Engaging the Domestic Church in Children’s Catechesis

The family has a privileged place in catechesis. The Catechism states that “parents receive the responsibility of evangelizing their children” and calls them the “first heralds” of the faith (2225). The family is called “domestic church”—the church of the home (CCC 2224). For this reason, parents are the first and most important teachers of the faith for their children. In recent decades, however, it has been difficult for parishes and Catholic schools to make the shift to practices that are consistent with this understanding. Parents have come to think of the parish and school as the places where children are taught about the faith, and many families have left it almost entirely to these institutions to catechize their children. Still, recently, the quarantine that resulted from the COVID-19 pandemic thrust us into a new reality—one in which, by necessity, children were learning everything, including their faith, at home. How might we use the momentum and opportunities that have been gained in this moment to craft an approach to catechesis that engages the domestic church in new ways? Here are a few suggestions for partnering with parents.

Give families ways to connect faith to everyday moments of family life.

When we hear that parents are the first and most important catechists of their children, we are sometimes tempted to encourage a didactic-style catechetical session in the home. While it’s wonderful for parents to conduct full lessons with their children, especially lessons about their faith, there are a variety of reasons—including time, confidence, and competency—that might make parents hesitant to dive into a full-length catechetical session at home. Sure, parents are primary catechists, but the parish is also a privileged locus of catechesis. The parish helps to make catechesis systematic and comprehensive, equipping parents in their role of bringing the faith to life through everyday experiences.

If, rather than trying to turn every home into a traditional classroom, we give parents the tools to connect faith to life in ordinary moments, we can assist families in developing a truly Catholic identity and worldview. Rather than offering a worksheet the family completes together, consider offering one way to live the content presented that week or reflect on its connection to our daily lives at home. For example, if a second grader has just completed a lesson that includes the Gospel in which Jesus says that he is the Bread of Life, offer parents this instruction: “This week, when you serve your children bread (e.g., a sandwich or a roll with dinner), remind them that Jesus said he is the Bread of Life. Ask them, ‘What did Jesus mean when he said this?’”

Catholic Education: Directing Students to God

Recently, I spoke with a graduate student in one of my courses on Catholic schools. Because she is not a religion teacher, she struggled to understand how she could carry out the mission of Catholic education. This faith-filled woman knew she was serving the Lord by fulfilling her duties conscientiously, but she did not recognize how her work could foster her students’ spiritual lives. She needed a vision for carrying out her educational activities in a way that leads her students to God. I illustrated for her how she could teach her subject area so that her students learned from it more about who God is and how He wants us to live. By teaching this way, I told her, they could not only prepare for the next grade level or their future job but they could also live in greater union with God and in preparation for Heaven. Her teaching, I explained, had the potential to impact students eternally. When she heard this she exclaimed, “You make me sound important!” We ended our call with her excited to tackle her upcoming tasks with this entirely new focus.

Unfortunately, this woman is not unique or even unusual among Catholic educators. Typically formed by secular educational programs that do not address the spiritual dimension of education, Catholic educators find themselves at a loss as to how they are to help students cultivate their relationship with God or recognize the eternal purpose to their studies. When teachers understand how to carry out their teaching duties with a “supernatural vision,” they experience excitement about enriching their students’ lives beyond just the next 70-odd years.[1] They begin to sense their value and importance to the Catholic educational endeavor. The result is a more effective mission implementation that bears fruit in time and eternity.

The Goal of a Catholic Education

Above all else, a Catholic education directs students to God. A Catholic education resembles a civic education by providing an integral formation for students, addressing not just the intellectual, but also the social, emotional, and (to some extent) physical growth of its students.[2] But unlike secular education, every Catholic educational effort should begin and end in Christ, with Gospel principles serving as educational norms.[3] This orientation directs students to their ultimate goal: eternal communion with God. In short, a Catholic education should help students get to heaven. It forms the student spiritually, teaching them to know God ever better, to have and develop a relationship with him, to recognize him in everything, to live so as to become closer to him and more like him—all so that they can spend eternity in a loving, blissful union with him.

A Catholic school can explicitly orient to God the myriad of activities that make up “school.” For this reason, it can be said that all teachers in Catholic schools are catechists. It can feel daunting to teachers who do not teach religion to hear that they are expected to be catechists because they believe they are expected to answer doctrinal questions that are beyond their capability. Certainly the better the teacher can accurately respond to doctrinal questions the greater the benefit to the students. But a teacher does not need a degree in theology to carry out teaching responsibilities with the intention that those activities form students to live as disciples of Jesus. The very activities that constitute the nature of a school, when imbued with a focus on the student’s eternal destiny, form and prepare the student for that destiny.

