Barbara Morgan: Inspiring Us with Maternal Hope

Few people impact us on such a deep level that it changes our life journey. For me, that influence happened in 1994. In August of that year, Barbara Morgan began the catechetics program at Franciscan University of Steubenville. I had the great blessing of being there when it started. She became a spiritual mother to me and infused in me a deep sense of purpose. In this article, I would like to share a few ways in which she did that with me.

The First Class

Barbara’s significance in my life was unparalleled, and I knew it would be profound as soon as I encountered her. At that first class, in the course entitled “Content and Curriculum,” I sat in the front, which is usually not the case for me (give me the back row, please). Since I showed up to the MA program with almost six years of parish youth ministry experience, I wanted to pay attention, since this course would be geared directly to pastoral situations. Little did I know what I was in for. As much as I loved the study of theology in all its disciplines, when Barbara began to teach catechetics, I was moved at a far greater level than any subject I had studied before. Through her, God revealed my vocation and identity to me and, as a result, I could never be the same person.

After her first class, I could not contain myself. I followed her to her office and had to tell her my plans for a teen Confirmation resource. I’m sure I sounded like a babbling fool. What was happening was not about my ideas regarding Confirmation; in a real way all my grandiose plans and projects were secondary. The underlying reason I had to seek her out was because I had had an unprecedented encounter with the Lord. I was reacting with unabated joy to a calling and could not contain myself.

And that was just the first class.

The Family of Mary at Her Presentation in the Temple

Who prepared the young heart and mind of Mary to respond to God in humble faith with a fiat, her yes to the Archangel Gabriel? Where did Mary, the Mother of God, learn to listen attentively to God’s word?

The beautiful painting The Presentation of the Virgin in the Temple, by Italian artist Andrea di Bartolo in the first decade of the fifteenth century, offers insight into Mary’s life through one pivotal moment in her youth. This event, of course, is known largely from early apocryphal writings. In this masterpiece, the Sienese artist brings to life, in vivid detail, the hidden moment that prepared Mary to take her unique place in God’s plan of salvation. Striking in its simplicity and beauty, this image draws us into the mystery of Mary’s life, a life that always leads to her divine Son, Jesus.

Full of Grace

“Hail Mary, full of grace!” These words of the Archangel Gabriel spoken at the Annunciation are familiar words of Christian prayer. They teach us an important truth about the Mother of God. Long before the Annunciation, Mary was filled with grace. From the moment of her Immaculate Conception, Mary was preserved from the stain of original sin. She was “full of grace” from her conception in the womb of St. Anne to her glorious assumption into heaven.

Andrea di Bartolo was commissioned to paint a large altarpiece dedicated to scenes from the life of the Blessed Virgin Mary. This panel was one of three small panels that depicted the domestic church in which Mary was raised. Two other panels show the birth of Mary and the generosity of her parents, St. Joachim and St. Anne, in their almsgiving and care of the poor. In this scene, the artist shows Mary at her presentation in the temple when she was consecrated to God within the devotion and faith of her family.

The Family of Mary

“The family is the basic cell of society. It is the cradle of life and love, the place in which the individual ‘is born’ and ‘grows.’”[1] These words of St. John Paul II remind us that the family has a fundamental and formative role, both in society and in the life of each person. This is true of every Christian, and it is exemplified in a special way in the life of Mary.

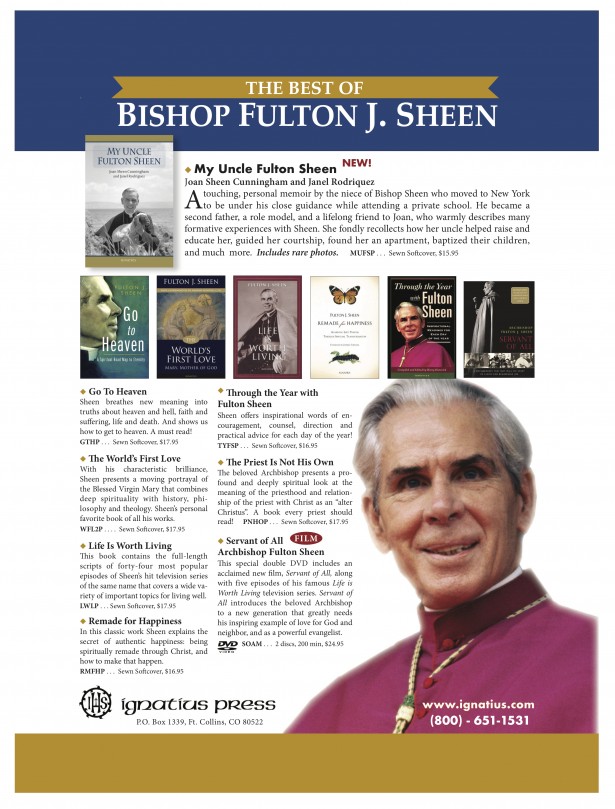

AD: The Best of Bishop Fulton Sheen Books & DVDs

To order any of these Bishop Fulton Sheen books or dvds, call 800-651-1531 or visit www.ignatius.com.

