Formación religiosa incluyente para niños: Tres partes, una comunidad

En el año 2005, la Conferencia de Obispos Católicos de los Estados Unidos publicó el documento titulado, The National Directory for Catechesis [El directorio nacional para la catequesis], lo cual declara, “toda persona con discapacidad tiene necesidades catequéticas que la comunidad cristiana tiene el deber de reconocer y satisfacer. Toda persona bautizada con discapacidad tiene el derecho a una catequesis adecuada y merece los medios para desarrollar su relación con Dios.” [1] Mi interés y participación en la formación religiosa de niños con discapacidades tiene sus raíces en mi experiencia personal. Al buscar respuestas acerca de lo que mejor nos convenía como familia, descubrí que nuestra historia era común; y aunque algunos estudiantes reciban una catequesis en su hogar, los estudiantes que se ausentan de los programas parroquiales para la formación de la fe se pierden de un elemento fundamental de la fe cristiana: la comunidad.

¿Dónde están los niños con discapacidades?

Como la mayoría de los padres de familia, nunca me imaginaba que mi hija iba a necesitar una educación especial. Mi esposo y yo teníamos el sueño y el objetivo de educar a nuestros hijos en una escuela católica desde el jardín de niños hasta el final de la educación media superior o grado 12. Cuando nuestro quinto hijo, Grace, entró al kínder, aquel sueño comenzó a desmoronarse. Sabía, desde el primer día, que Grace iba a necesitar de una ayuda adicional para mantenerse sentada, hacer filas y esperar su turno. De lo que aún no me daba cuenta era que su falta de contacto visual, su incapacidad para recordar los nombres de los miembros de la familia extendida y su obsesión con los dinosaurios eran indicadores de un trastorno del Espectro Autista, un diagnóstico que no recibimos sino hasta el verano posterior a su año en jardín de niños. Las lagunas de Gracie en cuanto a sus habilidades comunicativas fueron percibidas como una falta de respeto, su falta de habilidades sociales como una falta de amabilidad para con sus compañeros de clase, y sus sensibilidades sensoriales como un comportamiento inmaduro, incluso salvaje. Mi esposo y yo tomamos entonces la decisión de soltar nuestro sueño, y Gracie pasó a formar parte del 13 por ciento de niños que reciben servicios de educación especial en la escuela pública. [2] Sabíamos que teníamos que proporcionarle a nuestra hija su formación en la fe; elegimos enseñarle en casa desde el principio. Durante tres años nosotros mismos le enseñamos a Gracie y le preparamos para su Primera Reconciliación y su Primera Comunión utilizando los materiales para la educación en la fe de nuestra parroquia.

La mayoría de los niños que asisten a los programas católicos de formación en la fe provienen de escuelas públicas. Si el 13% de los niños que asisten a la escuela pública reciben educación especial, es de esperar que el 13% (uno de cada ocho) de los alumnos que asisten a programas de educación en la fe requieren de algún tipo de apoyo educativo para optimizar sus resultados de aprendizaje. San Juan Pablo II definió el resultado de aprendizaje óptimo para la educación religiosa: “el fin definitivo de la catequesis es poner a uno no sólo en contacto sino en comunión, en intimidad con Jesucristo…”.[3] En la tradición católica, esto también abarca la preparación y la recepción de los Sacramentos de la Reconciliación, la Eucaristía y la Confirmación.

El número de estudiantes con discapacidades que asisten a programas de formación en la fe no corresponde a las estadísticas. Es posible que los padres de familia no revelan toda la información acerca de las necesidades de sus hijos o simplemente no les inscriben. Las razones varían. Los padres de niños con discapacidades a menudo tienen muchas obligaciones adicionales relacionadas con el cuidado de sus hijos. Hay citas con el doctor, citas con terapeutas y juntas adicionales cada ciclo escolar con los maestros y el personal de apoyo en la escuela de sus hijos. Algunos papás pueden encontrarse justo en el límite de lo que puedan manejar. Algunas familias pueden haber experimentado el rechazo de su comunidad de fe y creen que el programa parroquial de formación en la fe no podrá o no querrá acomodar las necesidades de sus hijos. [4] Los niños con discapacidades deben de ser incluidos en todos los programas católicos para la formación en la fe. Para lograr su incorporación, es cuestión de crear comunidades cristianas incluyentes que den la bienvenida a los niños con discapacidades y a sus familias.

