The Spiritual Life: God, Who are You?

Have you ever wondered why Jesus’ disciples found it so difficult to grasp his true identity, even after living so closely with him and directly witnessing his great works?

Have you ever wondered why Jesus’ disciples found it so difficult to grasp his true identity, even after living so closely with him and directly witnessing his great works?

A Pagan Poet in Our Eucharistic Prayers

St. Paul did his homework carefully before proclaiming Christ to the Athenians. It paid off. In Acts 17, we find St.

St. Paul did his homework carefully before proclaiming Christ to the Athenians. It paid off. In Acts 17, we find St.

Jewish Oral Law and Catholic Sacred Tradition

I like to say that studying Judaism made me Catholic. Many years ago, I was a zealous, anti-Catholic evangelical Christian living in Jerusalem and active in the Messianic Jewish movement (the movement of Jews who believe in Jesus). Messianic believers are eager to rediscover the Jewish Jesus and the Jewish practices of the Early Church before it became tainted and compromised—so they say—with gentile beliefs and practices.

Like my Messianic Jewish friends, I accepted as the foundation of my faith the principle of sola scriptura—the great theological pillar of the Reformation positing that the Bible is our only and final source of authority in matters of faith. According to the Reformers and their followers, because human traditions are unreliable and prone to change, the Bible alone is the trustworthy Word of God that communicates to us the eternal truths that God revealed for our salvation (cf. 2 Tm 3:16).

Yet after spending a few years in the Messianic movement, I began to feel uneasy about sola scriptura. I found the doctrinal anarchy reigning in Protestantism and in Messianic Judaism increasingly disturbing. Even though all believers accepted the Bible as the Word of God, they constantly disagreed among themselves on substantial points of doctrine, with no final authority able to arbitrate between them. I began to think, moreover, that the endless multiplication of denominations found in Protestantism could surely not be God’s will. This led me to investigate what Scripture and Judaism had to say about the nature of God’s revelation to man.

Recovering Nature and Building Culture in Catechesis

It is not a secret that knowledge of the faith continues to decline. It is tempting to insist simply upon teaching more doctrine, but this overlooks a more fundamental problem. What is catechesis really about? It is not simply knowledge of the faith but knowledge of the living God, a knowledge that includes and goes beyond simply the intellect, as it must include a complete transformation of life. We are not simply missing knowledge of the faith but the entire structure of life and culture that should undergird and support this knowledge.

The Cultural Foundation for Catechesis

Grace builds upon nature, according to the scholastic adage. By “nature,” we mean the natural foundation of human life—our ability to think, make free choices, and order our lives through good habits. Even more foundationally, nature refers the basic soil of human potential that God uses to draw forth his divine fruit. But how would we describe the “state of nature” today? It is not a stretch to say that the soil of human life has worn thin through the saturation of technology and a fundamental change in the way we understand and relate to one another, mediated by a screen with less interpersonal contact. Catechesis has to compensate for these challenges, seeking to build up a more robust community to provide a stronger cultural context to receive the faith.

Just as grace builds upon nature, so faith builds upon culture. In fact, Pope St. John Paul II declared faith to be “incomplete” without a culture to live it out faithfully.[i] Culture is a shared way of life, one that is necessary because Christians need to live out their faith in communion with others. As we know from our own experience, it can be quite difficult to live the Christian life when you are pushing against the cultural currents. Perhaps our religious education has fallen short because we have not attended closely enough to the cultural dynamics of faith. Right thinking, healthy living, rightly ordered work, and robust community all contribute to building up the soil needed to support the Christian life.

The Eucharist: Source of Cultural Renewal

Western Culture needs renewal. This task of ennobling culture is vast indeed, and requires each of us to be a part of it. There are no sidelines or bystanders. It has been said that “Culture is the root of politics, and religion is the root of culture.”[i] To go a step further, religion rests upon the worship of God, and the Eucharist is at the center of true worship. Therefore, the task of ennobling culture requires ennobling religion and, correspondingly, ennobling worship, at the center of which we find the living God present in the Eucharist. Christian disciples must set Jesus Christ in the Eucharist at the center of their lives, as the Eucharist truly is the source and summit of that life,[ii] from whom flows rivers of living water (Jn 7:38), and apart from whom they cannot have life (Jn 6:53). The Eucharist celebrated and the Eucharist lived can transform our lives, the lives of others, and our culture itself.

