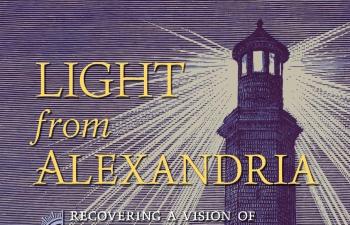

For an average Catholic, even one who speaks piously of the Mass as the re-presentation of the sacrifice of Calvary, the link between Christ’s dramatic death on the Cross can seem remote from the sacred liturgy’s formal ritual. The notion of the Mass as a sacred meal comes from its roots in the Last Supper, and the Eucharistic Prayer conspicuously repeats the very words of Christ at the Passover meal of the Upper Room. But historically, the Mass is also called a sacrifice. Even the Second Vatican Council’s constitution on the liturgy, Sacrosanctum Concilium, calls the Mass a sacrifice nine times and urges the laity to join themselves to the sacrifice offered by the priest. Yet, sacrifice of the ancient type is utterly unfamiliar to the modern world. Though its mechanisms are on vivid display in the Mass and its priestly and sacrificial logic is present, the sacrificial aspects of the Eucharist can seem only opaquely present rather than radiantly and fruitfully perceived. A little-known book by an author of great intellect provides a helpful interpretive guide in seeing how the Mass makes present the sacrifice of Christ: Jean Hani’s The Divine Liturgy: Insights into Its Mystery.[1]

For an average Catholic, even one who speaks piously of the Mass as the re-presentation of the sacrifice of Calvary, the link between Christ’s dramatic death on the Cross can seem remote from the sacred liturgy’s formal ritual. The notion of the Mass as a sacred meal comes from its roots in the Last Supper, and the Eucharistic Prayer conspicuously repeats the very words of Christ at the Passover meal of the Upper Room. But historically, the Mass is also called a sacrifice. Even the Second Vatican Council’s constitution on the liturgy, Sacrosanctum Concilium, calls the Mass a sacrifice nine times and urges the laity to join themselves to the sacrifice offered by the priest. Yet, sacrifice of the ancient type is utterly unfamiliar to the modern world. Though its mechanisms are on vivid display in the Mass and its priestly and sacrificial logic is present, the sacrificial aspects of the Eucharist can seem only opaquely present rather than radiantly and fruitfully perceived. A little-known book by an author of great intellect provides a helpful interpretive guide in seeing how the Mass makes present the sacrifice of Christ: Jean Hani’s The Divine Liturgy: Insights into Its Mystery.[1]

A professor at the University of Amiens in France, Hani’s academic specialty was comparative religions, studying ancient cultures steeped in sacrifice, including Judaism. A Catholic himself, Hani was interested in revivifying Catholic worship by reengaging it with its sacrificial origins in order to counter what he called the “sterilization of the imaginative side” of Christianity (4). For teachers and preachers today, his insights can help lead believers into a deeper understanding of the words of the Council that tie together both meal and sacrifice in the Mass: “At the Last Supper . . . our Savior instituted the eucharistic sacrifice of His Body and Blood . . . to perpetuate the sacrifice of the Cross throughout the centuries until He should come again, and so to entrust to His beloved spouse, the Church, a memorial of His death and resurrection.”[2]

The Nature of Sacrifice

The English word sacrifice comes from two Latin roots, sacra, meaning “holy” or “sacred,” and facere, meaning “to make” or “to do.” So, the goal of any sacrifice is to do the sacred action with the intent of making things holy. Hani rightly establishes why the Mass is indeed a sacrifice: it re-presents and makes real the sacrifice of Christ in order to make creation holy again after the Fall. By immolating a victim, literally “grinding” it up (from Latin molere, “to grind”), two ends were hoped for: reconciliation, which means being friendly again after a division, and propitiation, gaining or regaining the favor of another (7). In Christ’s case, his perfect self-offering did both: it healed the relationship between God and man perfectly, then made it possible to receive God’s sanctifying grace. In Eden, logically, humans had no need to offer sacrifice since the relationship between God and man had not yet been wounded by the Fall. And so Hani notes, “man quite naturally made that gift to God which is the obligatory response of the creature to the Creator, an absolutely pure gift, entirely spiritual: the gift of the heart” (14). After the Fall, however, humans no longer had the capacity for perfect spiritual giving. So, in his mercy, God “imparted to man the sacrifice [he] desired and determined . . . as a way of remedying this spiritual catastrophe” (14). In other words, God himself taught man how and why to offer sacrifice.

To show how the Mass fulfills the Old Testament requirements, Hani explains the complex array of Jewish sacrifices (8–11). Some were bloodless, such as the minha, with its flat breads made of flour and oil, some of which were burned completely and some eaten by priests on the Sabbath. Others were blood sacrifices, such as the holocaust, or olah, in which a bull was bled to death and then totally consumed by fire. The Sacrifice of Peace, or zebah shelamin, was a communion sacrifice in which the blood and fat of an animal was burned completely, while the rest was served for both priests and the faithful at a banquet. Notably, at the moment of communion with the flesh of the animal, Psalm 116 was read: “What shall I render unto the Lord for his goodness to me? I will take the cup of salvation and call upon the Name of the Lord,” a psalm later introduced to the Mass, recited by the priest after receiving the host. The most important Jewish feast was Passover, also a communion sacrifice, which involved the sacrifice of a paschal lamb both at the Temple and in individual homes, followed by a meal in which the victim was eaten in remembrance of the passage of the Israelites to the Promised Land. In other words, it became sign of passage from death to new life, answering the need established in Eden generations earlier.

In each case, the sacrifices involved immolation, death, and new life. Most evident is the holocaust, in which blood, which represents life, was drained from the animal’s body, then its flesh consumed by fire. The resulting smoke was said to take the sacrifice to heaven and therefore to God. Even the seemingly innocuous bloodless sacrifice of flat breads involved immolation through the grinding up of grains of wheat. Moreover, the twelve breads represented the twelve tribes of Israel (8), and so burning some and consuming others gave it overtones of holocaust and communion. In each case, the things sacrificed stood in for people, and after it was offered, it was eaten in a ritual meal. So when Christ equated the sacrifice of his own body with the breaking of bread—and thereby linking sacrifice with a meal—it would have been both strangely familiar and yet shockingly new. Christ was now priest and victim.

The rest of this online article is available for current Guild members.

This article is from The Catechetical Review (Online Edition ISSN 2379-6324) and may be copied for catechetical purposes only. It may not be reprinted in another published work without the permission of The Catechetical Review by contacting [email protected]