Applied Theology of the Body: Purity of Heart and Sexual Modesty

Pope St. John Paul II devoted about 30 percent of his Theology of the Body (TOB) Catechesis (TOB 24–64) to extensive reflections on Jesus’s teaching in Matthew 5:27–28 regarding the need to avoid “lust” in the recesses of the human heart. St. John Paul II did not focus so intently on this teaching simply to hammer home the evils of lust. Instead, he saw lust as an acute threat to the divine plan for human love, and that plan for love was always his greatest concern. He repeatedly presents the teaching of Jesus not so much as a condemnation of our lustful hearts but as a call to purity of heart for the sake of purified love (TOB 42–59).

St. John Paul II utilizes St. Paul’s teaching that we must “abstain from unchastity” and “keep” the body “with holiness and reverence” (1 Thes 4:3–5) to emphasize that purity of heart has a “more positive than negative” dimension (TOB 54:1–3). Purity necessarily means being free from pollutants that contaminate the heart, but it should never be misconstrued as prudishness or disdain for the sexuality of the body (TOB 44:5–45:3). Authentic purity is found in a positive orientation of the heart that heightens our sense of the dignity and beauty of human sexuality in ourselves and in others.

This whole outlook on purity corresponds with what St. John Paul II calls the “ethos of redemption” (TOB 51:5) and the “life ‘according to the Spirit’” that make the reality of purified love “a new ability of the human being in whom the gift of the Holy Spirit bears fruit” (TOB 56:1). Instead of being anything we can manufacture for ourselves, true purity is given to us “by the power of Christ himself working in man’s innermost [being] through the Holy Spirit” (TOB 51:3). Through re-creation in Christ, we can be given a supernatural outlook on sexuality and new paradigms for our sexual lives.

This installment of the series presents the TOB teachings on purity of heart and sexual modesty as guideposts on the path of re-creation within the relationship of man and woman. These teachings help us better understand how our attitudes, thoughts, and desires should be impacted by God’s grace; from there, we can formulate a kind of checklist of God’s expectations for our sexual lives.

Light, Dew, and Fire: When Catechesis Is Attentive to the Holy Spirit

The Holy Spirit and the Deification of the Faithful

In Jesus’ Good Shepherd discourse, he describes his and his Father’s shared omnipotence as shepherd over his flock, saying that no one can claim the sheep either in his hand or in the Father’s hand, adding that he and the Father “are one” (Jn 10:30). Many of those around him prepare to stone him to death on the spot because they perceive this claim to be blasphemous. He does not, however, respond to the raging crowd in the manner we might expect theologically.

After briefly pointing to the authority of the works he does as bearing witness to his divine origin from the Father, Jesus directs the crowd to the absolute authority of the Psalms, which makes the same claim, “you are gods” (Jn 10:34, cf. Ps 82:6). He interrupts himself to add a crucial point: “Scripture cannot be nullified.” Jesus here illustrates an important biblical principle: one cannot simply ignore a difficult passage, even one that seems to be calling human beings “gods.” What results is a beautiful a fortiori argument: If Scripture calls them “gods,” how much more ought no one to object that Jesus, the Son of God, claims oneness with the Father. The crowd has no word to respond to this claim.[1]

How do we understand this claim, “you are gods”? Put simply, the Holy Spirit makes gods of the worshipping faithful. This is what St. Peter illustrates in one of his epistles when he writes that we are made to be “partakers of the divine nature” (2 Pet 1:4). We know from the rest of the Gospel of John and the consequent Tradition that implied in the Son’s claim about his union with the Father is the reality that the Holy Spirit effects a similar union between believers and God. So, when we are deified, or made divine, does that mean that we cease to be human? To borrow a phrase from St. Paul, by no means! That is the good news about deification—we remain fully human when we are made divine.

