Catholic Schools: The Paschal Mystery Time Machine – Teaching Time to Teens

What do the films A Wrinkle in Time, Back to the Future, The Terminator, Interstellar, and Avengers: End Game have in common? They all tap into our innate fascination with time travel. If you could travel through time, where in history would you go? Who would you visit? What would you alter for the sake of the future?

These are strategic questions I use to open the lesson on the sanctification of time. With this exercise, students are first invited into the time machine of their own memory and imagination. After this discussion, I pre-teach some basic doctrinal points about time:

- Time is created by God with a beginning and an end.

- Chronos time is time that we can measure and keep track of with calendars and clocks.

- Kairos time is time from God’s point of view. It is all of time at once in one “eternal now.” Eternity.

- The Eastern concept of time is cyclical. This is how beliefs such as karma and reincarnation emerged.

- The Western concept of time is linear and it has a telos or an end. It is progressing toward the future.

- We can think of the liturgical year as a spiral that is simultaneously cyclical and linear or advancing toward an end.

- Jesus, the Eternal Word, is timeless. (CCC 525)

- The Paschal Mystery changes how we experience time.

The fourfold event of Jesus’ Suffering, Death, Resurrection, and Ascension was so impactful and powerful that it reverberates through time in every direction. It hit history so hard that it broke it in two; that which came before Christ (BC) and that which began with Christ (AD). In the Old Testament, the Paschal Mystery is prefigured through typology and prophecy. In the age of the Church, it is echoed forward in the liturgical calendar. In the sacraments, the Paschal Mystery transcends time. The sacraments are, in a way, the only known means of time travel. When we remember our story and enter into it in the sacraments, we are entering into a dimension of time that is not stuck in the past, present, or future, but envelopes all of it. This is because, unlike any other religious figure, Jesus is not just a person of history. He is alive and actively encountering his people with his life-giving, saving love.

Inspired Through Art: Living the Mysteries of Christ in the Mysteries of Mary

“Mary does bring us closer to Christ; she does lead us to him provided that we live her mystery in Christ,” wrote St. John Paul II.[1] Throughout the year, the Church offers the faithful countless spiritual paths to live in the mystery of Christ through the feasts and fasts, the seasons and rhythms of the liturgical year. Manifold dimensions of the Paschal Mystery of Jesus’ Life, Passion, Death, and Resurrection unfold in time across the liturgical year. In this way, each day of the liturgical calendar is a renewed opportunity to enter into the life of grace and communion with the Blessed Trinity, who permeates time through the liturgical year to sanctify and transfigure human history.

The Catechism of the Catholic Church notes, “In celebrating this annual cycle of the mysteries of Christ, Holy Church honors the Blessed Mary, Mother of God, with a special love. She is inseparably linked with the saving work of her Son. In her the Church admires and exalts the most excellent fruit of redemption and joyfully contemplates, as in a faultless image, that which she herself desires and hopes wholly to be.”[2]

Contemplation of the mysteries of the life of the Blessed Virgin Mary lead the faithful into contemplation of the mystery of Jesus Christ, her divine Son. A beautiful Netherlandish altarpiece, titled The Fifteen Mysteries and the Virgin of the Rosary, places before our eyes the life of Jesus Christ and his mother Mary so we might imitate her example and experience her spiritual motherhood of the Church. The masterpiece image also invites us to renewed devotion to the Marian prayer of the Rosary, as the Church celebrates the Memorial of Our Lady of the Rosary each year on the seventh of October.

Encountering God in Catechesis: A Spirit-Led Classroom

To the surprise of my friends and family, I love being a middle school teacher. While admiring my enthusiasm, most people picture a hectic classroom filled with rowdy youth. It is true, some days I swear my students are on their second cup of coffee by first period. I have learned to enjoy these days because underneath all of that energy rests a deep desire to encounter Christ. In their fast-paced culture, young people’s hearts crave moments of silence, peace, and union with Jesus. When I first started teaching, I wanted each middle schooler to learn how to pray and to begin their relationship with Christ, but my efforts were not bearing much fruit.