Notes

[i] Fr. Richard Neuhaus, quoted in “Richard John Neuhaus Society,” First Things, https://www.firstthings.com/richard-john-neuhaus-society.

[ii] See Second Vatican Council, Lumen Gentium, no. 11.

Ennobling Human Culture

In his encyclical letter Redemptoris Missio, John Paul II makes the claim that “since culture is a human creation and is therefore marked by sin, it too needs to be ‘healed, ennobled and perfected’” (John Paul II, Redemptoris Missio, no. 54).

The Intellectual Backstory

Like many statements in ecclesial documents, one needs to know the intellectual history behind the statement above—the “backstory” as it were.

Here part of the backstory is the Romantic-era approach to the subject of culture, including the idea that every national group has its own culture and that each and every national culture is equally of value. In other words, it is a typical Romantic argument that no one culture is superior to another, all are of equal value.

Many people unreflectively adopt something like the Romantic approach because they have a memory of one particular culture (or anti-culture) trying to assert its superiority using tanks and aircraft bombers and gas chambers.

A Catholic theology of culture is, however, radically different from the Nazi ideology of culture. The Catholic vision has absolutely nothing to do with conceptions of racial superiority. Genetics has nothing to do with it. The Catholic conception is all about grace and how some human practices are more or less open to grace than others and thus some cultures are superior or more noble than others because they are more open to grace than others.

Since Catholics believe that all human beings are made in the image of God, whether they are born in one of the culturally sophisticated suburbs of Paris or in a village somewhere that has yet to obtain Wi-Fi, they all begin their lives with the same status before the throne of the Holy Trinity. In this sense the Catholic faith is both universal and egalitarian. Baptism does not recognize class distinctions. Once a person has been baptized they are a member of the Royal Priesthood. As the Orcadian Catholic writer George Mackay Brown poetically explained in his short story “The Treading of Grapes,” in heaven Christ will address his friends with the royal titles Prince and Princess. However, what Catholics do with the gift of their baptismal graces will have an impact upon their own nobility or lack of it, and upon their social practices and their culture. Those who are the most saintly are the most ennobled.

Editor's Reflections: Christians and Culture

Many readers of this journal are familiar with how John Paul II describes the definitive aim of catechesis. Our objective as teachers of the faith is to lead those we teach into communion, into real intimacy, with Jesus Christ.[1] He is not only to be our model and example. He is not merely our brother and friend. And he is not only our High Priest and Divine Teacher, revealing to us the right way to see reality and live within it.

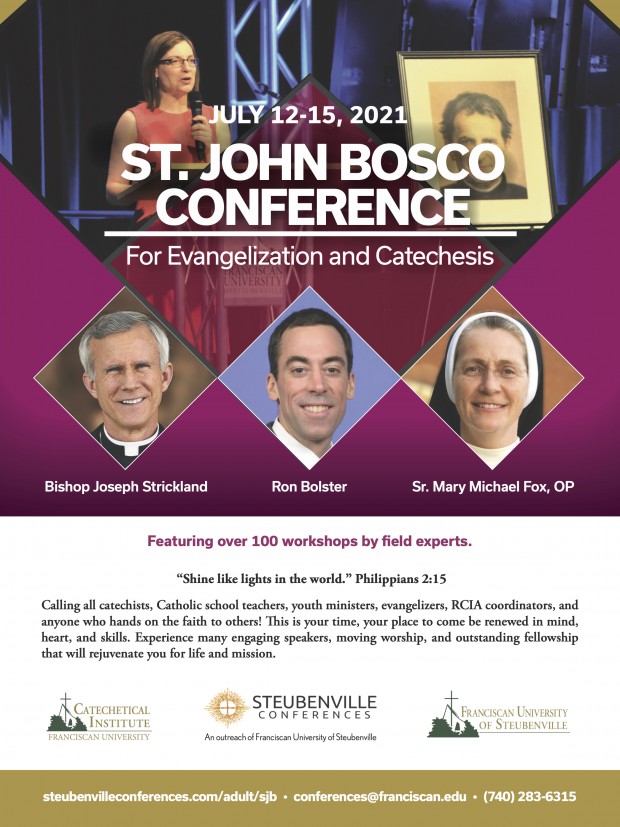

AD: Summer Conference for Catechists and Catholic School Teachers

Click here to learn more about this enriching conference with a wide array of speakers and topics.

