The United States Conference of Catholic Bishops is currently undertaking a Eucharistic revival. The idea for it began in 2019 when the bishops decided that we needed to respond to the moment of crisis in belief in the Eucharist in which we find ourselves—not only the discouraging results of the 2019 Pew study that reported that less than 30 percent of Catholics believe in the real presence of Jesus in the Eucharist but also the yet-unknown impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the Eucharistic practice of Catholics.[1] The response to the idea from the body of bishops has been enthusiastic, and many see it as an important moment in the life of the Church in the United States. Certainly, if we can hold up Christ in the Eucharist, he will draw more people to himself.

The United States Conference of Catholic Bishops is currently undertaking a Eucharistic revival. The idea for it began in 2019 when the bishops decided that we needed to respond to the moment of crisis in belief in the Eucharist in which we find ourselves—not only the discouraging results of the 2019 Pew study that reported that less than 30 percent of Catholics believe in the real presence of Jesus in the Eucharist but also the yet-unknown impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the Eucharistic practice of Catholics.[1] The response to the idea from the body of bishops has been enthusiastic, and many see it as an important moment in the life of the Church in the United States. Certainly, if we can hold up Christ in the Eucharist, he will draw more people to himself.

I will not focus here on the specifics of the revival, but I do want to talk about one of the deeper issues of the revival that connects with the work of catechesis. The Eucharist, which is the source and summit of our whole lives as Christians, is essential to catechesis. In fact, the Eucharist wants to catechize us about the essence of the Christian life.

We are all familiar with the famous words of the Second Vatican Council:

The other sacraments, as well as with every ministry of the Church and every work of the apostolate, are tied together with the Eucharist and are directed toward it. The Most Blessed Eucharist contains the entire spiritual boon of the Church, that is, Christ himself, our Pasch and Living Bread, by the action of the Holy Spirit through his very flesh vital and vitalizing, giving life to men who are thus invited and encouraged to offer themselves, their labors and all created things, together with him. In this light, the Eucharist shows itself as the source and the apex of the whole work of preaching the Gospel.[2]

In other words, everything we do in preaching the Gospel has one goal: to bring people to the Eucharist. Why? Because this is where we encounter Christ himself, where he gives us his life, and where he teaches us how to fulfill the meaning of our lives. He is the source and the summit.[3] The Eucharist is not only a place to encounter Jesus and receive his life, the source, but also the place where we give him ourselves in worship, the summit. It is where we offer ourselves, our labors, and all created things, together with Christ, which fulfills the reason we were created.

The Eucharist as Sacrifice

To my mind, this sacrificial aspect of the Eucharist is very much neglected in our catechesis, perhaps even more neglected than the Church’s teaching on the real presence. Yet this is the fullness of what it means to live a Eucharistic life! The Eucharist wants to teach us to make our own lives a gift. We need to catechize people about this aspect of the Eucharist in order that they might fully live their Christian lives.

This aspect of the Eucharist reveals to us the whole purpose of our lives, why we were created in God’s image. St. John Paul II loved to quote the Second Vatican Council, which taught: “man, who is the only creature on earth which God willed for itself, cannot fully find himself except through a sincere gift of himself.”[4] None of us will be happy unless we learn to make a gift of ourselves. Isn’t this what Jesus taught when he said, “This is my Body given up for you”? St. John Paul II’s whole theology of the body is rooted here. So is St. Paul’s theology of living in Christ: “he died for all, that those who live might live no longer for themselves but for him who for their sake died and was raised” (2 Cor. 5:15); “I have been crucified with Christ, it is no longer I who live but Christ who lives in me” (Gal 2:19–20).

The Eucharist is more than just an encounter with love. It is that; it is the most profound encounter with love possible in this life. But the Eucharist is more than just receiving a gift. We are meant to be transformed by this gift. Pope Benedict XVI writes in his encyclical on love, “The Eucharist draws us into Jesus' act of self-oblation. More than just statically receiving the incarnate Logos, we enter into the very dynamic of his self-giving.”[5] The Eucharist wants to change us into lovers in a twofold movement: Jesus comes to us to encounter us in his love, then this love transforms us.