So how then are we made divine without the annihilation of our humanity? To answer that question, we need to turn to the Fathers of the Church, who give us some important foundational principles. They especially help to illumine the divinization of humanity. St. Irenaeus of Lyons, whom Pope Francis named a Doctor of the Church, puts it this way: “the only true and steadfast Teacher, the Word of God, our Lord Jesus Christ, . . . did, through His transcendent love, become what we are, that He might bring us to be even what He is Himself.”[2] Athanasius formulated the same principle when he said, “He was incarnate that we might be made God.”[3] This divinization, or theosis, does not obliterate human nature. Instead, human nature is elevated and filled with divine life.[4] Taking the lead from the Fathers, our understanding of this doctrine of deification is fundamentally Christ-centered. The extent to which God became man is the extent to which man becomes God. Though our “person” never becomes God, the good news is that we are radically elevated into supernatural life through the gift of the Spirit.

The conciliar tradition helps us to see the importance of humanity’s unchanging nature, especially in light of the definition of the hypostatic union at the Council of Chalcedon of 451. In this definition, we confess that the divine and human natures of Christ are united in the Son’s one hypostasis (that is, person) “without confusion, without change, without division, without separation.” This understanding of the union between the divine and human natures in Christ is crucial for our understanding how our humanity could be filled with divine life without undergoing an essential change. For example, in the Eucharist, the bread and wine are changed substantially into the body, blood, soul, and divinity of Christ. We call this change transubstantiation because only the accidental qualities of bread and wine remain, while the essence itself is changed. We are not “transubstantiated,” so to speak, in theosis.

The Holy Spirit in God’s Plan of Salvation

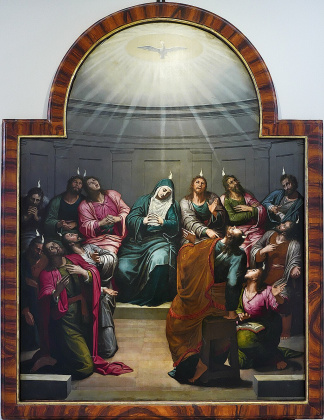

Pentecost, the sending of the Holy Spirit, ushered in the final stage of God’s plan of salvation.

Pentecost, the sending of the Holy Spirit, ushered in the final stage of God’s plan of salvation.

Editor's Reflections: The Holy Spirit and Our Free Response

“If we can nurture in a [person] the emergence and the victory of spiritual liberty, we have accomplished our task. If not, all is lost and the Christian life will weaken into childishness; it will harden into formalism; and finally it will disappear.” —Jean Mouroux, From Baptism to the Act of Faith

AD: Books by Pope Benedict XVI

This is a paid advertisement in the April 2023 issue. To find out more about these books, go to https://ignatius.com or call 800-631-1531.

Applied Theology of the Body: Fidelity and Indissolubility – A Lifetime of Unconditional Love

Pope St. John Paul II explicitly linked his Theology of the Body (TOB) catechesis[i] with the synod that he convoked to explore “the tasks that Christ gives to marriage and to the Christian family” (TOB 1:5). In his post-synodal document, Familiaris Consortio, he states, “To bear witness to the inestimable value of the indissolubility and fidelity of marriage is one of the most precious and most urgent tasks of Christian couples in our times.” In that same section of Familiaris Consortio, he specifically mentions the modern mentality that “openly mocks the commitment of spouses to fidelity,” and he calls on the whole Church “to reconfirm the good news of the definitive nature of that conjugal love that has in Christ its foundation and strength.”[ii]

St. John Paul II sensed an urgent need to uphold the complete fidelity and absolute indissolubility of marriage because he clearly understood that the most fundamental truths of the Gospel are at stake in these issues. He understood that the inherent dignity of the human person and our vocation to sacrificial, Christlike love are at stake in these issues. Ultimately, he understood that the issues of fidelity and indissolubility ask us whether we believe the Good News that, despite our concupiscence, humans are capable of unconditional love for an entire lifetime on account of our redemption in Jesus Christ. Conversely, St. John Paul II saw temptations to infidelity and divorce as manifestations of our concupiscence, with calls to change the doctrines of our faith on these issues representing a tragic capitulation to sinfulness and human frailty in the face of life’s difficulties.

