Penance as Devotion

“Dad, why does God like it when I suffer? I don’t like it.” This was the question that my five-year-old, Anastasia, posed during a recent dinner at home. As the liturgical seasons ebb and flow and certain penitential days make their appearance (not to mention the year-round meatless Fridays), my wife and I frequently encourage our three little children to offer some small, age-appropriate sacrifices to God. These exhortations, however, gave my little Anastasia the idea that God takes delight in our suffering—a long-debated question spanning multiple creeds. But is it true? If I put up with cold, or heat, or hunger, or that annoying co-worker, does God really find joy in my discomfort? What about people with cancer or any other painful illness? Ultimately, does God take delight in my death?

Children's Catechesis: Leading Children to Hear the Call of God

Recently, a local parish invited me to speak on a panel on vocations for middle and high schoolers. At most of these events, the questions usually include, “What is your day like?” “How often do you see your family?” and “What do you do for fun?” At this parish, the organizers left out a box for anonymous questions and didn’t screen them beforehand. Almost every question began with, “Why can’t I . . .” or “Why doesn’t the Church let me . . .” One of the monks on the panel leaned over and asked me, “Isn’t this supposed to be a vocations panel? Why are we even here?”

This experience opened my eyes to a reality: children and teenagers must know and love Jesus intimately as a person before anything we do to promote vocations will bear fruit. This intimacy is at the heart of all vocations, because at baptism God gives each person a share in his divine life, calling the Christian to a life of holiness. It’s within the context of a healthy family life that children first experience this love of God as well as the virtues and dispositions that serve as a remote preparation for their particular vocations.[1]

Thank God for Pain

How much worse off we would all be without physical pain! As counterintuitive as it sounds, pain is your friend. Pain is a mechanism to warn you that something is wrong. Imagine a scenario where there was no physical pain. When you get sick with a virus, you don’t feel bad, so you don’t take care of yourself. The virus spreads rapidly because there is no way to know that you have it until it is too late. Death or relentless monitoring become the only two ways to know that something is physically awry. Who would want to live like that? Dramatically shortened lifespans and constant paranoia? No thanks!

Twenty years ago, when I was first diagnosed with cancer, it was pain that made me go see a doctor. Thank goodness the pain arrived in time! The doctors found the cancer and treated it before it was too late. I’ve received 20 additional years on this good earth because of this good friend, pain. If it weren’t for pain, I wouldn’t be alive to write this today. I am grateful!

Because it is so familiar, physical pain is no longer very intimidating to me. Of course I don’t like it, but it’s manageable. Besides alerting me to something being amiss, it is helpful because it is purifying. It calls me to something higher. For instance, when a tech comes into my hospital room to wake me up in the middle of the night to draw blood, I am challenged to respond with kindness and docility. She appears abruptly with a bright light and sharp needle to do her job. This is rather unpleasant for me, but it’s also for my good. The least I can do is be pleasant to her regardless of how I am feeling. Subtle sighs or groans of annoyance or self-pity only serve to assault her with an air of needless negativity. What good does that do? I admit that sometimes I fail, but the pain offers me a great opportunity. It calls me to become the best version of myself.

Attaching to Mary: The Gesture of Pilgrimage

I come here often. Sometimes I come in gratitude. Other times I come here to beg. I come alone. I come with my wife and our kids.

Growing up, it took thirty minutes to get here. Back country roads. Flat. Everything level and straight. Fields speckled with the occasional woods, a barn, a farmhouse. It was practically in my backyard. But then I moved. Now, it takes about three hours. I drive up the long interstate to those familiar country roads that lead into the village.

The sleepy, two-stoplight town is something of a time warp. Life just moves slower in Carey, Ohio. The rural way of life is simpler than the suburban variety.

I stay for hours, or for twenty minutes. Being here is all that matters.

Yes, I come here often. It’s in my blood.

I am a pilgrim.

Basilica and National Shrine of Our Lady of Consolation

In June of 1873, Fr. Joseph Peter Gloden was entrusted with the mission in Carey, Ohio: thirteen families and an unfinished church building. The people were discouraged. But Fr. Gloden rallied the small band of Catholics, and the nascent congregation finished the construction of the church. It was given the title Our Lady of Consolation, for, as Gloden said, “We are not yet at the end of our difficulties and we need a good, loving and powerful comforter.”[1]

After the church was dedicated, Gloden, originally from Remerschen, Luxembourg, sought to obtain a copy of the statue of Luxembourg’s Our Lady of Consolation. The statue was made of oak and adorned with a fabric dress. The replica of the statue from the Cathedral of Luxembourg arrived in Carey in March 1875. To give Our Lady’s statue a most solemn entrance into her new home, Fr. Gloden and his parishioners decided on a seven-mile procession to the church in Carey from the nearby parish in Frenchtown, Ohio.