At the heart of the Eucharist are the words of Jesus: “This is my body given up for you”; “This is my blood poured out for you.” These words cannot be understood independent of Jesus’ death on the Cross. They are intimately united with his death—they reveal its meaning. Similarly, these words without his death would be empty. The Crucifixion would be a mere execution. However, because of his death they express a real gift of himself. Through the words of consecration his death lives on and gives life to all time.

We know this truth from our sacramental theology:

When his Hour comes, he lives out the unique event of history which does not pass away: Jesus dies, is buried, rises from the dead, and is seated at the right hand of the Father “once for all” [Rom 6:10; Heb 7:27; Heb 9:12; cf. Jn 13:1; Jn 17:1]. His Paschal mystery is a real event that occurred in our history, but it is unique: all other historical events happen once, and then they pass away, swallowed up in the past. The Paschal mystery of Christ, by contrast, cannot remain only in the past, because by his death he destroyed death, and all that Christ is—all that he did and suffered for all men—participates in the divine eternity, and so transcends all times while being made present in them all. The event of the Cross and Resurrection abides and draws everything toward life. (CCC 185)

How does this event abide in our midst? It is through the Mass, the celebration of the Eucharist. Here we see the twofold nature of Christ’s death on the Cross. Christ’s Crucifixion is a gift of his life for us so we could share in his divine life, but it is more. It is primarily an act of worship, a gift to the Father! In fact, it is the fulfillment of all the Old Testament sacrificial worship. We could say it is the one true act of worship ever offered by humanity because it is the perfect gift of self to the Father of the Divine Son. This is why Christ’s death signifies the destruction of the Old Testament worship. When Christ cleansed the temple he was asked by what authority he did so; he said, “Destroy this temple and in three days I will raise it up.” And, St. John tells us, “But he was speaking about the temple of his body” (Jn 2:19, 21). His body is the place of true worship—the new temple. This is also why when Christ dies on the Cross the temple curtain is torn in two. The old worship of the old temple is over: Jesus has fulfilled all worship of the Father with the gift of his life on the Cross.

Listen to how St. John Paul II describes the Cross, the Eucharist, and this true worship:

By virtue of its close relationship to the sacrifice of Golgotha, the Eucharist is a sacrifice in the strict sense, and not only in a general way, as if it were simply a matter of Christ's offering himself to the faithful as their spiritual food. The gift of his love and obedience to the point of giving his life (cf. Jn 10:17–18) is in the first place a gift to his Father. . . . “A sacrifice that the Father accepted, giving, in return for this total self-giving by his Son, who ‘became obedient unto death’ (Phil 2:8), his own paternal gift, that is to say the grant of new immortal life in the resurrection.”[6]

Lessons from Our Lady at the Foot of the Cross

Why does Christ make his sacrificial death present in the Mass? So that we can join in it. To understand this, let us ask a question: What is Our Lady doing at the foot of the Cross? Why is she present there? What does she see? What is happening in her heart? At Calvary, many people were there as spectators, some were there only to mock. Very few there knew what was going on—that Jesus was offering his life for the salvation of the world. Mary was not there as a spectator. No, she was actively participating, she was offering her own life with his. She could see the sacrament. She could see what was going on invisibly behind the visible reality. This was not the death of a common criminal. She offered herself with him; she died, too, by consenting to his death, which is why the early Fathers of the Church said she suffered martyrdom. In fact, if the Cross is a marriage between God and man as the Fathers of the Church claim, then Mary was there representing all of us. She was the Bride, giving consent to this marriage. This is why she is coredemptrix—not in the sense of being equal in the work of our redemption but in how she cooperated in this work. By her yes at Calvary, by her uniting herself to Christ in his self-gift, she was becoming the Mother of all the redeemed.

The question we should ask ourselves is: How am I present at Mass? Am I there as a spectator, a distracted bystander? Am I there only to get something? Or am I like Mary, learning to make a gift of myself, saying yes to his sacrifice with my own life, offering myself with Christ on the altar for the salvation of the world? Mary was exercising her royal priesthood in which all Christians share at the foot of the Cross, making a gift of herself united with the one sacrifice of her son.