To the surprise of my friends and family, I love being a middle school teacher. While admiring my enthusiasm, most people picture a hectic classroom filled with rowdy youth. It is true, some days I swear my students are on their second cup of coffee by first period. I have learned to enjoy these days because underneath all of that energy rests a deep desire to encounter Christ. In their fast-paced culture, young people’s hearts crave moments of silence, peace, and union with Jesus. When I first started teaching, I wanted each middle schooler to learn how to pray and to begin their relationship with Christ, but my efforts were not bearing much fruit.

I was doing something wrong. I began by praying the Our Father and Hail Mary with each class. My students knew these prayers from elementary school and did not show much excitement for praying them. My solution was to further explain the biblical origin of these basic prayers. While doing this helped a little, I still knew most of my students were not encountering Christ. No matter how much time I spent explaining the Our Father or Hail Mary, my voice was always the loudest one in the room. Even after introducing other prayers, there was no noticeable change. Why did the Holy Spirit not seem present?

I prayed the words of Saint Paul, “Likewise the Spirit helps us in our weakness; for we do not know how to pray as we ought, but the Spirit himself intercedes for us with sighs too deep for words” (Rom 8:26). I needed the Spirit to teach my students to pray!

The Spiritual Life: Sacrifice – Path to Communion

Editor’s Note: The U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops has announced a three-year Eucharistic revival, to reawaken Catholics to the goodness, the beauty, and the truth of Jesus in the Eucharist. Each issue of the Catechetical Review, during the revival, will feature an article on the Eucharist, to empower our readers to make increasingly more meaningful contributions to the Eucharistic faith of those we teach. We hope you enjoy this article.

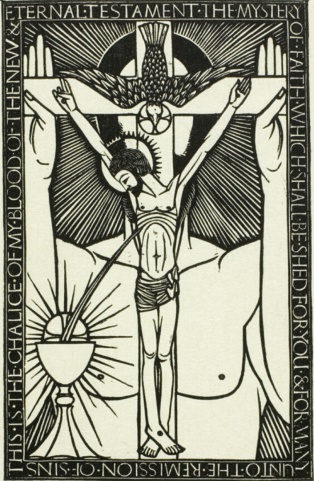

The great mystery of Christ’s sacrifice for us is at the heart of the Christian faith: “For Christ, our Paschal Lamb, has been sacrificed” (1 Cor 5:7). As the Catechism explains, Jesus’ death manifests his sacrifice in two ways:

Christ’s death is both the Paschal sacrifice that accomplishes the definitive redemption of men, through “the Lamb of God, who takes away the sin of the world,” and the sacrifice of the New Covenant, which restores man to communion with God by reconciling him to God through the “blood of the covenant, which was poured out for many for the forgiveness of sins.” (CCC 613)

Thus, the two principal effects of Christ’s sacrifice are, first, to remove our sins, and, second, to restore communion with God. Transformed by this gift of divine love, we are called to imitate Jesus and “walk in love, as Christ loved us and gave himself up for us, a fragrant offering and sacrifice to God” (Eph 5:2). Indeed, the Church teaches that every baptized Christian participates in Christ’s sacrifice (CCC 618). We are especially joined to it in the sacrament of the Eucharist, which makes Christ’s sacrifice ever present to us (CCC 1364). The Eucharist is a sacrifice because “it re-presents (makes present) the sacrifice of the cross, because it is its memorial and because it applies its fruit” to our lives by taking away our sins and restoring communion with God (CCC 1366).

The problem is that for most people today, the biblical notion of sacrifice seems obscure. What does sacrifice in general, and Christ’s sacrifice in particular, really mean? And how do the sacraments—especially Reconciliation and the Eucharist—manifest the Lord’s sacrifice?

The best way to gain insight into these questions is to consider the symbolism of the sacrifices in the Old Testament.

AD: Steubenville Parish Missions

To learn more or to schedule a Steubenville Parish Mission in your parish go to https://steubenvilleconferences.com/parish-missions/ or call 866-538-7426.

Viaticum: Sacred Food for the Final Journey

We never know which Holy Communion might be our last. We make a big deal of our First Communion, and rightly so. But why don’t we have a strong catechesis and spirituality of Viaticum, that final time we receive the Body of Christ before our soul leaves our own body to meet him?

