Editor’s Reflections: The Church: Becoming What We Are

“About Jesus Christ and the Church, I simply know they’re just one thing, and we shouldn’t complicate the matter.”[i] These are the striking words of St. Joan of Arc, boldly spoken as she stood trial. “They’re just one thing” because Jesus himself described his relationship to the nascent Church as the relationship of vines united to a single branch (cf. Jn 15:1–5). In other words, while distinctions are not difficult to find between Christ and the Christians who make up the Church, at root (forgive my pun), they are one living thing.

We live in a time of heightened divisiveness and loneliness. Online social connections are, as we all know, meager substitutes for real connection and friendship. Perhaps you share with me the conviction that the Church is the needed antidote. The Church is—and at the same time is meant to become—a remarkable communion. The sacraments bring us into communion with the Blessed Trinity, and being in this communion means that we are also intimately united with everyone who is in this remarkable relationship with God: the angels, the saints, all those in Purgatory, and every baptized person on the planet. If Baptism makes us adopted sons and daughters of the Father, then it also makes us truly brother and sister to one another. This extraordinary truth arises out of what the sacraments accomplish.

Note

[i] Catechism of the Catholic Church, no. 795, quoting Acts of the Trial of Joan of Arc.

AD: Franciscan University—Celebrating 75 Years of Service to the Church

For more information about the celebrations for the University's 75th Anniversary, please go to 75.franciscan.edu. Or call (740) 283-3771.

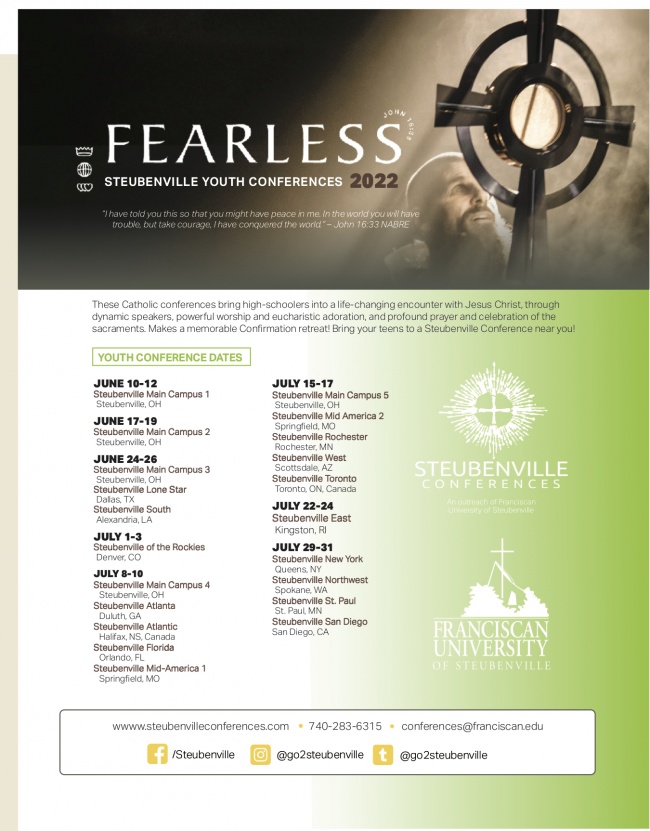

AD: FEARLESS! 2022 Steubenville Youth Conferences Schedule

For more information on the 2022 Steubenville Youth Conferences, go online at www.steubenvilleconferences.com or call 1-740-283-6315.

Editor's Reflections: The Spiritual Life and Our Missionary Potential

There have been some very good books written in the past few years centered on helping parishes to become mission-focused.

There have been some very good books written in the past few years centered on helping parishes to become mission-focused.

AD: Mark Your Calendar! Summer 2022 Steubenville Adult Conferences

To learn more about the Steubenville Adult Conferences, go to https://steubenvilleconferences.com/ Registration will open at the end of January 2022.