A lot is made of what Vatican II said about fully conscious and active participation. What is active participation? Pope Benedict points out that this is not to be understood in an external way. Active participation is not simply doing external things—kneeling, sitting, singing, nor even serving as a lector at mass. Active participation is primarily interior. Pope Benedict XVI said, “The active participation called for by the Council must be understood in more substantial terms, on the basis of a greater awareness of the mystery being celebrated and its relationship to daily life.”[7] The conciliar Constitution Sacrosanctum Concilium encouraged the faithful to take part in the eucharistic liturgy not “as strangers or silent spectators,” but as participants “in the sacred action conscious of what they are doing, with devotion and full collaboration.”[8] This exhortation has lost none of its force. The Council went on to say that the faithful “should be instructed by God's word and be nourished at the table of the Lord's body; they should give thanks to God; by offering the Immaculate Victim, not only through the hands of the priest, but also with him, they should learn also to offer themselves; through Christ the Mediator, they should be drawn day by day into ever more perfect union with God and with each other.”[9]

To truly participate in the Eucharist, we must be like Mary. We must be aware of the mystery being celebrated. Here on this altar Christ is pouring out his life. We must then take that mystery into our daily lives. I must allow this reality to transform all my actions so that my life too can become a gift, an offering, through him, with him, in him. I must learn to offer my life with Christ, as Mary did at the foot of the Cross.

The Transformation of Suffering

There is nothing I cannot transform into an act of love. This is the fundamental catechesis of the Eucharist that is meant to teach me how to live. As Vatican II said, through the Eucharist all “are thus invited and encouraged to offer themselves, their labors and all created things, together with him.”[10]

This teaching has the power to transform our whole lives—this is what the Eucharist wants to do. If I understand this teaching, even my most difficult sufferings can become a joy! Why? Because they are not empty and meaningless, just as Christ’s suffering was not empty and meaningless. All my sufferings can be brought here to the altar and laid upon it. Here they take on an infinite value. Christ unites my suffering with his and presents it as a gift to his Father. And then the Father gives his own gift: he gives me back Jesus. He strengthens me with the life of Jesus so that I can suffer out of love. “Now I rejoice in my sufferings for your sake, and in my flesh I am filling up what is lacking in the afflictions of Christ on behalf of his body, which is the church” (Col 1:24). What is lacking in Christ’s afflictions? Only that you and I are not sharing in them. Why does St. Paul rejoice? Because he knows that his imprisonment is a gift of love, and united to Christ’s sacrifice it is fruitful for the world.

This is the fulfillment of our lives. When we say that the Eucharist is the Source and Summit of our lives, this is the summit! Everything in our life, most especially our sufferings, can and should have a profound meaning. Because through the Eucharist, everything, large or small, can be part of the redemption of the world. As Pope Benedict says, “There is nothing authentically human—our thoughts and affections, our words and deeds—that does not find in the sacrament of the Eucharist the form it needs to be lived to the full.”[11]

Most Reverend Andrew Cozzens, S.T.D., D.D. is Bishop of Crookston (Minnesota) and Chair of the USCCB Committee on Evangelization and Catechesis.

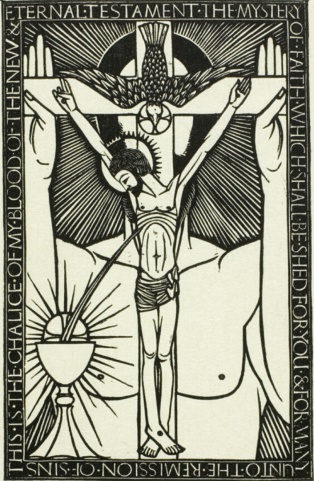

Photo credit: Eric Gill’s 1914 engraving of Mercy Seat Trinity, reprinted from The Sower, 33.1.

This article originally appeared on pages 7-9 of the printed edition.

Notes

[1] Anecdotally, we may have lost 20 percent of our more regular Churchgoers during the pandemic.

[2] Second Vatican Council, Presbyterorum Ordinis, 5.

[3] Second Vatican Council, Lumen Gentium, 11.

[4] Second Vatican Council, Gaudium et Spes, 24.

[5] Benedict XVI, Deus Caritas Est, 13.

[6] John Paul II, Ecclesia de Eucharistia, 13.

[7] Benedict XVI, Sacramentum Caritatis, 52.

[8] Second Vatican Council, Sacrosanctum Concilium, 48.

[9] Ibid., 48.

This article is from The Catechetical Review (Online Edition ISSN 2379-6324) and may be copied for catechetical purposes only. It may not be reprinted in another published work without the permission of The Catechetical Review by contacting [email protected]