Many moons ago, when I was a young social work student in North Dakota, I was required to take a course called “Indian Studies.” One of the books for the course was titled Black Elk Speaks. It was the moving account of the experience of the life of indigenous peoples prior to the arrival of the white European settlers, as seen through the eyes of a Lakota elder named Nicholas Black Elk. John Neihardt, the man who penned the book in the early 1930s, had a sense of the urgent need to preserve a record of what native life was like prior to the arrival of the white settlers, before the memory of “the old ways” was lost.

Many moons ago, when I was a young social work student in North Dakota, I was required to take a course called “Indian Studies.” One of the books for the course was titled Black Elk Speaks. It was the moving account of the experience of the life of indigenous peoples prior to the arrival of the white European settlers, as seen through the eyes of a Lakota elder named Nicholas Black Elk. John Neihardt, the man who penned the book in the early 1930s, had a sense of the urgent need to preserve a record of what native life was like prior to the arrival of the white settlers, before the memory of “the old ways” was lost.

Neihardt conducted an extensive interview with Black Elk, who was known to have been present as a teenager at the Battle of the Little Bighorn (also known as Custer’s last stand) in 1876. The interview was conducted with the assistance of his son, Ben Black Elk, as an interpreter.

Neihardt’s desire was to capture a snapshot of the “pre-contact” experience of native people. It is understandable that he didn’t bother with the rest of the story—that was not his interest. The book offers a caveat in its subtitle: “as told through John Neihardt.” The preposition is important because Neihardt took many artistic and poetic liberties in retelling Black Elk’s story. Neihardt regales his readers of the details of Black Elk’s early boyhood, his intense spiritual visions, the arrival of the “wasi'chu” (white people), the death of Custer, his adventures in Europe with Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Show, his involvement in the Ghost Dance religion, and other episodes of his life. The story ends just after the tragedy at Wounded Knee in 1890 with the image of Black Elk as an old man, standing on the highest peak in the Black Hills, weeping for a beautiful dream that had died.[1]

As moving as that image is, it is hardly the true end of the story. For one thing, the book ends when, in Black Elk’s own lifetime, the tragedy at Wounded Knee (1890) had just happened. It was, in fact, the point at which the Lakota people despaired of ever being able to resume their previous way of life. This was a natural place for Neihardt to set the story down, having achieved the project’s aim. However, Black Elk himself was not the despairing old man depicted by Neihardt—he would have been a scant 27 years old at that time. Fourteen years later he was baptized into the Catholic faith. Neihardt was not interested in that part of Black Elk’s story, but that is where the story of the catechist and now Servant of God Nicholas Black Elk really begins.

Before he was baptized, Black Elk was a traditional Lakota medicine man. One of his friends who had accepted the faith had encouraged him to give up the practice and become Catholic, but Black Elk was not immediately persuaded. However, his daughter Lucy recounted the event that changed the trajectory of his life. When he was called in his role as a medicine man to the bedside of a dying child, he met a Jesuit priest who had been called to administer last rites to the same child. Suffice it to say, their initial encounter would not have met today’s standards for cultural sensitivity. After a rather rude confrontation, Black Elk exited the scene and stood outside. When the priest completed the rites, he stepped outside to find Black Elk looking “downhearted and lonely—as though he had lost all his powers.”[2]

Black Elk perceived the holiness and the authority of the priest, and he sensed that the powers that the priest was calling upon were of a higher order. He reasoned that such power should not be resisted. The priest invited Black Elk to accompany him in his buggy, and they went back to the Holy Rosary Mission together. Black Elk spent the next two weeks there taking instruction in the Catholic faith. He was baptized on the feast of St. Nicholas and took the saint’s name as his Christian name. According to his daughter, he never practiced as a medicine man again.[3]

Nicholas received continued formation in the Saint Joseph’s Society, a men’s sodality that met for ongoing catechesis. To extend their mission among the Lakota people, the Jesuits often enlisted the talents and labor of lay catechists to provide instruction in the native language. Shortly after his baptism, Nicholas became a catechist, traveling a radius of hundreds of miles from the mission in Pine Ridge on foot, on horseback, or in a horse-drawn cart.

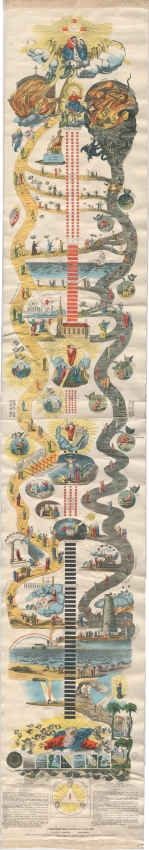

One of the principal tools he used was called the Two Roads Catechism, also known as a Ladder Catechism. Composed by Fr. Albert LaCombe, OMI, the catechism was a scroll of pictures that depicted the key moments in salvation history and Church history. It takes its name from the two roads that border the unfolding of the story—one road that leads to heaven, the other to hell. The theological virtues of faith, hope, and charity line up alongside the good road, and the deadly sins alongside the bad road.