From the Shepherds: Community Life - in the Directory for Catechesis

Practices and Prayers of Catholic Bereavement

It’s strange to say it, but I love how we Catholics celebrate funerals. Even atheists walk away from our Masses of Christian Burial in awe. If only they (and likewise our own faithful people) could appreciate with greater fullness the rich spiritual heritage that surrounds Christian death!

It’s strange to say it, but I love how we Catholics celebrate funerals. Even atheists walk away from our Masses of Christian Burial in awe. If only they (and likewise our own faithful people) could appreciate with greater fullness the rich spiritual heritage that surrounds Christian death!

Unto Us a Child Is Born

Some people approve of “baby-worship;” others don’t. I’m one of the worshippers. Baptizing babies—the younger the better—is one of the greatest joys of my priesthood. I love to see and hear babies at Mass. They preach a far better sermon than I could ever do. By raising their voices in praise of God, they tell us that a mother has had a baby, and that her faith is so fundamental to her life that she wants to bring the child to Mass with her. Thank God for mothers and fathers and babies! On Christmas Day Our Lady and St. Joseph, the angels, and the shepherds all worship a baby, the baby. Of course, they worship him! This baby, this child born for us, this Son given to us, wrapped in swaddling clothes and lying in a manger, is God the Son, eternally begotten of the Father in the Godhead, and on Christmas day is born in time and human nature of the Ever-Virgin Mary. Of course, we must worship him!

Catholic Schools: The Incarnation – A Model of Perfect Inculturation

There have been many moments where, although I’m still relatively young, I have felt generations older than the students that I teach. Moments where I use a # next to a number and they get confused because they think it’s a social media hashtag. Moments where they teach me what words like “simp” and “sus” mean because I have never heard of them. Moments where I have to do a web search for what a VSCO Girl is because they keep saying it and I don’t want to appear naive. It’s all good fun and keeps me on my toes, but there is also a very real call from the Lord in these moments. As a teacher, Christ remains the model for all of my teaching; thus, I must imitate him in his incarnation.

The Impact of the Incarnation

To say that “the Word became flesh and dwelt among us” (Jn 1:14) carries great weight, particularly to an educator. The wonder of the Incarnation should impact every Catholic—the fact that God humbled himself to become like his lowly creation is an act of pure love that should astound us and draw us to love him more—but there is an even deeper calling for those of us working in the vineyard. We must imitate the example of inculturation that Jesus shows through the Incarnation. In this way, we are able to meet our students where they are, just as God met humanity by assuming our human nature and being born into the world in the same manner that every other human does. A mystery as infinitely great as God is not so easily comprehended by the human mind. By assuming our human nature, Jesus walks among us, like us in every way except sin, so that we cannot say that we have a great high priest who does not sympathize with our humanity (c.f. Heb 4:15).

Decolonizing the Curriculum in the Light of the Incarnation

On March 9, 2015, protests erupted among students of the University of Cape Town, South Africa under the slogan #RhodesMustFall. They demanded that the statue of British colonial-era politician and diamond magnate Cecil Rhodes be removed from a prominent place on their campus. The protest was given further impetus internationally by movements such as Black Lives Matter as well as reactions to widespread accusations of institutional racism. In addition to inspiring demands for other statues to be torn down or relocated—from Edward Colson in Bristol, England, to Hannah Duston in New Hampshire—the broader demands of the protest gave birth to an academic movement known as “Decolonizing the Curriculum.”

This term itself is contested and therefore difficult to define. For its supporters, Decolonizing the Curriculum (DtC) entails the balancing and broadening of the academic curriculum in schools and universities from an exclusively Western-centered canon of ideas and texts to include the philosophy, worldviews, and history of other cultures. For its skeptics, it is another front in a seemingly endless culture war, which may threaten to undermine the foundations of Western Christian civilization itself. As one of the most discussed issues in education today, it is timely for us who work in Catholic schools and universities to consider the issue in the light of our faith, despite the risk of controversy. In seeking a balanced way forward, reflection on the wonder of the Incarnation may provide a way out the impasse.