This is a paid advertisement and should not be viewed as an endorsement by the publisher.

Madeleine Delbrêl: The Missionary and the Church

By the time Venerable Madeleine Delbrêl was 20, she had converted to Catholicism from the strict atheism of her youth. Nine years later, in 1933, she was living as a missionary with two companions in Ivry, “the first Communist city and more or less the capital of Communism in France.” She decided to live in this community because she remembered the pain of not knowing God; her goal was not simply to evangelize them, but to befriend them. She lived there until she died in 1964.

Venerable Madeleine Delbrêl had an exceptional love for the Church and perceived that there was a profound link between Christ, the Church, and evangelization. “The work of the Church is the salvation of the world; the world cannot not be saved except by the Church.” In our current atmosphere of skepticism towards structures of authority and of the Church herself, she is a voice that reminds us how to love the Church, and how to bring Christ to the world in and through her.

Madeleine considered each person in the Church to be an essential part of the Church’s mission; there was no one who did not have a part to play. “We are not the Church unless we are the whole Church: each member belongs to the whole body.” Each person’s part was specific and vital: “And we are not the whole Church unless we are in precisely the place meant for us in the Church, which is the same as saying that we are precisely in our place in the world, where the Church is made present through us.”

These words are comforting and hopeful, but we always seem to struggle to find our purpose and direction. Delbrêl’s view is that we do not have to go crazy finding exotic projects: “Mission means doing the very work of Christ wherever we happen to be. We will not be the Church and salvation will not reach the ends of the earth unless we help save the people in the very situations in which we live.” These situations, these people where we live, have been entrusted to us. When we don’t take this mission seriously, the world suffers.

Her words profoundly challenge me. I am often dreaming of my next “important project,” but fail to see the people and the situations that are very truly before my eyes.

The Spiritual Life—A Three-fold Cord is not Quickly Broken: Fasting in the Christian Life

Every Ash Wednesday around the globe—in lavishly tiled basilicas, in wood planked chapels, in modest oratories with dirt floors, and in carpeted and cushioned suburban parishes—Catholics are called by Christ himself to reflect on the three great activities of Christian discipleship:

“When you pray…”

“When you give alms…”

“When you fast…”

For nearly two thousand years, Catholics have read, re-read, and reflected upon these three passages from the sixth chapter of Matthew. When the Ash Wednesday Mass concludes, the following forty days—all of Lent—is observed within this context.

How many Catholics understand that a normal living of the Christian life is to be composed of a healthy dose of all three? Sure, we’re supposed to pray. Everyone believes that. Giving alms (once we get past the archaic word) is also commonly accepted. In the United States and many other countries, giving to charities and doing service work is considered a normal part of our civic life. Nothing too unusual here.

But fasting? Who fasts? And if we do fast, isn’t it just obedience to some minimal Church norms during Lent? But where does Christ or the Church say that fasting is to be done exclusively during penitential seasons such as Lent? Where does Christ say that it should be so rare and so minimal? And where does he say that it is to be exclusively penitential? Nowhere. Yet for some reason these things are precisely what most of us think. Let’s take another look at what he and his disciples actually said and did when it comes to fasting.

When Jesus was preparing for his public ministry, where did he go and what did he do? He went out into the desert and spent forty days praying and fasting. Was Jesus doing penance? Of course not. He never sinned. He was preparing himself spiritually, seeking closeness to his Father in heaven. So, while doing penance is a very good reason for fasting, Jesus gives us other good reasons to fast.

How important was his fasting in this time of preparation? Consider Matthew 4:1-4: when the devil appeared to Jesus to try to thwart his mission, the very first thing he tried to do was to get Jesus to break his fast! Yes, fasting is that powerful and the devil understood this profoundly.

Later in his ministry, when Jesus’ disciples discovered that certain demons could resist their prayers of deliverance, Jesus informed them that some demons can only be cast out by prayer and fasting (cf. Mt 17:21). Obviously there is a power in fasting that goes beyond prayer alone.

To pray is good. To give alms is good. But fasting is the glue. In striving for holiness, prayer lifts us up. Almsgiving coupled with prayer is a selfless movement of love that powers us higher; but fasting allows us to soar to supernatural heights otherwise unimaginable! This is not because we ourselves are in control, but because fasting is an abandonment of control. It is a radical letting go that, coupled with sacramental confession, allows all barriers to our acceptance of God’s love to be broken.

Pursuing Holiness in the Single Life

Maybe it’s too much of a stretch to say that an unmarried tailor who lived with his mother is the reason communism fell in the west. Then again, maybe it’s not.