The previous installment of this series presented the interpersonal meaning of the unitive aspect of marriage embedded in St. John Paul II’s reflections on marital consent. Interpreted through the lens of TOB, marital consent uniquely affirms the worth of the person by declaring, “I acknowledge you as my spouse and give myself to you fully and unconditionally all the days of my life. Being with you in this way is worth the gift of my whole life because you are worth the gift of my whole life. I renounce all others to be with you and you alone in this way because you are utterly unique and irreplaceable and worth sacrificing all others.”

To continue that theme, this installment of the series focuses on the fidelity (“I renounce all others to be with you and you alone”) and indissolubility (“all the days of my life”) required to live out this proclamation of worth in the daily life of the couple. We will also consider the spiritual truths at stake in these issues.

A Half Century of Progress: The Church’s Ministry of Catechesis, Part Six

The General Directory for Catechesis (1997) and the National Directory for Catechesis (2005)

General Directory for Catechesis (1997)

In light of the publication of the Catechism, it was decided that the General Catechetical Directory (GCD) was in need of revision. A portion of the task was given to the Congregation for the Clergy’s International Catechetical Commission (COINCAT). Even before the members and experts of COINCAT gathered, a thorough, international consultation on the proposed revision of the GCD had been conducted. The presidents of episcopal conference catechetical commissions, representatives of catechetical institutes and organizations throughout the world, and the members of COINCAT were asked to respond to a series of specific questions relating to a proposed revision of the GCD. Those responses were collated by the staff of the Congregation for the Clergy and woven into the Instrumentum Laboris, a document over seventy pages in length. The Instrumentum Laboris reflected three fundamental perspectives on the proposed revision of the GCD. The first seemed to advise only a slight revision, the second a moderate revision, and the third a more substantial rewrite.

The Ninth Plenary Session of COINCAT was held in Rome in September of 1994. Jose Cardinal Sanchez, prefect of the Congregation for the Clergy and president of COINCAT, called upon Archbishop Sepe, the Congregation’s secretary, to provide the more specific outline of COINCAT’s work for the week. In this outline, Archbishop Sepe first addressed the necessity for the revision of the GCD. He noted that it had been almost twenty-five years since its publication, that several important magisterial documents had been issued, and that much renewal had been undertaken within the ministry of the Word. He also pointed out that the pope had issued the call for a “New Evangelization,” that there had been significant development in the catechetical sciences, and that the Catechism had been recently published. Quoting Pope John Paul II in Catechesi Tradendae, Archbishop Sepe underscored the importance of the GCD and the need for its revision: “a Directory remains a fundamental document for the stimulation and orientation of the renewal of catechesis in the whole Church . . . it remains the norm of reference.”[1]

Archbishop Sepe then provided the parameters for the revision of the GCD. Based on the findings of the surveys, a moderate revision was indicated. That meant that all material that remained useful and relevant would be included in the revision; the universal character of the document would be preserved; and the information contained in magisterial documents published after the GCD would be incorporated where possible. Also, the Catechism would thoroughly inform the revision.[2]

The provisional scheme for the revised GCD has an introduction, five parts, and a conclusion. The general outline is as follows:

Introduction: The Purpose of the General Catechetical Directory

Part One: The Ministry of the Word of God

Part Two: The Christian Message

Part Three: The Pedagogy of the Faith

Part Four: Those to Whom the Catechesis Is Directed

Part Five: Catechesis in the Pastoral Action of the Church

Conclusion: Catechesis: The Work of the Holy Spirit[3]

The work of revising the GCD was divided into three main segments: Part One and the conclusion, Parts Two and Three, and Parts Four and Five, with one day of COINCAT’s plenary session spent on each. The last day would be spent formulating a table of contents for the revised Directory and suggesting the next steps to take for the timely completion of the project.

