Inspired Through Art: Anastasis by Fr. Tomas Labanic, 2006

“We are a people of the Resurrection.”

These words of St. Augustine, echoed in more recent times by St. John Paul II, call us to live in the hope and joy of Christ’s victory over death. Even in times of suffering, spiritual aridity, or simply the humdrum of everyday life, we have the glorious light of truth to live by: Jesus has redeemed us through his Passion, and we will live forever.

The icon of the Resurrection helps unfold the unfathomable mystery of Christ’s victory over death. In the Eastern tradition, the icon of the Resurrection (in Greek Anastasis) is called the Icon of the Descent, which may at first not seem logical. If we are celebrating Jesus having risen from the dead, why look at his descent to the dead?

Certainly, in the Western tradition we are accustomed to images of Christ triumphantly stepping up out of the tomb, or rising above the astonished guards in a burst of light. These images fit in well with our understanding of the narrative. So then why the Descent?

One simple explanation is this: the exact moment of Christ’s Resurrection is not recorded in Scripture. There were in fact no eyewitnesses; it was an event hidden from human senses. Whereas, precise and numerous details of Jesus’ crucifixion are recorded by the Gospel writers, the details of his Resurrection are not.

...

As Jesus victoriously steps over the destroyed gate of hell, he pulls Adam and Eve from their tombs by the wrists; they were the first to sin and now are the first to be brought from the depths of the underworld. As the iconographer Fr. Tomas Labanic describes the two, “They are represented as old because the human race is old. They are clothed because they still represent their state of sin in paradise, in which they recognized they were naked after committing the sin, and went to cover themselves.”

Inspired Through Art: The Rest on the Flight to Egypt— Caravaggio, 1597

Journeying with the Holy Family

In the difficult journeys of human life, we must hope for a way to find consolation amid hardships. That means something different than a weekend away from the workplace or a summer vacation at the beach. The true rest we seek is that which is provided only from a source that transcends nature and suspends time and space, even if for a brief moment. That source is the supernatural grace of God.

In the earthly journey of Jesus, a particularly harsh event took place very early in life, which challenged Mary his mother and St. Joseph.

In 1597, Michelangelo da Merisi da Caravaggio, or simply Caravaggio, painted The Rest on the Flight to Egypt. Images that show events on the journey are non-canonical; the Scriptures do not recount specifics of the travels of the Holy Family prompted by Herod’s massacre of the Holy Innocents, the killing of those male children born near in time to the birth of Jesus. Matthew 2:14 simply recounts that they “..departed for Egypt.” In the Early Renaissance, apocryphal accounts appeared that told of an imagined setting with a variety of additional elements, like Joseph knocking down chestnuts, Mary breastfeeding Jesus, or date palms bending low to provide food for the travelers. Following the tradition for this type of image, we might expect some examples of something to eat in Caravaggio’s painting, but we see no nuts or fruit. Behind Mary, some shadowy brambles and thorns are a reminder of the harshness of the wilderness. However, in appreciation of God’s providence in nature, the artist has added something nutritious: the oak tree behind Mary contains a blooming array of mushrooms; but the subject of this image goes beyond food. Caravaggio took the story in a completely supernatural dimension by adding unique elements unlike any of his predecessors.

Inspired Through Art: The Virgin of the Rocks

This mysterious painting by Leonardo depicts a non-biblical meeting between Our Lady, the Christ Child, and an angel with St. John the Baptist in a rocky grotto. It is the second version of a painting originally commissioned in 1483 to be the central panel of a large altarpiece for the Franciscan Confraternity of the Immaculate Conception in Milan, Italy. While the subject of the Madonna and Child with an infant St. John the Baptist was celebrated throughout the Renaissance, the presence of St. John in this particular setting makes the inspiration for the painting difficult to assess. Though the infant St. John is not recorded as being present in Scripture, Leonardo’s version could possibly be following a medieval tradition of portraying the Holy Family during their flight into Egypt, hence the rock-strewn landscape. While the exact source of the narrative is uncertain, the painting’s rich iconography and harmonious design contain a wealth of meaning. In addition, the unique method of observation Leonardo has employed to the scene sets the painting apart from other artists’ interpretations of the theme.