Starting with the Holy Trinity at the bottom of the scroll, it depicts God creating the world, then the creation of Adam and Eve. It illustrates their fall from grace, the Great Flood, the Tower of Babel, the story of Moses, the Exodus, the Ten Commandments, the Ark of the Covenant, the Kingdom of David and the construction of the Temple, the ministry of the prophets, John the Baptist, the birth of Christ, the Passion, Death, and Resurrection of Christ, and the establishment of the Church. It also depicts a path diverting from the good road to the bad road, titled “the heresies.” The catechism also shows the age of discovery, a great ship setting sail on the ocean, which enabled Black Elk and other missionaries to contextualize the arrival the good news for those they were catechizing.

The Ladder Catechism weighed only a few ounces, making it extremely portable. Nicholas could lay the scroll on the ground and tell “The Story,” enabling both adults and children to visualize and understand the continuity of the Lord’s unfolding plan—in their native language. There is little doubt that the native Catholic children had a better grasp of the scriptural foundations of our faith than did their counterparts among the white settlers.

It is worth considering what possibilities a tool like the Two Roads Catechism might offer to contemporary catechesis. We know that children appreciate pictures, but even adults can benefit from seeing the continuous nature of the story from the beginning of time.

In 2012, a delegation of Lakota Catholics attended the canonization of St. Kateri Tekakwitha in Rome. One member of that delegation was George Looks Twice. At one point during the canonization Mass, George leaned over to the man sitting next to him and said, “I wish they would do something like this for my grandpa.” The man said, “Oh? Who is your grandpa?” “Nick Black Elk,” George replied.[4]

George didn’t know it, but he was speaking with Mark Theil, the archivist at the Marquette University Library that houses all the records of the Jesuit missionaries. When he got home, Theil did some research, revealing that Nicholas Black Elk could be credited with more than four hundred baptisms among the native people of the Great Plains. Further research revealed that there was, indeed, enough evidence of a life of holiness to open a cause for canonization. He encouraged the Diocese of Rapid City to look into it. After a petition was circulated, the cause was opened by Bp. Robert Gruss in October of 2017.[5]

We can learn much from the character and the ministry of the Lakota catechist Nicholas Black Elk, but three things in particular stand out: zeal, simplicity, and humility. Zeal for the Lord’s house consumed him,[6] driving him to undertake long and arduous journeys throughout the Dakotas and surrounding regions to bring the Good News of Jesus Christ to his people. He was, by all accounts, a missionary disciple. His Lakota language did not provide for theologically sophisticated arguments, but the Two Roads Catechism enabled him to explain things simply and accurately in his own language. Finally, Nicholas Black Elk had the emotional intelligence to understand the difficulty that many of his fellow Lakota had with letting go of the “the old ways.” He was gentle and accepting, respectful of each one’s freedom and individual journey of processing so much that was new and confusing. In our contemporary world, with the collision of cultures we are currently experiencing, we need his example, prayers, and inspiration more than ever.

Dr. Carole Brown is Executive Director of the Sioux Spiritual Center, a Catholic retreat house in the Diocese of Rapid City. www.siouxspiritualcenter.org

Notes

[1] John G. Neihardt, Black Elk Speaks (1932; repr. Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press, 1998).

[2] Michael F. Steltenkamp, Black Elk: Medicine Man, Missionary, Mystic (Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press, 2009), 90–91.

[3] Ibid.

[4] Damian Costello and Jon Sweeny, “Black Elk, the Lakota Medicine Man Turned Catholic Teacher, Is Promoted for Sainthood,” America Magazine (October 16, 2017), https://www.americamagazine.org/faith/2017/10/01/black-elk-lakota-medici....

[5] See Laurie Hallstrom, “Black Elk, The Cause for Canonization is Open,” Black Elk Canonization, November 2017, https://blackelkcanonization.com/cause-open/.

[6] C.f. Ps 69:10; Jn 2:17.

This article originally appeared on pages 32-33 in the printed edition.

Art Credit: The Ladder Catechism is from the Bureau of Catholic Indian Missions collection, courtesy of Marquette University

This article is from The Catechetical Review (Online Edition ISSN 2379-6324) and may be copied for catechetical purposes only. It may not be reprinted in another published work without the permission of The Catechetical Review by contacting [email protected]