More than in the Movies: Introducing Consecrated Religious Life to a New Generation

“Mom, what’s that?” a little girl in the grocery store unabashedly asked as I walked past them in the produce aisle. Slightly embarrassed at her daughter’s rather loud and candid question, her mother simply and timidly responded “She’s a lady who loves Jesus.” I smiled at both mother and daughter and gave a little wave as I kept on in pursuit of the items on my list. In living my call to consecrated religious life over the past thirteen years, there have been plenty of experiences similar to this and I am sure that every sister has a supply of her own. Humorous as they may be, still they point to a sad reality that consecrated religious life is not as visible or fostered as it was in decades past and that the simplistic answer may have been the extent of that mother’s knowledge of the reality of this state in life. There was a time when most young people were exposed to sisters in the classroom, parish, or even in the family, but those days are gone. Most knowledge of religious life comes rather from movies like “The Sound of Music” or “Sister Act,” but the life of consecration has a depth and beauty worth studying and sharing with a generation that tends to long for more and settle for less. Throughout Salvation History, God has called men and women to follow him in the consecrated life. They have borne witness to the Gospel by living heaven on earth. In this way, they have revealed the providence of God in every age through their trust and their loving service to their brothers and sisters in need. From the earliest days, God called individuals to himself, as with the desert fathers, but that expression of single-hearted following of Christ eventually flowered into individuals living a dedicated life in community. Founders and foundresses responded to the needs of each particular time and established religious institutes within which members consecrated themselves to God through vowing the Evangelical Counsels, living in community, and serving according to their particular situation in apostolates such as health care, education, and care for the poor and needy of every condition. God’s call goes forth even today inviting young people to forsake the promises of the world for the sake of embracing his eternal promises. Vowing to live poverty, chastity, and obedience in a world that exalts material goods, sexual license, and individualism is counter-cultural to say the least, but it is a path worth discerning and a journey worth taking. Catechists have a particular role to play in assisting young people to encounter the truth and beauty of a call to be consecrated to God through the profession of the evangelical counsels through education and exposure. While the General Directory for Catechesis instructs that “every means should be used to encourage vocations to the priesthood, and to the different forms of consecration to God in religious and apostolic life and to awaken special missionary vocations,”[1] it is essential to remember that God is the source of every vocation. The role of the catechist is to propose to students that such a particular vocation is not just in the movies and that there is a real possibility that they could be called and ought to learn to listen to the gentle voice of the Good Shepherd.

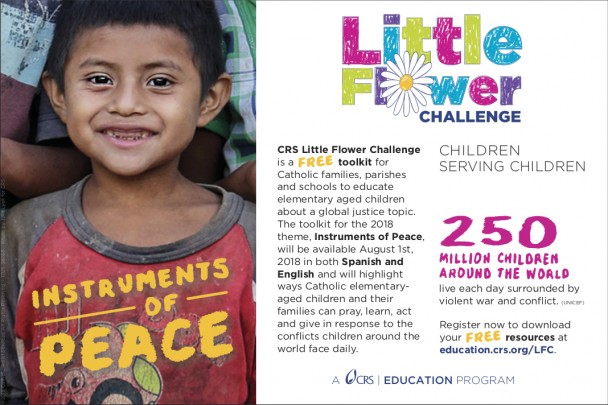

AD: Catholic Relief Services Little Flower Challenge Tool Kit for Families & Schools

Register now to download your resources at education.crs.org/LFC.

Youth & Young Adult Ministry: Screen to Soul—The Challenge of Catechesis in the Digital Age

There is probably a screen in the middle of your living room. There has been a screen in the middle of American living rooms since the 1950s. Its presence rearranged furniture and changed the focus of the ones sitting in those chairs—no longer looking at one another, but pointed at that screen.