An Extraordinary Scene

Our Lord is sitting on the ground supported by an angel. The position of Mary’s hand above the Infant’s head as well as her drooping cloak, which stops just short of his extended right hand, produce a vertical movement within the composition that stresses the Christ Child’s importance. Both Christ and the angel look in the direction of St. John; a silent dialogue we are blessed to witness. The environment around them serves to reinforce their otherworldliness. Clark adds, “Like deep notes in the accompaniment of a serious theme the rocks of the background sustain the composition, and give it the resonance of a cathedral.”[9] The fantastical nature of this “cathedral” of caverns points to the profound mystery of the beings in this drama. It is not strange for its own sake; rather it heightens our awareness of the supernatural. The rocks themselves are standard symbols of Christ. Revisiting Ferguson, this attribute “is derived from the story of Moses, who smote the rock from which a spring burst forth to refresh his people. Christ is often referred to as a rock from which flow the pure rivers of the gospel.”[10] The cool body of water in the background recedes into a far-off misty mountain scene not unlike a landscape one would find in J.R.R. Tolkien’s Middle Earth. Leonardo’s imagination seemed to know no bounds.

It was an imagination informed by his relentless investigation of the natural world. To heighten the aforementioned three-dimensionality of the painting, Leonardo incorporates his perceptive studies of light, shade, and perspective. These studies can be read in the publication of his numerous notebooks. He writes, “Painting is concerned with all the ten attributes of sight: darkness and light, solidity and color, form and position, distance and nearness, motion and rest.”[11] This painting contains all of these elements. When the results of Leonardo’s explorations into sight and of the natural world are united with religious subject matter, the effect is a true masterpiece of sacred art.

Inspired Through Art: The Meeting of St. Anthony and St. Paul – Sano di Pietro

How important is spiritual brotherhood? For those who are called to the ascetic life, either in a specific monastic order or in a “Benedict Option” community in a neighborhood, the consolation of fellowship with others who share your faith can be a vitally important spiritual aid. For St. Anthony the Abbot, his pilgrimage journey to find St. Paul of Thebes is a story of looking for a brother.

St. Anthony’s Journey

This image is one of several panel paintings that illustrate episodes from the life of St. Anthony, who is considered to be one of the founders of desert monasticism: the ascetic movement that began in the Egyptian desert in the 3rd century. Following the biographies of the saint by St. Athanasius and St. Jerome, this image recounts his journey to meet another hermit, St. Paul of Thebes. According to the story, St. Anthony was given knowledge of St. Paul by a heavenly message that told him there was someone who was as an ascetic like himself who had entered the desert even earlier than he. St. Anthony, wanting to see and know him, set out to find him. According to some versions, the human element of vainglory motivated St. Anthony; he wanted to disprove that someone else had actually originated the eremitic— or “desert inhabiting”—vocation. Along the way he experiences unusual challenges, which the collected stories identify as creatures who confront, tempt, or sometimes assist him.

Sano di Pietro of Siena

While there is debate over the attribution, it is certain that this painting was created by a Sienese artist in the early 15th century. Recent scholarship attributes the image to Sano di Pietro, also known as the “Master of the Osservanza,” the title coming from the masterwork, the Osservanza Altarpiece in Siena. Previously, this painting was attributed to Sassetta, a more prominent Sienese painter from that period. The Sienese school in the 15th century held onto the late Gothic style of icon-like depictions, with great attention to isolated details with no interest in the scientific depiction of true perspective space that was being developed in the Florentine Renaissance at this time. The powerful element of naturalism, which makes Renaissance and contemporary realism so convincing, is not to be found in this painting. However, this artist bends time and space toward a perception that goes beyond what a photographic depiction could ever portray.

Continuous Narrative

The painting relies on continuous narrative to depict a timeline of separate events all in one painting. This pictorial device has numerous examples from this time period. The most famous is The Tribute Money by the Florentine, Masaccio, who shows the scenes from Matthew 17:24-27, where St. Peter is first instructed by Jesus to go to the lake and catch a fish, then to pull a coin from its mouth to pay the temple tax tribute. Then the viewer’s attention shifts to Peter catching the fish at the edge of the water, then to Peter handing the money to the Roman official. All of these separate bits of the story occur in one continuous space, so we see St. Peter three times. This device was also used by Sano di Pietro to show St. Anthony setting off on his journey, then encountering a centaur at the edge of a forest, then finally arriving and embracing St. Paul. This way of showing time passing has a practical element: show three events but paint just one picture. However, the practical element is surpassed by the psychological effect of condensing the literal timeline into a flowing whole where the viewer’s eye moves the clock.