The big event was to take place on May 24, 1875. The day before, a heavy storm swept through the area. On the morning of the proposed procession, another storm threatened. Lightning could be seen across the horizon. Gloden urged the crowd not to scatter, calling out, “Let the procession proceed; there is no danger.”[2] And so they charged into a thunderstorm. The rest is history. Rain poured all around the procession, but nobody in the procession got wet. Once the statue reached the church and was safely inside, the rain pelted the earth.[3] From the beginning, the whole thing was viewed as a miraculous event—a light prelude to events that would happen in Fatima some decades later. On that day in rural Ohio, Mary protected her beloved little ones from the elements.

Lessons Lourdes Offers to Evangelists and Catechists

Many were the attempts made in Europe during the nineteenth century to redefine and refashion human existence. Significantly, over the same period there were three major apparitions in which Mary, Mother of the Redeemer, was present: Rue du Bac in Paris, France (1830); Lourdes, France (1858); and Knock, Ireland (1879). Taken together, these offer the answer to humanity’s searching. Let us look particularly at Mary’s eighteen apparitions to Bernadette Soubirous in Lourdes.

In February 1934, one year after Bernadette’s canonization, Msgr. Ronald Knox preached a sermon in which he compares the young girl’s experience with that of Moses, even suggesting we might see Lourdes as a modern-day Sinai.[1] We should note that the events on Sinai are at the heart of biblical revelation, whereas those in Lourdes were private revelations later acknowledged by the Church to be for our good; yet, Knox finds many similarities between the two. Both, for example, took place on the slopes of hills; Moses and Bernadette were shepherds at the time; for both, a solitary experience resulted in the gathering of great crowds. Moses took off his shoes out of reverence for holy ground; Bernadette removed hers to cross a mill stream. Each was made aware of a mysterious presence demanding their attention: for one, by a fire that burned but did not consume; for the other, at the sound of a strong wind that did not move trees and the sight of a bright light that did not dazzle.

Moses was to lead the people out of bondage, though the Hebrews fell back to the worship of a golden calf. Knox writes that Bernadette was also “sent to a world in bondage,” a bondage in which it rejoiced. He finds significance in the fact that her visions took place in the middle of the Victorian age, when material plenty had given rise to materialism, “a spirit which loves . . . and is content with the good things of this life, [which] does not know how to enlarge its horizons and think about eternity.” Bernadette “was sent to deliver us from that captivity of thought; to make us forget the idols of our prosperity, and learn afresh the meaning of suffering and the thirst for God.” “That,” Knox uncompromisingly affirms, “is what Lourdes is for; that is what Lourdes is about—the miracles are only a by-product.” The preacher has no doubt of our own need for this message: “We know that in this wilderness of drifting uncertainties, our modern world, we still cling to the old standard of values, still celebrate . . . the worship of the Golden Calf.”

Marian Devotion and the Renewal of Church Life

What happened to Mary? This is a question that could easily occur to anyone reading through 20th-century theology. Marian theology up to the 1960s was vibrant and flourishing. Fr. Edward O’Connor’s 1958 magisterial volume The Immaculate Conception (recently re-released by University of Notre Dame Press) seems to sum up an era. The lively essays harvest the best of traditional theology and seem poised to surge ahead, bursting as they are with both creativity and fidelity. And yet, ten years after its publication, Marian study was nearly dead. This book remains unsurpassed in its field.

What happened to Mary? This same question could be asked by anyone old enough to remember Marian piety before 1968, even if, as is more and more likely now, they were only children at the time of Vatican II, which closed that year. Marian piety had seemed so alive and well that it seemed unthinkable that it could be dislodged. But within ten years of the Council, it had all but vanished.

What happened to Mary? This same question is most likely not to be asked by Church members who grew up in the post-conciliar Church. The tragedy of any enduring loss is that eventually no one notices anything is missing. When one’s spiritual sensibilities have been dulled through lack of use, one lives an impoverished spiritual life without even realizing it. The question is not likely to occur to those born in the 70s or later, unless, perhaps, they travel to regions in the world or encounter subcultures within our own society where Marian devotion is alive and well. The encounter can almost seem shocking to the person whose spiritual sensibilities are thereby newly awakened. They might very well be prompted to ask, “But what happened to our Mary?”