There is probably a screen in the middle of your parish youth room or classroom, too. Maybe it is a large white screen built into the wall with a 4K projector, or an old console TV precariously perched atop a moving cart. It wasn’t always at the center, but over the past five-to-seven years it crept into the middle and redirected the focus as video-based catechesis has presented itself (perhaps unintentionally) as the solution to many challenges we face in ministry.

Mystagogy and the Empty Tomb

The sea change in the approach that American teens and young adults take in regard to Christian faith just in the last decade has been rapid, palpable, and sometimes stunning. We live in a time in which “nearly half of cradle Catholics who become ‘unaffiliated’ are gone by age eighteen. Nearly 80 percent are gone and 71 percent have already taken on an ‘unaffiliated’ identity by their early twenties.”

According to Jean Twenge, a professor of Psychology at San Diego State University, the experience of faith has been complicated even further by the staggering increase in social media usage among these same teens and young adults, which has been accompanied by a correlative increase in feelings of depression, joylessness, and uselessness—as well a significant increase in suicide attempts. One of the most notable attributes of this generation, which Twenge calls “the iGen generation,” is its marked aversion to practicing, or even identifying with, Christianity.

We have seen many of these same trends in the high school in which I have taught theology and operated as campus minister during the last twelve years, but our overwhelming experience is that underlying most teenagers’ sense of disconnect from Christ and/or their Catholic faith is a sense of pain and confusion caused by suffering in their lives. Even when they do not share these things openly, we know that our students have suffered through broken homes, health problems, various kinds of anxiety and depressive disorders, romantic breakups, betrayal from friends, drug and alcohol abuse, self-harm, and every other imaginable problem. Knowing that the students don’t always have the desire or, in some cases, the ability to share these things, we make it a priority to find a way for them to share it with the Lord.

Christopher Dawson’s Vision of Culture and Catechesis

What is the goal of catechesis? To make the faith the center of our lives. St. John Paul II made this clear: “Catechesis aims therefore at developing understanding of the mystery of Christ in the light of God's word, so that the whole of a person's humanity is impregnated by that word.” We come to know Christ so that he can shape the way that we live concretely and as a whole. Pope Benedict XVI said the same about Catholic education more broadly, claiming that it should “seek to foster that unity between faith, culture and life which is the fundamental goal of Christian education.” An important reason why catechists have to work for this goal is that education is the way in which we pass on an identity and way of life. Education forms culture, understood broadly as our way of life. Our children will either use their faith to navigate the challenges of the world or will subordinate their faith to a secular worldview. Catechists impart not just the content of the faith but seek to form a life that embodies that faith. If our children conform to the secular culture more than to the faith, this entails a breakdown of our catechetical and educational efforts. Christopher Dawson, more than any other Catholic thinker, has recognized the centrality of religion in culture and education’s role in forming culture. Dawson (1889-1970) was an English-Welsh convert to Catholicism and an historian who produced a vast synthesis of history, the human sciences, and theology stretching from prehistoric times to the crisis of the mid-twentieth century. The thread that united all of his works was the thesis that religion is the heart of culture. Tracing the role of religion throughout history, he noted that modern culture has a void in place of this heart, which it attempts to fill with other secular ideologies. Without a religious renewal, Dawson thought the material advances of technology would prove self-destructive for our culture, a prediction which partially came true in the World Wars.

Youth & Young Adult Ministry: Redefining "Youth" in the United States

It is a historic time to be a part of youth and young adult ministry. The upcoming Synod on “Young People, the Faith, and Vocational Discernment” is inspiring conversations across the world. Here in the United States, the Hispanic/Latino community has engaged in the Fifth Encuentro with an emphasis on young, second and third generation Hispanics/Latinos. Another important movement is “The National Dialogue of Catholic Pastoral Ministry for Youth and Young Adults”, which is a collaborative effort between the USCCB, The National Federation for Catholic Youth Ministry, the USCCB National Advisory Team on Young Adult Ministry, and the National Catholic Network de Pastoral Juvenil Hispana (LaRED).

It is well documented that many young people no longer affiliate themselves with being Catholic, or any religion at all. Before we can propose what can be done about this, some attention must be given to who these young people are. To do so challenges not only our pre-conceived notions but also the vocabulary we use when we speak of young people or youth or young adults.

