Inspired through Art: The Supper at Emmaus by Rembrandt Van Rijn, c. 1628

To view art click here.

Rembrandt’s painting, The Supper at Emmaus, conveys the awe and wonder of the revelation of Christ in The Eucharist. Here then are definitions of terms used in this article:

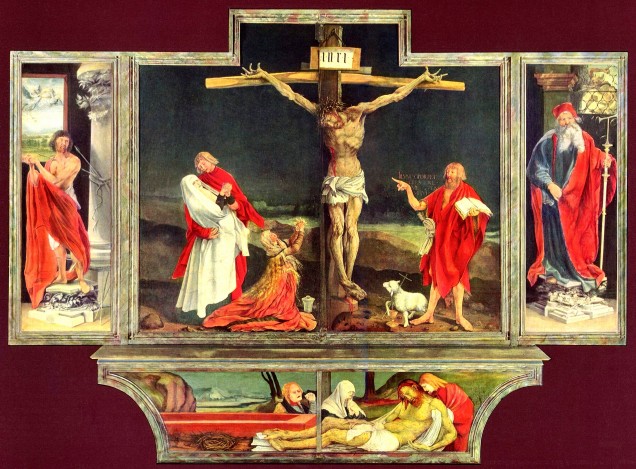

Inspired Through Art: The Isenheim Altarpiece by Matthias Grunewald, c. 1512

Click here to view artwork on smart board.

Inspired through Art: The Baptism of Christ by Pietro Perugino, c. 1497

To view this image on a smart board click here. In this instance, you'll may need to "Save image to Downloads" in order to enlarge the image on your smart board. It depends on your web browser.

Learning through Art: Rembrandt's Holy Family

Worksheet for studying Rembrandt's Holy Family painting.

Art Notes: The Holy Family by Rembrandt

The Gospel tells us clearly that Jesus Christ is both true God and true Man. Meditating on this Mystery, the Fathers of the Church concluded that the Blessed Virgin Mary must in some sense be Mother of God, and from the time of Origen (185-254 AD), the Virgin Mary was known as ‘theotokos’ or ‘God Bearer.’

In 429 this title was challenged by Nestorius, who held that Mary was the mother only of Christ’s humanity, and he coined the term ‘Christotokos’ or ‘Christ Bearer’ to describe her role in salvation history. Led by St Cyril of Alexandria, the Councils of Ephesus (431) and Chalcedon (451) rejected the teaching of Nestorius, pointing out that Christ’s human and divine natures were both fully present as a hypostatic union in the one Person of Christ. As mother of Jesus, Mary was therefore mother not only of Christ’s human nature, but also in a real sense of his divine nature. The Virgin’s title of ‘theotokos’ has never subsequently been theologically disputed.

In the Latin Church, the title was translated from the Greek as ‘Dei Genetrix’, ‘Mother of god’, and in this issue we will examine the way in which the great Dutch painter, Rembrandt, interpreted the idea of Mary as ‘ Mother of God’. The painting to be studied is his Holy Family, made in 1645, and presently hanging in the Hermitage Museum in St. Petersburg.

Learning through Art: The Entombment of Christ

Here is a downloadable worksheet that may be photocopied for catechetical purposes.

Art Notes: The Entombment of Christ

While one often learns about a person’s character from letters with friends and biographies written by contemporaries, much of Caravaggio’s life is known only from police records. Michelangelo Merisi, better known as Caravaggio after his small Italian birthplace, was born a week before the naval Battle of Lepanto in 1571 when Muslim invaders were driven out of Christendom. Orphaned by age 13, when the Bubonic Plague had claimed every member of his family, he became a wanderer on the streets, searching for purpose. The painter traded his fair share of threats and insults, smashed plates in restaurants, and often found himself in a squabble with gangs and vagabonds he encountered. Some say the man slept in his clothes with a dagger at hand. Yet he clearly possessed a fascination with the transcendent, the Christian mystery in particular, as seen in his paintings depicting the life of Christ and his apostles. The sacred and the profane shared an intimate dance in Caravaggio’s life and in his artwork.

The Entombment of Christ was originally painted as the altarpiece of the Chiesa Nuova, St. Philip Neri's church in Rome. This 17th century masterpiece serves as a dramatic depiction of human grief and sorrow, yet an equally poignant reminder of human hope in everlasting life. Notice that there is no background, no landscape or cityscape to catch your eye, but rather the artist longs to draw you into the scene at the front, using a type of spotlight effect. It seems that Caravaggio is depicting on canvas through his tenebroso what the evangelist St. John writes so eloquently: “The light shines in the darkness and the darkness has not overcome it” (1:5).

Learning through Art: The Agony in the Garden by Andrea Mantegna

Use the questions and comments on these two pages as a study guide of The Agony in the Garden by Mantegna.

Suggested uses: First Communion, First Confession, Lent, Exploring the Mass, Confirmation, RCIC

1. Find the three groups of people (and angels) and describe what they are doing.

What are the Angels doing?

What are the Apostles doing?

What are the Roman soldiers doing?

Art Notes: The Agony in the Garden

Andrea Mantegna painted ‘The Agony in the Garden’ on a wood panel using egg tempera (around 1458-1460), and it measures 25” by 32” (63 x80 cms). It is, therefore, too large to be part of a predella and too small to be an altarpiece, so it is most likely that it was painted for private devotion. Mantegna’s brother-in-law, Giovanni Bellini, painted an ‘Agony in the Garden’ in 1465, and the two paintings hang on the same wall of Room 62 in the National Gallery in London.

All his life Mantegna was interested in rocks and ruins and then studied them intensively. This fascination is manifested in the structure of the painting. Christ is shown centrally, kneeling in prayer on a rock formation which clearly represents and altar. This tells us that the episode in the Garden of Gethsemane is part of the Passover sacrifice which begins in the Upper Room and continues towards Calvary on the morrow.

Learning Through Art: The Crucifixion by Raphael

In this issue of The Sower, Learning through Art provides work sheets to help subscribers analyze and meditate upon the "Mond Crucifixion" by Raphael. In a particular way, Learning through Art focuses on how the painting illustrates the Mass as much as it does the Crucifixion. Highlighting its Contrasts and Harmony, Caroline Farey shows how the painting depicts Time and Eternity, Death and Life, Heaven and Earth.