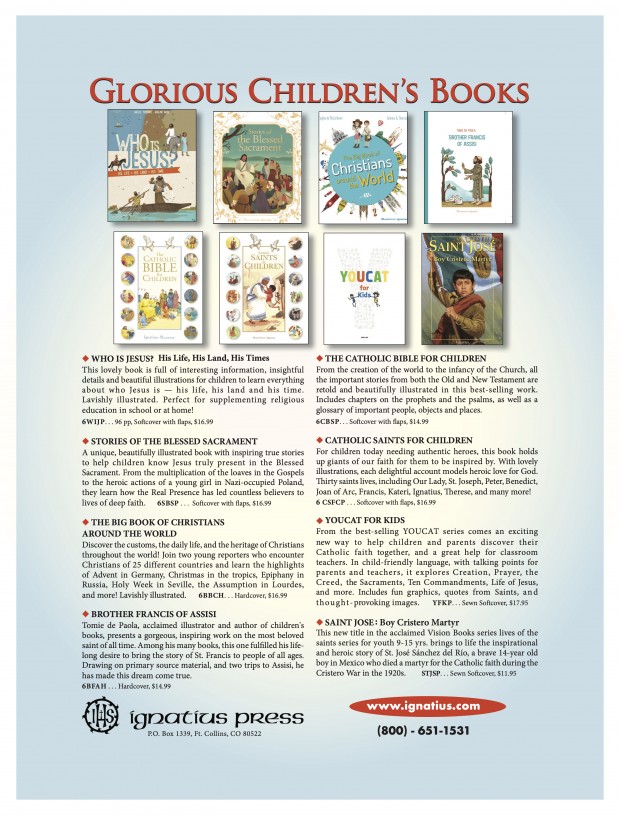

AD: Catholic Children's Books by Ignatius Press

To order these children's books call 800-651-1531 or visit www.ignatius.com.

This is a paid advertisement and should not be viewed as an endorsement by the publisher.

Encountering God in Catechesis

#1–Trusting God to Take the Lead

A couple years ago, I volunteered as a first-grade catechist for my parish’s religious education program. This was before I was taking any classes or working in ministry, and I often struggled with how to present material to such a young age. The program we followed wasn’t much help; the kids I taught did not seem to connect to the content at all. I modified what I could and tried to make it fun, but often I felt my efforts were inadequate.

One Sunday morning, I was teaching on the parable of the workers in the vineyard from Matthew 20:1-16. I read the parable to the students, but I got no reaction. Many students were clearly distracted. Those who were at least looking at me had blank looks on their faces. I was at a complete loss. I knew I needed to do something to get the message across, but I had no idea what to do next. I turned to God. I said a quick prayer asking for help and went with the first idea that came to mind... (testimony by Emily Ketzner)

#2–My Conversion, His Conversion

When I returned to Trinidad during the summer of 2018 for a short-term mission, I attended Mass at one of my favorite churches in Paramin called Our Lady of Guadalupe. I heard somebody calling my name from behind me, so I turned around and saw my friend and former student Chris. I was so happy to see him and looked forward to talking with him afterwards. During Mass I thanked the Holy Spirit for the work he had done in Chris’ life. We had a long talk after Mass; I was in awe seeing him still open to growing in faith and being active in the Church after so many years, despite the rough journey he shared with me.

Chris was one of the youths that I journeyed with years earlier. He was part of the Confirmation class and Youth Ministry group. I met him during our youth retreat, and he was one of those boys who would always get your attention by talking and not paying attention. I remember my patience was tested... (testimony by Jonathan Lumamba)

Children's Catechesis: Fostering Imagination in Children

A few months past, I had the rare privilege of observing our three youngest grandchildren at play in a Houston park burying treasure (rocks) and marking the spot with a flag made of a stick and a carefully curated large leaf. Their lively play, contagious joy, and the delightful way they encouraged one another in their imaginative play made for one of those transcendent experiences we wish would never end. These moments drew me to think more deeply about what I was witnessing. What was it that made their play so compelling? The components were simple and rooted in ordinary elements. The sand, rocks, leaves, digging, and planting served as fodder for their free imagination. The children were completely unrushed and at peace yet actively engaged. How can we offer our children unhurried time immersed in reality so their imaginations can flourish?