To this provisional scheme the working group added some criteria for redaction of the GCD. These criteria did not have the benefit of revision within the working group because there simply was not enough time to do so. Therefore, the criteria were understood as a provisional first draft subject to later revision. They were as follows:

- Continuity and enrichment. The present General Catechetical Directory comes with valuable elements. We should seek improvement by adding that which seems to be necessary.

- Be mindful of events that followed the publication of the General Catechetical Directory in 1971: the two synods regarding catechesis; the apostolic exhortations Evangelii Nuntiandi and Catechesi Tradendae; the 1983 Code of Canon Law; the encyclicals Redemptoris Missio and Veritatis Splendor; and finally, the publication of the Catechism.

- In the new structure of the General Catechetical Directory there are elements that should be replaced in view of a new synthetic ordering.

- Literal citations of the documents of the Magisterium should be placed in the new text.

- The four parts should be presented as criteria of the unity of life in Christ, the aim of catechesis.[4]

The Spiritual Life: The Eucharist – Food of Truth and Source of our Salvation

In a 1978 Lenten catechesis given in Munich, then-Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger spoke of the eucharistic mystery as an incomparable encapsulation of Christ’s transformative self-gift, whose meaning is best expressed in the act of washing his disciples’ feet: “He, who is Lord, comes down to us; he lays aside the gar

In a 1978 Lenten catechesis given in Munich, then-Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger spoke of the eucharistic mystery as an incomparable encapsulation of Christ’s transformative self-gift, whose meaning is best expressed in the act of washing his disciples’ feet: “He, who is Lord, comes down to us; he lays aside the gar

In the Form of a Sacrificial Meal: The Sacrifice of Calvary and the Sacrifice of the Mass

For an average Catholic, even one who speaks piously of the Mass as the re-presentation of the sacrifice of Calvary, the link between Christ’s dramatic death on the Cross can seem remote from the sacred liturgy’s formal ritual. The notion of the Mass as a sacred meal comes from its roots in the Last Supper, and the Eucharistic Prayer conspicuously repeats the very words of Christ at the Passover meal of the Upper Room. But historically, the Mass is also called a sacrifice. Even the Second Vatican Council’s constitution on the liturgy, Sacrosanctum Concilium, calls the Mass a sacrifice nine times and urges the laity to join themselves to the sacrifice offered by the priest. Yet, sacrifice of the ancient type is utterly unfamiliar to the modern world. Though its mechanisms are on vivid display in the Mass and its priestly and sacrificial logic is present, the sacrificial aspects of the Eucharist can seem only opaquely present rather than radiantly and fruitfully perceived. A little-known book by an author of great intellect provides a helpful interpretive guide in seeing how the Mass makes present the sacrifice of Christ: Jean Hani’s The Divine Liturgy: Insights into Its Mystery.[1]

For an average Catholic, even one who speaks piously of the Mass as the re-presentation of the sacrifice of Calvary, the link between Christ’s dramatic death on the Cross can seem remote from the sacred liturgy’s formal ritual. The notion of the Mass as a sacred meal comes from its roots in the Last Supper, and the Eucharistic Prayer conspicuously repeats the very words of Christ at the Passover meal of the Upper Room. But historically, the Mass is also called a sacrifice. Even the Second Vatican Council’s constitution on the liturgy, Sacrosanctum Concilium, calls the Mass a sacrifice nine times and urges the laity to join themselves to the sacrifice offered by the priest. Yet, sacrifice of the ancient type is utterly unfamiliar to the modern world. Though its mechanisms are on vivid display in the Mass and its priestly and sacrificial logic is present, the sacrificial aspects of the Eucharist can seem only opaquely present rather than radiantly and fruitfully perceived. A little-known book by an author of great intellect provides a helpful interpretive guide in seeing how the Mass makes present the sacrifice of Christ: Jean Hani’s The Divine Liturgy: Insights into Its Mystery.[1]