As a Church, perhaps we are missing a robust eucharistic spirituality in general. Maybe we lack a proper sober focus on our preparation for death. We could likely all benefit from considering the Last Rites in a more personal and specific way, so that they may be more fruitfully celebrated for us and those we love.

For the Dying

“Father, you got here just in time,” the nurse says. It is such a blessed and needed relief when someone receives their final sacraments! No matter the circumstances, these gifts of Holy Mother Church provide occasions of intense grace, whether the person was a daily communicant or long fallen away, whether in an emergency situation or with the comfort of hospice care. Often people will seem to cling to life, whether consciously or not, and then decline rapidly after a priest’s visit. In my experience, this is particularly true if Confession was needed. Care should always be taken to arrange a private moment for that purpose to be properly disposed in the state of grace before the reception of the Eucharist.

Too often, the effects of medicine and the progression of illness limit the scope of the recipient’s participation. Especially with privacy law restrictions ever increasing, the faithful should be reminded to notify the parish with members’ serious health updates so they can be taken care of promptly. Our spiritual family has special solidarity with the suffering.

The texts of the ritual are of incomparable theological, poetic, and pastoral value. The Commendation of the Dying stands out among them with its litanies. Only in the most dire situations should these prayers be omitted. There is a unique form for the administration of Viaticum: “May the Lord Jesus Christ protect you and lead you to eternal life.” All this serves to heighten the gravity of this liturgical and human reality.

Receiving the Anointing of the Sick and Apostolic Pardon together with Viaticum is a sign of divine election. That monumental last blessing has sadly become a forgotten treasure of our spiritual patrimony. What certain peace a soul feels to experience the full force of the Church’s forgiving authority with a plenary indulgence to remit all temporal punishment due to sin in Purgatory, just when it is needed the most! The text is worth quoting in full: “Through the holy mysteries of our redemption may almighty God release you from all punishments in this life and in the life to come. May He open to you the gates of paradise and welcome you to everlasting joy. By the authority which the Apostolic See has given me, I grant you a full pardon and the remission of all your sins in the name of the Father, and of the Son, and of the Holy Spirit.”

The Spiritual Life: How the Eucharist Catechizes about the Meaning of Life

The United States Conference of Catholic Bishops is currently undertaking a Eucharistic revival.

The United States Conference of Catholic Bishops is currently undertaking a Eucharistic revival.

Falling in Love with the Church

Born into a Catholic family and baptized when I was sixteen days old, I grew up accepting the Church, receiving from her, but not understanding much about her identity.

Born into a Catholic family and baptized when I was sixteen days old, I grew up accepting the Church, receiving from her, but not understanding much about her identity.

More than a Birdbath: St. Francis of Assisi, a Living Instrument of Catechesis

Most people within the Catholic Church, as well as those who would consider themselves religiously unaffiliated, have some name and image recognition of St. Francis of Assisi. For many, the dominant image is the ubiquitous St. Francis birdbath nestled in the greenery or the flower garden. Others may think of Francis of Assisi’s particular love for the poor and the lepers of his day. For others, when they think of St. Francis, their consideration is drawn to the stigmata he received that resembled the wounds of the poor, crucified Christ.

These images all have a true connection to the man of Assisi, but there is one that often goes largely ignored: St. Francis of Assisi, the catechetical saint. The small yet substantive corpus of writings of Francis of Assisi reflect a powerful catechesis of the theology and spirituality of Catholic Christianity. Francis’ writings, mostly composed of prayers, letters, and Rules of Life for his followers, form a simple yet profound catechesis rooted in Scripture and expressive of the culture of Christendom in which Francis lived. In his writings, we are invited to meet a man who is described in an antiphon of the Liturgy of the Hours as a “thoroughly Catholic and apostolic man.” Francis was deeply rooted in the orthodox teaching of Catholic Christianity and committed to sharing this truth, which burned like a fire in his heart.

AD: Franciscan University—Celebrating 75 Years of Service to the Church

For more information about the celebrations for the University's 75th Anniversary, please go to 75.franciscan.edu. Or call (740) 283-3771.