I began with looking at what the Catechism of the Catholic Church has to say about the imagination. In one of only two references, I discovered the Catechism links our cognitive and volitional faculties with imagination. “Meditation engages thought, imagination, emotion and desire. The mobilization of faculties is necessary in order to deepen our convictions of faith, prompt the conversion of our heart and strengthen our will to follow Christ” (CCC 2708).

La primera catequesis sobre virtudes

Aun cuando los documentos del Magisterio sobre la catequesis se refieren a los padres como los educadores primarios en religión, muchos padres y educadores religiosos en nuestras parroquias, no comprenden la importancia de esta afirmación. No se espera de los padres que hagan una catequesis formal, de tipo escolar. En cambio, el rol de los padres es uno que solamente ellos están llamados a cumplir: su responsabilidad vocacional para inculcar la Fe en un plano cotidiano, a través de la oración, la celebración litúrgica y la formación moral. A diferencia de los catequistas, que suelen tener solamente una hora por semana con los niños, los padres están con sus hijos diariamente a través de sus años formativos, con el potencial de establecer en ellos hábitos de oración, alentar la participación en la liturgia, y dirigir un progreso real en su formación moral. Mientras que los catequistas en la parroquia y en la escuela bien puedan proporcionar dirección y consejos, además de enseñar la doctrina, sin embargo, los padres y los miembros del núcleo familiar son esenciales para una correcta vivencia de la Fe. Una buena formación en el seno familiar, por lo tanto, provee un buen fundamento para la catequesis formal, de modo que los dos pueden ser enriquecidos mutuamente.[1]

Los padres son indispensables en el desarrollo de la consciencia y de la virtud. Esto se debe a que, como el Directorio Nacional para la Catequesis, explica: “La catequesis en cuestiones morales involucra mucho más que la proclamación y la presentación de los principios y la práctica de la moral cristiana. Presenta la integración de los principios de la moral cristiana en la experiencia de vida para el individuo y la comunidad.” [2] La familia es para el niño la primera y más importante comunidad para este aspecto esencial en su formación moral. El Directorio Nacional para la Catequesis confirma que los padres son responsables de la formación moral de los niños, de acuerdo a la ley natural. “Los padres son catequistas, precisamente porque son padres. Su rol en la formación en los valores cristianos en sus hijos es irremplazable.”[3]

¿Qué es la virtud? ¿Qué es el bien?[4]

La virtud es un hábito o habitus. La forma latinizada se debe preferir aquí, porque nuestro entendimiento familiar de la palabra “hábito”, no está en consonancia cuando consideramos la virtud. Como habitus, la virtud ocupa una posición entre las potencias del alma y los actos de una persona. No es simplemente una acción repetida; es una habilidad dinámica de crecimiento hacia el bien en una acción humana. Se requiere de un habitus para hacer funcionar las potencias humanas que tienen más de una manera de ser activadas. Mientras que cada sentido físico, por ejemplo, tiene una particular función: los ojos ven, los oídos oyen y la lengua gusta, la voluntad, por el contrario, puede desear muchas cosas, requiriendo para ello un habitus para darle forma; una voluntad recta, una voluntad débil, malicia, todos describen el habitus de una voluntad particular. El habitus, en sí mismo, es un término neutral, que se refiere simplemente a un patrón de crecimiento en una potencia humana en particular, dirigido hacia determinados tipos de acción. Por ejemplo, una persona de buena voluntad tiene un patrón de crecimiento en la virtud, pero la persona maliciosa tiene un patrón de crecimiento hacia el vicio. Las virtudes se desarrollan a través de una acción humana correcta, y el trabajo en conjunto del intelecto y de la libertad, que afecta no sólo a las acciones ejecutadas, sino también resulta en el desarrollo moral de una persona humana. La virtud de la valentía ayuda a perfeccionar los movimientos del apetito irascible del alma en acciones que toman cuerpo en buscar el bien en circunstancias adversas. Las capacidades verdaderamente humanas del conocer y del amor requieren de la virtud para funcionar bien. Además, el carácter moral de una persona cambia a través de la virtud, de modo que la persona con virtud es una buena persona.