...

It remains to be seen how the usage of these terms may evolve over the next couple years. Regardless of how the words are used, it is important we don’t fall into a common problem described by Tony Vasinda of ProjectYM: “In the US, we have typically defined ministry to young people based on their age but not where they are on their spiritual journey.” While this “age-based” approach can have benefits in fields such as education or psychology, it fails when it defines our pastoral practice towards young people. One could argue that the continual debate about the most appropriate age for the Sacrament of Confirmation is a symptom of this issue.

There are seventeen-year-olds who are committed disciples of Jesus Christ; there are twenty-five-year-olds who are only just starting to think about their relationship with the Catholic Church. How might the Church give language to those pastorally accompanying such young people to guide them towards spiritual maturity?

AD: New Animated Christmas Movie in Theaters November 2017! Group Sales Available!

This is a paid advertisement in the October-December 2017 issue. Advertisements should not be viewed as endorsements from the publisher. To watch the trailer and to learn more go here. To inquire about group sales in your local area fill out this form.

Best Friends: Peer Groups and the Moral Life

When I had an opportunity to return to study in England after many years of active missionary life in East Africa, I took the opportunity to investigate the phenomenon of “school strikes” in Kenya in the hope of understanding what they were saying about moral decision making in adolescents. The school strike is a problem that has bedevilled Kenyan schools for many years, leading even to loss of lives and causing enormous damage to property. Many an education have been compromised by school strikes, which are basically student protests—often violent and destructive—against perceived injustices in the school system.

My own interest was primarily derived from a personal experience of a school strike that had taken place in the girls’ boarding school where I was working. Although no physical harm came to anyone, nor was there any damage to property, relationships between the staff and among the students themselves were strained, because many students were not even involved in the strike. It was difficult to simply return to a “business as usual” approach when there were so many unanswered questions surrounding the underlying reasons for the strike; the trust that had previously characterized our relationships had now been compromised. When asked afterwards—one by one in front of their parents—what grievance had provoked the strike, most of the girls had simply shrugged their shoulders and mumbled the word “influence.” Only some three or four felt they had some genuine reasons for protest but their influence had been strong enough to prevail over the majority.

As I investigated this phenomenon further with the participation of students from a number of other schools, layers of meaning were gradually uncovered. At surface level, a mistrust of authority emerged, expressed as outrage against the neglect and lack of concern for the welfare of the students demonstrated by school administrations in general. This was coupled with a sense of anonymity; one was known only by one’s peers but not by any significant adult within the school context. At a still deeper level, however, there emerged a much more preoccupying issue: a lack of a sense of life’s meaning and purpose that might guide moral decision making.

The most striking conclusion of the research was that, although most of the students were at least nominally Christian and many Catholic, very few of the students were influenced by their Christian faith. Their decisions were effectively pragmatic, a response to circumstances but without any reasoned consideration derived from principle.

Greater Love Hath No Hobbit

J.R.R. Tolkien’s monumental fantasy novels, The Hobbit (1937) and The Lord of the Rings (1954-55), have a great deal to teach about friendship. Many readers first encounter these works in adolescence, when our first encounters with friendship are forged—and, unfortunately, tested and maybe broken—by fallen humanity.

But even if we first came to Tolkien in adulthood, we can recognize the appeal of his stories to the notion of fellowship. The appeal lasts not only because the book presents shining images of stalwart friendships among its characters, but also because the book itself can be a friend in moments of friendlessness.

I’m not suggesting that the solace of a great book like The Lord of the Rings can ever replace the incarnate personhood of human beings that true friendship requires. But I think that the reason it seems like it can is that Tolkien gives us literary friendships that can seem more real than our “merely human” ones because of Tolkien’s Catholic conviction that there is a transcendent grace that lifts the “merely Hobbit” or “merely Elvish” friendships out of their mundane limitations.

Many Tolkien scholars have argued that Tolkien’s fantasy is successful because he can convince the reader that elves and rings of power and seeing-stones and wizards are real. But I think that the greatest literary magic of Tolkien is his ability—founded on his fervent belief—to convince the reader that friendships that cannot be broken by the fires of hell really exist.