El RICA adaptado para las familias: todo tiene que ver con los padres de familia: Primera Parte

“Porque la promesa ha sido hecha a ustedes y a sus hijos, y a todos aquellos que están lejos:

a cuantos el Señor, nuestro Dios, quiera llamar” (Hechos 2,39).

Tiempos desafiantes requieren de soluciones innovadoras. Estos son, en verdad, tiempos desafiantes, tanto en el mundo como en la Iglesia. Es importante que los catequistas laicos brillen como faros de luz en la oscuridad para atraer a familias enteras hacia la sola Luz verdadera – la del mismo Cristo en la Iglesia Católica. Más importante aún, es el momento para que el sabio proceso del RICA tome la delantera de nuestros esfuerzos para la evangelización y la catequesis de familias enteras.

Que lo reconozcamos o no, providencialmente nos hemos estado capacitando desde hace muchos años para este tiempo que ahora vivimos. La Santa Madre Iglesia cuida bien de sus hijos y nos ha estado preparando desde hace décadas. Desde la restauración del catecumenado bautismal del Concilio Vaticano II [1] al Directorio General para la Catequesis [2], el Directorio Nacional para la Catequesis [National Directory for Catechesis] [3], y, más recientemente al recién publicado Directorio para la Catequesis[4], la Iglesia ha sostenido al catecumenado bautismal como modelo esencial sobre él que debe de basarse toda la catequesis.

El nuevo Directorio para la Catequesis declara que “la inspiración catecumenal de la catequesis … se hace cada vez más urgente recuperar” (DC 2). ¿Qué tiene el RICA que lo hace ser un modelo tan inspirador? El nuevo Directorio nos ilumina: “Tal experiencia formativa es progresiva y dinámica, rica de signos y lenguajes, favorables para la integración de todas las dimensiones de la persona” (DC 2).

Al desentrañar esta declaración magisterial, comenzamos a ver el beneficio que proporciona el hacer uso del modelo catecumenal para formar a discípulos de todas las edades. El RICA es una experiencia que moldea y forma, promoviendo un cambio desde quién sea la persona en el momento presente hacia la persona para la que Dios la creó. Este cambio, o metanoia, pretende ser algo muy poderoso y energizante para el participante. Involucra mucho más que una asistencia pasiva a las sesiones “saltando por todos los aros” para recibir un certificado de finalización al concluir el programa. Un programa tiene un principio y un fin, mientras que un proceso es algo fluido y continuo. El proceso del RICA es diseñado para renovar y traer a la unión cada aspecto de la persona con Cristo y Su Iglesia para toda la eternidad. Este cambio le costará algo a cada participante. La manera en que él o ella ha vivido la vida en el pasado ahora cambiará de muchas maneras, lo cual puede ser más que un poco desconcertante. Los signos y las expresiones no pueden ser percibidos como “ricos” hasta que la persona comience a cambiar y busca aprender y comprender cómo se mueve Dios en su alma. A cada persona se le debe de otorgar el tiempo necesario aunado al acompañamiento de discípulos formados “para sentirse llamados a alejarse del pecado y atraídos hacia el misterio del amor de Dios” cuando comienzan a desear seguir a Cristo. [5]

Extensión misionera

En lo profundo de las trincheras de la vida parroquial, nuestro equipo de RICA ha recién comenzado lo que mejor se puede describir como una extensión misionera hacia los padres de familia que se acercan a la Madre Iglesia con sus hijos no bautizados quienes tengan desde la edad de la razón hasta cumplir los diecisiete años. En el pasado, nos hubiéramos enfocado principalmente en la preparación de estos jóvenes por medio del proceso de RICA adaptado para niños y jóvenes. Mientras que afirmamos que es una obra valiosa de por sí, hemos descubierto a través de la experiencia que con frecuencia termina siendo un callejón sin salida desde el punto de vista catequético y espiritual.