El bien es un concepto análogo. Cada cosa posee o muestra el bien de un modo que es específico al tipo de cosa que ella es. Un bolígrafo bueno escribe bien, una silla buena está construida de tal manera que soporta a la persona que está sentada sobre ella. Para que una persona sea buena, las potencias del alma, las emociones, y las pasiones deben estar guiadas por el intelecto hacia el propósito o el objetivo en la vida. Los padres cristianos están guiando a sus hijos a los más grandes objetivos: la unión con Dios, a través de la imitación de Cristo. Este es el bien que surge a través de la virtud. [5] El crecimiento en la virtud, por tanto, significa crecimiento en el bien, una acción buena consistente que trae alegría al agente.

Children's Catechesis: Contemplation for Each of Us

Can a businessperson aspire to contemplation? A parent? A teenager? A young child? Don’t we usually see it as a privilege reserved for monks and cloistered nuns? Father Marie Eugene of the Child Jesus would say that each of us is capable of genuine contact with God, including the young child.

Blessed Marie-Eugene was a French Carmelite priest born in 1894. He discovered in Carmel the treasure of intimacy with God—not only through a daily two hours of silent prayer but throughout the day—thanks to St. Teresa of Avila, St. John of the Cross, St. Therese of the Child, and Jesus's experiences and teaching. God is always ready to pour out his goodness, his lLove. Marie-Eugene's dream was to help everyone realize that this treasure is within reach. Anyone can live close to God, as God's close friend. Everyone is called to live an intimate friendship with God!

Led by his “best friend” the Holy Spirit, and by the Virgin Mary in whom he trusted completely, this wholehearted priest founded the Notre Dame de Vie (Our Lady of Life) Institute, where priests and lay men and women are called to live this intimacy with God in an unconditional consecration, being active through contemplation and contemplative through action, whatever their jobs may be. Today, there are five hundred members all over the world.

In the Notre Dame de Vie schools, children can discover this treasure of contemplation as well. Silent prayer is made available to them in theour schools in order that they might live with God the whole day long.

AD: Newest Title in YOUCAT Family: YOUCAT for Kids!

This is a paid advertisement in the January-March 2020 issue. Advertisements should not be viewed as endorsements from the publisher.

Children's Catechesis: Students, Families, and Evangelization in the Catholic School

Evangelization is a primary function of Catholic schools. Although they provide quality education in a variety of subject areas, as agents of the Church, they share the larger mission of the Church: forming disciples of Jesus Christ. Catholic schools should and must be more than public schools that also happen to have religion classes. Speaking about the role of the Catholic school, the Vatican II Declaration on Christian Education, Gravissimum Educationis states, “But its proper function is to create for the school community a special atmosphere animated by the Gospel spirit of freedom and charity, to help youth grow according to the new creatures they were made through baptism as they develop their own personalities, and finally to order the whole of human culture to the news of salvation so that the knowledge the students gradually acquire of the world, life and man is illumined by faith” (8). A key role of the Catholic school, then, is as an agent of evangelization.

Schools can live out their mission to evangelize in a number of practical ways, including evangelizing students, evangelizing the family, and preparing students and families to evangelize the community.

Catholic Schools Evangelize the Student

Providing religious education is a key priority in the Catholic school, but religious education must be different than education in mathematics, science, history, or other subjects. If our objective is to form disciples, the Catholic Faith cannot be simply approached intellectually. Religious education in the Catholic school must be an immersive and formative experience that begins with an encounter with Jesus Christ through the proclamation of the kerygma.

Knowing Jesus is different from simply “knowing about” him. As we draw closer to Jesus, our lives are changed—we find the joy of becoming who we were made to be, we are challenged, and we are called to places we might have never gone before. A Christocentric catechesis—one that focuses on the person of Jesus Christ—facilitates an environment in which learners can get to know Jesus and draw closer to him.

Help learners become acquainted with the Gospels, particularly the Paschal Mystery: Jesus’ death, resurrection, and ascension. Periodically choose a passage from the Gospels that is developmentally appropriate for your learners, both in length and content. Invite your learners to relax, close their eyes, and imagine themselves somewhere within the Gospel story. After meditating on the Gospel passage, invite learners to reflect on their experience. What did they hear Jesus saying to them, and how does it connect with their lives today?

Evangelizing the Catholic School

What makes a school Catholic? Is a school Catholic because it exists with the permission of the bishop of the diocese, or it is a member of the National Catholic Educational Association (NCEA), or it is an extension or an outreach of a parish community, or it has a crucifix in every classroom and religious artwork throughout the building, or because its curriculum includes religious studies, or because the pattern of its practices align with the National Standards and Benchmarks of Effective Catholic Schools, or because Mass and the Sacrament of Reconciliation are celebrated for the student body during the school year?