Inspired Through Art: Mary, Queen of Heaven and the Blessed Trinity

Master of the St. Lucy Legend, c. 1485/1500

"The ultimate end of the whole divine economy is the entry of God’s creatures into the perfect unity of the Blessed Trinity…even now we are called to be a dwelling for the Most Holy Trinity,” teaches the Catechism of the Catholic Church. (Par. 260)

The one creature who most uniquely entered into the perfect unity of the Blessed Trinity was the Blessed Virgin Mary, Mother of God. From the moment of her Immaculate Conception to her Assumption and Coronation as Queen of Heaven, Mary was the pure and sinless dwelling of the Most Holy Trinity. An exquisite 15th century painting from the National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC, titled Mary, Queen of Heaven, invites us to contemplate the unique and intimate relationship of the Mother of God to the Blessed Trinity. The beautiful image also invites us to imitate Mary, so we may grow in communion with each of the Divine Persons of the Blessed Trinity as she did.

Queen of Heaven, Rejoice! Alleluia!

One of the traditional Marian antiphons for the Easter season is the beautiful exclamation, Queen of Heaven, Rejoice! Alleluia! In this large panel painting we have the perfect image to accompany that Easter hymn of praise to Mary.

For we see the Blessed Virgin Mary at the center of the composition, clothed in gold trimmed robes of red and dark blue. Mary’s serene oval face is framed by delicate locks of wavy hair, and her hands are folded in a gesture of prayer and contemplation of the mystery of her divine Son. The panel is the work of an artist known simply as the Master of the Saint Lucy Legend, because his most famous work—an altarpiece from 1480—showed episodes from the life of Saint Lucy. In this masterpiece, the artist captures three aspects of Marian theology in a single painting of intense color, remarkable movement, and ornate texture: first, the Assumption of Mary; second, her Immaculate Conception signified by the crescent moon under her feet; and third, her Coronation as Queen of Heaven.

Inspired Through Art: After First Communion by Carl Frithjof Smith, 1892

Norwegian painter, Carl Frithjof Smith, is not a well-known artist today. Despite his lack of fame, his art is beautiful and worthy of recognition and study. Smith lived and worked for all of his adult life in Germany, until his death in 1917. After studying at the then thriving Academy of Fine Art in Munich, Smith took a teaching position in Weimer, Germany, where he remained for most of his life. His work consists mainly of portraits and genre paintings.

Genre painting explores the sphere of a person’s ordinary activity. Focusing on scenes from daily life, these works delve into human interactions, often enticing us to examine our own everyday moments in a more thoughtful manner. The genre painter must be someone in touch with the inner psyche of others. In what is perhaps his most famous work, After First Communion, Smith triumphs at this craft, presenting a scene that is rich in human feeling and meaning.

In the painting we see Mass participants spilling out of a church door on the left, down steps, and onto the street. This crowd consists mainly of young girls. What is most striking about this painting is the dazzling white of the girls’ ceremonial dresses. Worn at baptism, first Eucharist, and marriage, white garments symbolize the purified soul of the believer. The gray stone of the church contrasts with the vibrant white of the girls’ garments. There is an ethereal feel to the work that is anchored by the darker tones of the church and the garments of fellow parishioners. Smith balances the careful study of figures with a soft atmospheric treatment of the subject matter. This interplay is particularly clear in his treatment of the background compared to the foreground. The subject matter is clear and well described, and the use of contrast is greater in the foreground, while soft colors and brushstrokes are used in the background. His art is considered to be a middle way between rigid academism and airy plein air painting. While the general feel of the painting is lovely and pleasant, the expressions and interactions of the subjects are what draw us deeper into the work.

Inspired Through Art: The Annunciation Piero della Francesca, 1452

How does God make order and beauty in the world, and show it to us? Along with glorious sunsets and colorful flowers, there are other ways to know God as the Creator of beauty. In the apparently invisible realm of mathematics, he is not silent; rather he conveys his order and mystery in mathematical forms, contemplated and understood as meaningful and expressive of his Divine Mind. Hidden in plain sight, those embedded forms can be seen inside of nature in things like symmetries, tessellations, crystals, and plant growth patterns. Those forms can also be incarnated in artwork, which is an area of creative interest for some artists. One of those artists is Piero della Francesca.

Piero della Francesca (1415-1492) was an Italian Early Renaissance painter recognized as an artist with an interest in both religious art and mathematics. He was born into a noble family in Sansepolcro (modern-day Tuscany). After an apprenticeship, he became familiar with the art of some of the highly regarded artists of the day: Masaccio, Donatello, Fra Angelico, Brunelleschi, and others. Piero is known not only as a Renaissance artist but also an authority on mathematics, writing books on geometry, perspective, and proportion. Mathematics and proportion have been embedded in architectural ornamentation since Vitruvius, the ancient Roman architect. Sacred artists and designers made use of much of this knowledge throughout the Middle Ages. The interest in a “Divine Proportion” heated up in the time of the Renaissance when Luca Pacioli, an Italian mathematician and Franciscan friar, wrote his treatise titled On the Divine Proportion, and had it illustrated by his student, Leonardo da Vinci. Pacioli had been a student of Piero della Francesca and developed ideas he gained from Piero, especially those which deals with proportion and proportionality.

