words in Evangelii Gaudium, “In virtue of their baptism, all the members of the People of God have become missionary disciples,” but it also reflects a desire in the American episcopate for the faithful to embrace the mission of evangelization and live out their identity as missionary disciples of Jesus Christ.[1]

This expressed desire has inspired many efforts to form evangelizers and missionary disciples at the diocesan, parochial, movement, and apostolate levels. These formation opportunities have helped the Church ask more specific questions, such as: What does a missionary disciple need to know? What skills are necessary for missionary discipleship? Given the wide array of pastoral gifts, abilities, and methods, are some more pertinent or necessary than others? How long does it take to form a missionary disciple? These questions are all relevant, even important. But in forming a missionary disciple, there is one key question: how does baptism make one a missionary disciple? Understanding the answer to this question helps catechists and leaders to approach formation from a position of collaboration with what God is already doing rather than what we hope he wants to do.

Notes

[1] Pope Francis, Evangelii Gaudium, no. 120.

Applied Theology of the Body: Gender Ideology and Homosexuality

Pope St. John Paul II proclaimed the theology of the body (TOB) as perennial truths revealed by God through ancient biblical texts, but he also noted that this pedagogy of the body “takes on particular importance for contemporary man, whose science in the fields of bio-physiology and bio-medicine is very advanced” (TOB 59:3).[i] While he acknowledged the value of modern science for certain kinds of truth, he cautioned that such science does not develop “the consciousness of the body as a sign of the person” because “it is based on the disjunction between what is bodily and what is spiritual in man,” which leaves the body “deprived of the meaning and dignity that stem from the fact that this body is proper to the person” (TOB 59:3). In “a civilization that remains under the pressure of a materialistic and utilitarian way of thinking and evaluating” (TOB 23:5), this depersonalized notion of the body encourages people to treat the body as an object to be manipulated and used for their own subjective gratification.

In 2019, the Congregation for Catholic Education (CCE) promulgated Male and Female He Created Them, which identifies this same disjunction between the body and the spirit as the fundamental tenet of the gender theory linked with the so-called sexual revolution.[ii] Over the course of the twentieth century, this gender theory became an “ideology of gender” that absolutizes and weaponizes pseudoscientific concepts to establish a sharp dichotomy between the conscious individual (gender) and the body (sex) and to dictate social outcomes that serve the agenda of the sexual revolution (CCE, no. 6). On the surface, it looks like a very modern example of bad philosophy and dubious science. But from the perspective of TOB, gender ideology is an attempt to establish a cultural framework that glorifies the most degrading components of the concupiscence and lust that have plagued humanity since the advent of sin.

The gender ideology of the sexual revolution corresponds directly to the concerns about contemporary culture that led St. John Paul II to proclaim TOB, and it remains one of the most important reference points for the application of TOB in the modern world. This installment of the series summarizes the main components of this gender ideology that deviate from the meaning of human sexuality found in TOB. Additionally, this installment examines the issue of homosexuality as a prominent example of how this gender ideology clashes with TOB at the level of sexual morality.

Notes

[i] John Paul II, Man and Woman He Created Them: A Theology of the Body, trans. Michael Waldstein (Boston: Pauline Books and Media, 2006), cited parenthetically in text as TOB.

[ii] Congregation for Catholic Education, Male and Female He Created Them: Towards a Path of Dialogue on the Question of Gender Theory in Education (Vatican City, 2019), nos. 8, 20. Cited parenthetically in text as CCE

Radically Available

In prayer after receiving Holy Communion, I recognized in my heart the voice of God the Father. “I want you to be radically available.” As Director of Religious Education in a large parish, I had an idea of what it meant to be radically available while working full time. It meant being available to God by showing up for daily Mass and prayer. It meant being available to my family for quick phone calls or spontaneous lunch meetings and for celebrations and vacations. It meant planning ahead but holding my plans loosely so I was interruptible. It meant keeping my office door open, welcoming parents or catechists who needed to talk.

Available to Rest in God’s Love

But why, I wondered, did God speak this phrase to me as I was retiring? I concluded that I was not to make any ongoing volunteer commitments but to trust God to lead me each day. For a couple of weeks, I delighted in unhurried phone conversations, invitations to travel, writing letters, cleaning neglected closets and corners, and catching up with friends over coffee after morning Mass.

Yet, I wondered, had I rightly understood the call to radical availability? Wasn’t it selfish of me to say no when my calendar was empty and I was qualified to help? What if I was taking the idea of radical availability too far? When I took my doubts to my husband and my spiritual director, they affirmed my discernment and encouraged me to stay the course.