There can be no greater sign of hope than the expectant mother. She is the “one who waits” for the pain and joy of childbirth. She affirms the strength of womanhood, cherishing the living hope slowly taking form in her womb, or “beneath her heart” as St. John Paul II put it in Evangelium Vitae.

Therefore, the Church sets a unique pregnant woman before us. In this issue of The Catechetical Review, focused as it is on Christ our Hope, let us turn our gaze to the one who points us all towards the Coming of the Christ through the great sign of hope: Mary Immaculate.

Mary is rarely presented in Christian art as a pregnant woman, that is, until you look closely at one of the most widely reproduced Marian images, the holy Virgin of Guadalupe. This unusual image was miraculously printed on the cloak of the poor man, St. Juan Diego, in 1531. It is the central object of devotion in the most visited Marian shrine on our planet, where Mass is celebrated each day, for twelve hours on the hour! To see Mary’s image in this basilica, you get on a moving walkway, such as is found at airports, and you glide past, amidst a continuously gazing crowd. Better to step back and look more carefully at the simplicity and mystery of this female figure.

Here is a strong young woman, of Aztec countenance and slight stature. Her head is inclined in humility, her fingers gently joined. At first sight it is a typical representation of the Immaculate Conception, but here Mary is pregnant (as indicated by the black sash). In the same era, St. John of the Cross marvelled at this mysterious pregnancy:

With the divine Word made pregnant,

the Virgin walks this way,

would that you might let her stay with you.

Chapter seven of the Book of Revelation presents the same image: the pregnant woman is a “great sign in heaven.” She is clothed in the sun, crowned with stars, the moon beneath her feet, but there is a paradox here. How is the celestial queen of the Book of Revelation the same person as the obscure village maiden of the Gospel infancy narratives?

We turn to one of those narratives for the key. Luke tells us that this maiden—perhaps only sixteen years old—was hailed by her older cousin as “the mother of my Lord” (Lk. 1:43). That is a royal title reserved for the “queen mother,” the king’s mother who ranked first after the king in the royal families of the Middle East in the time of Christ.

This royal title affirms that this maiden is the human being on whom all history is poised. Through her, the Messiah King will come to save his people. His reign depends on the consent of this young Jewish woman, who lives in an obscure village in a remote province of the Roman Empire, a virgin chosen to be the mother of the Messiah, an honor for which all Jewish women would long.

The royal responsibility of Mary brings joy: “Blessed are you among woman, and blessed is the fruit of your womb,” cries her cousin. It also brings pain: “and a sword will pierce your heart,” predicts the Temple prophet. If John the Baptist must offer his life to “prepare the way” for Jesus the Messiah, the chosen Mother must endure another martyrdom to complete his journey.

At the cross, Mary (the second Eve) will take her stand with the second Adam, Jesus her Son. Together they will be united in a healing work of obedience at the new tree of life.

The fruit of the new order of Jesus and Mary is justice. Mary’s song is the cry of the hope of poor women: “…the almighty has done great things for me.” She sings a song of justice for the poor: the rich and powerful humbled, the poor and hungry fed, the just reign of the true Messiah is coming!

Oppressed by Spanish conquest and impoverished under colonial rule, the indigenous people of Mexico recognized the pregnant Virgin of Guadalupe as their sister. She raised them up, called them to faith, and brought about a new spirit of reconciliation in a turbulent colonial era, as people of all races and classes came together at her shrine. May we too find reconciliation in the Immaculate Virgin. May she bring the hope of the new life in her womb to our “sterile” society, and reconciliation and justice to wipe away our indifference and complacency.

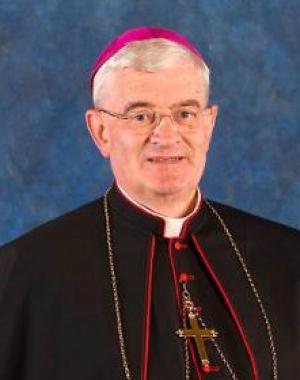

Bishop Peter J. Elliott is auxiliary bishop of the Archdiocese of Melbourne, Australia. In 2015 Bishop Elliott was appointed Episcopal Vicar for Religious Education. He continues his theological oversight of To Know, Worship and Love, the Archdiocesan Religious Education Texts.

This article was orginally on page 11 of the printed issue.

This article is from The Catechetical Review (Online Edition ISSN 2379-6324) and may be copied for catechetical purposes only. It may not be reprinted in another published work without the permission of The Catechetical Review by contacting [email protected]