Lo más común es que los mismos padres de familia no hayan sido evangelizados, y si lo han sido, han pasado muchos años desde que recibieron cualquier formación en la Fe. Esto, sumado al hecho de que rara vez asisten a Misa (si es que siquiera asisten), no son parte activa de la comunidad parroquial, y a menudo se encuentran en situaciones matrimoniales irregulares, hace que sea más esencial enfocar a los padres de familia, además de sus hijos chicos y adolescentes. Dicho de otra manera, si no atendemos a los padres adultos, sea cual sea su situación, los niños no podrán practicar su Fe en la comunidad en la cual son acogidos porque nunca más los volveremos a ver. Reciben sus sacramentos, y “allí quedan” – con frecuencia de por vida, debido a la falta de apoyo espiritual en el hogar.

RCIA & Adult Faith Formation: RCIA Adapted for Families—It’s All About the Parents, Part One

“For the promise is to you and to your children and to all that are far off, every one whom the Lord our God calls to him.” Acts 2:39

Challenging times require innovative solutions. These are indeed challenging times, both in our world and in the Church. It is important for lay catechists to shine as beacons of light in the darkness to draw entire families to the one, true Light—that of Christ himself in the Catholic Church. Most importantly, it is the time for the wise process of the RCIA to move to the forefront of our endeavors for the evangelization and catechesis of entire families.

Whether we realize it or not, we have providentially been training many years for the time in which we are now living. Holy Mother Church takes good care of her children and she has been preparing us for decades. From the restoration of the baptismal catechumenate at Vatican II[1] to the General Directory for Catechesis,[2] the National Directory for Catechesis,[3] and most recently to the newly published Directory for Catechesis,[4] the Church has held up the baptismal catechumenate as the essential model upon which all catechesis should be based.

The new Directory for Catechesis states that it “is becoming ever more urgent, that catechesis should be inspired by the catechumenal model” (DC 62). What is it about the RCIA that makes it such an inspiring model? The new Directory enlightens us: “This formative experience is progressive and dynamic; rich in signs and expressions and beneficial for the integration of every dimension of the person” (DC 2).

Unpacking this magisterial statement, we begin to see the benefit of using the catechumenal model to form disciples of all ages. The RCIA is a shaping or forming experience that advocates a change from who the person is at present toward the person God created him to be. This change, or metanoia, is meant to be very powerful and energizing for the participant. It involves much more than passively attending sessions to jump through hoops and receive a certificate of completion at the end. A program has a beginning and an end, whereas a process is fluid and ongoing. The RCIA process is designed to renew and bring into union every aspect of the person with Christ and his Church for all eternity. This change is going to cost each participant something. The way he or she has lived life in the past will now change in many ways, which can be more than a bit unnerving. The signs and expressions cannot be perceived as “rich” until the person begins to change and seeks to learn and understand how God moves in his or her soul. Each individual needs to be given the necessary time coupled with accompaniment by formed disciples to “to feel called away from sin and drawn into the mystery of God’s love” as they begin to desire to follow Christ.[5]

Missionary Outreach

Deep in the trenches of parish life, our RCIA team has recently begun what may best be described as a missionary outreach to parents approaching Mother Church with their unbaptized children who have reached the age of reason through age seventeen. In the past, we would have focused primarily on preparing these young people via the RCIA process adapted for children and teens. Albeit a worthy endeavor in itself, we have found through experience that it often ends up being both a catechetical and spiritual dead end.

Most often, the parents have never been evangelized themselves, and if they have been catechized, it has been many years since they have received any formation in the faith. This, coupled with the fact they rarely attend Mass (if at all), are not an active part of the parish community, and often have irregular marriage situations, makes it all the more essential to focus on the parents as well as their children and teens. In other words, if we do not minister to the adult parents in whatever situation they happen to be, the children will be unable to practice their faith in the community to which they have been welcomed because we will never see them again. They receive their sacraments, and they are “done”—often for life, due to the lack of spiritual support in the home.