A professor at the University of Amiens in France, Hani’s academic specialty was comparative religions, studying ancient cultures steeped in sacrifice, including Judaism. A Catholic himself, Hani was interested in revivifying Catholic worship by reengaging it with its sacrificial origins in order to counter what he called the “sterilization of the imaginative side” of Christianity (4). For teachers and preachers today, his insights can help lead believers into a deeper understanding of the words of the Council that tie together both meal and sacrifice in the Mass: “At the Last Supper . . . our Savior instituted the eucharistic sacrifice of His Body and Blood . . . to perpetuate the sacrifice of the Cross throughout the centuries until He should come again, and so to entrust to His beloved spouse, the Church, a memorial of His death and resurrection.”[2]

The Nature of Sacrifice

The English word sacrifice comes from two Latin roots, sacra, meaning “holy” or “sacred,” and facere, meaning “to make” or “to do.” So, the goal of any sacrifice is to do the sacred action with the intent of making things holy. Hani rightly establishes why the Mass is indeed a sacrifice: it re-presents and makes real the sacrifice of Christ in order to make creation holy again after the Fall. By immolating a victim, literally “grinding” it up (from Latin molere, “to grind”), two ends were hoped for: reconciliation, which means being friendly again after a division, and propitiation, gaining or regaining the favor of another (7). In Christ’s case, his perfect self-offering did both: it healed the relationship between God and man perfectly, then made it possible to receive God’s sanctifying grace. In Eden, logically, humans had no need to offer sacrifice since the relationship between God and man had not yet been wounded by the Fall. And so Hani notes, “man quite naturally made that gift to God which is the obligatory response of the creature to the Creator, an absolutely pure gift, entirely spiritual: the gift of the heart” (14). After the Fall, however, humans no longer had the capacity for perfect spiritual giving. So, in his mercy, God “imparted to man the sacrifice [he] desired and determined . . . as a way of remedying this spiritual catastrophe” (14). In other words, God himself taught man how and why to offer sacrifice.

To show how the Mass fulfills the Old Testament requirements, Hani explains the complex array of Jewish sacrifices (8–11). Some were bloodless, such as the minha, with its flat breads made of flour and oil, some of which were burned completely and some eaten by priests on the Sabbath. Others were blood sacrifices, such as the holocaust, or olah, in which a bull was bled to death and then totally consumed by fire. The Sacrifice of Peace, or zebah shelamin, was a communion sacrifice in which the blood and fat of an animal was burned completely, while the rest was served for both priests and the faithful at a banquet. Notably, at the moment of communion with the flesh of the animal, Psalm 116 was read: “What shall I render unto the Lord for his goodness to me? I will take the cup of salvation and call upon the Name of the Lord,” a psalm later introduced to the Mass, recited by the priest after receiving the host. The most important Jewish feast was Passover, also a communion sacrifice, which involved the sacrifice of a paschal lamb both at the Temple and in individual homes, followed by a meal in which the victim was eaten in remembrance of the passage of the Israelites to the Promised Land. In other words, it became sign of passage from death to new life, answering the need established in Eden generations earlier.

In each case, the sacrifices involved immolation, death, and new life. Most evident is the holocaust, in which blood, which represents life, was drained from the animal’s body, then its flesh consumed by fire. The resulting smoke was said to take the sacrifice to heaven and therefore to God. Even the seemingly innocuous bloodless sacrifice of flat breads involved immolation through the grinding up of grains of wheat. Moreover, the twelve breads represented the twelve tribes of Israel (8), and so burning some and consuming others gave it overtones of holocaust and communion. In each case, the things sacrificed stood in for people, and after it was offered, it was eaten in a ritual meal. So when Christ equated the sacrifice of his own body with the breaking of bread—and thereby linking sacrifice with a meal—it would have been both strangely familiar and yet shockingly new. Christ was now priest and victim.