For sure, each of these elements is a marker of a Catholic School. But I dare to say that the most decisive element of a Catholic school is the religious character of its personnel.

When the administrator(s) and a critical mass of faculty members embrace Jesus as their center (rather than mention him as an afterthought or an add-on), his spirit infuses the campus. It becomes evident to all that it is the primary purpose, consistent attitude, and intentional goal of the school to guide students to know, love, and serve God. When a Jesus-centered mindset drives every endeavor, action, decision, and response, self-disciplined students, who seek to develop their personal best, emerge. These hallmarks of a Catholic school (a Christ-centered environment, self-disciplined students, and academic achievement) are rooted in the religious character of its teachers.

“Back in the day” Catholic schools were predominately staffed by men or women religious whose distinctive garb was, itself, an outward reminder of God. It seemed as though these walking icons were everywhere, had eyes in the back of their veil-covered heads, and appeared where you least expected them! While students labored over final examinations, they observed their teachers fingering rosary beads suspended from their waists. At precisely the opportune moment, Scripture quotes seemed to slip from their lips effortlessly. Oftentimes, students could observe their teacher clutching the large crucifix that hung from the neck. Teacher body-posture, classroom decorations, routines, consistency in procedures, and high expectations set a tone. The school day was hemmed in with prayer or sacred ritual. At morning prayer students consecrated the day to God, and at dismissal they examined their consciences and made an act of contrition.

An intentional awareness of God punctuated the entire school day. For instance, long before marketers raised awareness of “WWJD?” via bracelets, posters, and such, these teachers motivated student decision-making by remarking, “What would Jesus do …or say…or desire?” “How will this choice contribute to the greater glory of God and the salvation of your soul?” “Live Jesus!” On every heading of student papers and copybook pages students drew a cross followed by “JMJ,” “JMJAT,” “AMDG” or an acronym-inscription related to the charism of the religious congregation. In my elementary school, every hour on the hour, a designated student rang a bell and intoned: “Pardon me, Sister. Pardon me, Class. It is time to bless the hour.” All activity ceased. The student then said, “Let us remember that we are in the holy presence of God.” The class responded: “Let us adore God’s divine majesty.” Together we prayed the “Glory be” and promptly the lesson continued wherever it had been interrupted. Wherever students happened to be at 12 noon, inside or outside the building, they stood still and prayed the Angelus formula while the Angelus bells rang in the distance. When emergency sirens were heard, the class prayed an aspiration or formula that asked God’s assistance for the unknown person in need. When Church bells tolled for a funeral, class stopped for a moment of silence and/or to pray for the deceased, “Eternal rest grant unto him, O Lord, and let perpetual light shine upon him. May his soul and all the souls of the faithful departed through the mercy of God rest in peace. Amen.”

Additionally, religious instruction occurred daily, usually as the first session of the day. And, in many schools, the afternoon session began with a 15 minute period of story-telling that applied faith to action. Nothing else trumped Religion class! Some textbooks even referenced Catholic culture. Then, too, there were rituals of the liturgical seasons (Advent, Christmas, Lent, Easter, Pentecost), devotions to Mary (rosary, May Procession), Eucharistic devotion (frequent Mass, Forty Hours’ visits to the Blessed Sacrament, Benediction), Stations of the Cross, litanies and novenas, and regular participation in the Sacrament of Penance. The combination of all of these kinds of customs created a culture, an ambiance, a Godly reverence that pervaded every aspect of schooling. This culture underscored the sense that the institution was a divine enterprise and its teachers were the custodians of its spiritual nature and essential to its effectiveness.

The Catholic school was essentially an extension of convent or priory life. School practices, priorities, and order mirrored the lifestyle of the vowed religious. By 1970, the numbers of men and women religious in the schools declined tremendously. If their shoes were filled by lay counterparts, who had themselves been educated in the kind of Catholic school just described, the Catholic Identity or Catholic Culture continued in a similar fashion or adapted modern expressions that created the same end: a faith-infused environment; a divine, God-centered enterprise where activities reflected the spirituality of the teachers.

Over time, elements like a competitive market, certification requirements, and national standards impacted school design. Program demands increased; the length of the school day/year did not! Faith-related cultural customs were deleted. Simultaneously post-Vatican II faculty members—though faithful and faith-filled, well-educated, practicing Catholics—had no experience of schooling within “the Catholic bubble” and that style of spirituality was foreign to them. Consequently, maintaining or fostering Catholic identity or Catholic culture relied all the more on the religious character of school personnel.