Inspired Through Art: The Art of Discernment in Catechetical Ministry

Finally, I realized that love includes every vocation, that love is all things, that love is eternal, reaching down through the ages and stretching to the utmost limits of the earth. – Saint Thérèse of Lisieux

Catechetical ministry involves ongoing discernment of God’s loving initiative and the human response of faith to God who reveals. This dimension of catechetical activity is brought to life in an exquisite masterpiece painting titled, Woman Holding a Balance, by the 17th century Dutch master artist Johannes Vermeer. Completed in 1664, this evocative work offers a visual meditation on the art of discernment in catechesis and in the spiritual life.

Much of Vermeer’s artistic creativity was focused on genre paintings of close domestic scenes infused with extraordinary spiritual depth. His masterful handling of light and refined compositions draw forth hidden spiritual realities radiating from the calm household scenes, gentle figures, and delicate colors emanating from his remarkable canvases.

Inspired Through Art: The Holy Women at the Tomb

William-Adolphe Bouguereau’s work consists of over 800 paintings and focuses on classical and religious subject matter. We can appreciate his mastery of technique in this painting of “The Holy Women at the Tomb,” set on the morning of Christ’s resurrection. It illustrates well the mystery of the resurrection and is a window into the first announcement of Christ’s triumph over the grave. We will use this work to dive deeper into this particular scene and explain how the composition creates a contrast between death and life.

This scene depicts four figures, three women and an angel, completed in the Realist style. We will focus on Mark’s account of the resurrection, since his Gospel names three specific women who went to the tomb the morning of Christ’s resurrection. The Gospel writer tells us these women are, “Mary Mag′dalene, and Mary the mother of James, and Salo′me” (Mk 16:1). Just three days prior, they must have experienced immeasurable distress as they witnessed Christ’s passion and death by crucifixion. Their dark clothing and expressions marked by grief illustrate the toll of his death upon them.

The event depicted in the painting takes place on the Sunday morning after the Sabbath, following Christ’s crucifixion and hurried burial, which was due to the approaching Sabbath. Jewish custom would have prevented any of Jesus’ followers from tending to his body on the Sabbath. Therefore, these women returned to Christ’s tomb to anoint his body at the first permissible moment. The Gospel tells us, “And very early on the first day of the week they went to the tomb when the sun had risen” (Mk 16:2). The rising sun can be interpreted as a symbol of hope. The morning sun has also been interpreted as a symbol of rebirth by many past cultures. It seems to foreshadow what the women will encounter.

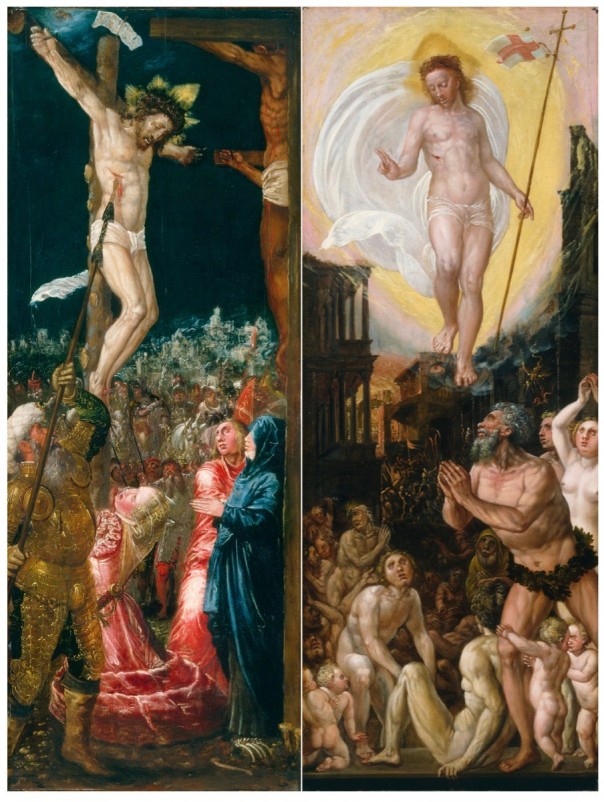

Inspired Through Art: The Crucifixion and The Harrowing of Hell

To view "The Crucifixion" image, click here; then click on the download button, then on the double underscore symbol to download a high resolution version for your smart board.