Venerable Jan Tyranowski was, in many respects, an ordinary working class bachelor. But when he was 35, a homily changed his life. “It is not difficult to become a saint,” the priest said, and Tyranowski believed him. He began reading the Carmelite mystics and praying up to four hours a day. When many of Poland’s priests were sent to death camps in 1940, one of those left behind asked Tyranowski to become more involved in youth ministry.

That’s where he met Karol Woytyla. The young man who would become pope was just a 20-year-old in youth group, but his relationship with Tyranowski changed everything. Karol had become unsure about the wisdom of putting so much emphasis on the Blessed Mother, but Tyranowski pointed him to St. Louis de Montfort, thus shaping the life and papacy of the man who would be the most Marian Pope since St. Peter. Perhaps more importantly, Tyranowski’s work with the young Woytyla (especially after Karol lost his father in 1941) greatly influenced Wotyla’s vocational discernment. A friend of St. John Paul’s from that same youth group insists that John Paul owed his priestly vocation to the single tailor.

Tyranowski died only a few months after Fr. Woytyla was ordained. He didn’t live to see his young friend consecrated bishop or elected pope. He didn’t see the work of the Polish pope break the stranglehold of communism on Poland and her neighbors. Through it all, though, St. John Paul kept a picture of his youth minister on his desk, a single man whose life changed the world.

Inspired Through Art: The Virgin of the Rocks

This mysterious painting by Leonardo depicts a non-biblical meeting between Our Lady, the Christ Child, and an angel with St. John the Baptist in a rocky grotto. It is the second version of a painting originally commissioned in 1483 to be the central panel of a large altarpiece for the Franciscan Confraternity of the Immaculate Conception in Milan, Italy. While the subject of the Madonna and Child with an infant St. John the Baptist was celebrated throughout the Renaissance, the presence of St. John in this particular setting makes the inspiration for the painting difficult to assess. Though the infant St. John is not recorded as being present in Scripture, Leonardo’s version could possibly be following a medieval tradition of portraying the Holy Family during their flight into Egypt, hence the rock-strewn landscape. While the exact source of the narrative is uncertain, the painting’s rich iconography and harmonious design contain a wealth of meaning. In addition, the unique method of observation Leonardo has employed to the scene sets the painting apart from other artists’ interpretations of the theme.

An Extraordinary Scene

Our Lord is sitting on the ground supported by an angel. The position of Mary’s hand above the Infant’s head as well as her drooping cloak, which stops just short of his extended right hand, produce a vertical movement within the composition that stresses the Christ Child’s importance. Both Christ and the angel look in the direction of St. John; a silent dialogue we are blessed to witness. The environment around them serves to reinforce their otherworldliness. Clark adds, “Like deep notes in the accompaniment of a serious theme the rocks of the background sustain the composition, and give it the resonance of a cathedral.”[9] The fantastical nature of this “cathedral” of caverns points to the profound mystery of the beings in this drama. It is not strange for its own sake; rather it heightens our awareness of the supernatural. The rocks themselves are standard symbols of Christ. Revisiting Ferguson, this attribute “is derived from the story of Moses, who smote the rock from which a spring burst forth to refresh his people. Christ is often referred to as a rock from which flow the pure rivers of the gospel.”[10] The cool body of water in the background recedes into a far-off misty mountain scene not unlike a landscape one would find in J.R.R. Tolkien’s Middle Earth. Leonardo’s imagination seemed to know no bounds.

It was an imagination informed by his relentless investigation of the natural world. To heighten the aforementioned three-dimensionality of the painting, Leonardo incorporates his perceptive studies of light, shade, and perspective. These studies can be read in the publication of his numerous notebooks. He writes, “Painting is concerned with all the ten attributes of sight: darkness and light, solidity and color, form and position, distance and nearness, motion and rest.”[11] This painting contains all of these elements. When the results of Leonardo’s explorations into sight and of the natural world are united with religious subject matter, the effect is a true masterpiece of sacred art.

Editor's Reflections: Barbara Morgan—Pursuing Holiness

What is holiness? In our lead article, Dr. John Cavadini describes holiness as the Second Vatican Council did, as “the perfection of love.”[1]

What is holiness? In our lead article, Dr. John Cavadini describes holiness as the Second Vatican Council did, as “the perfection of love.”[1]

AD: Discovering Mary, the Church, & the Papacy books by Ignatius Press

This is a paid advertisement in the April-June 2019 issue. Advertisements should not be viewed as endorsements from the publisher.

The Spiritual Life: Madeleine Delbrêl, French Mystic and Evangelizer

“We, the ordinary people of the streets, believe with all our might that this street, this world, where God has placed us, is our place of holiness.”

“We, the ordinary people of the streets, believe with all our might that this street, this world, where God has placed us, is our place of holiness.”