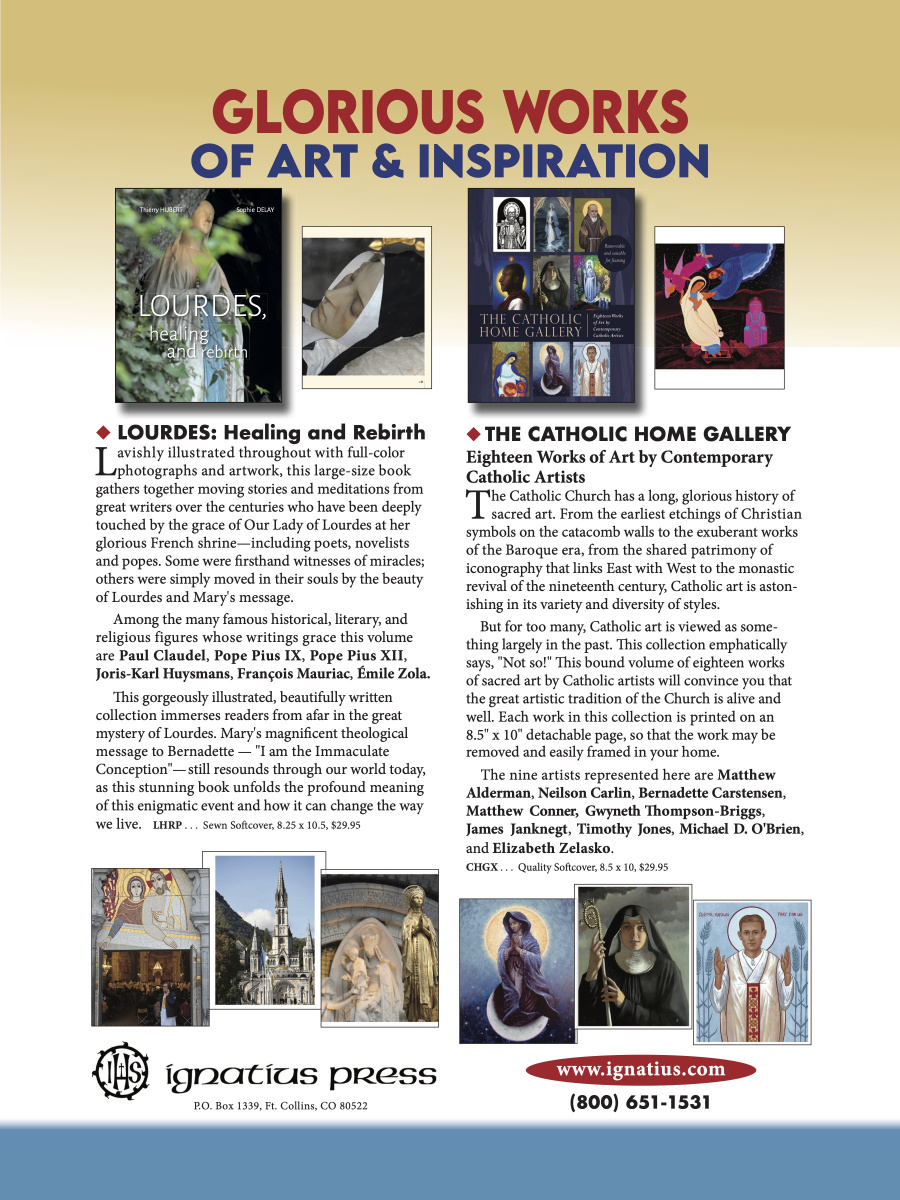

AD: Glorious Works of Art and Inspiration

This is a paid advertisement. To order these resources visit www.ignatius.com or call 800-651-1531.

Resting in the Lord: Liturgy and Education

In his important apostolic letter Dies Domini (“Keeping the Lord’s Day Holy”), St. John Paul II argues that to rest is to re-member (put together again) the sacred work of creation on the day set aside for worship, thus orienting times of rest toward a deeper contemplation of God’s vision of humanity. “Rest therefore acquires a sacred value: the faithful are called to rest not only as God rested, but to rest in the Lord, bringing the entire creation to him, in praise and thanksgiving, intimate as a child and friendly as a spouse.”[i]

The human need for rest is not a call for inaction or laziness. Times of rest need some form of activity to remove our minds and attachments from the workaday tasks that can too easily become heavy and uncomfortable burdens. St. John Paul II’s use of “in praise and thanksgiving” is shorthand for the celebration of the liturgy.

Embracing the Paschal Mystery

Liturgy, as the celebration of the Paschal Mystery, is the heart of Catholicism. It integrates the divine and the human, the active and the contemplative. “The Paschal mystery of Christ’s cross and Resurrection stands at the center of the Good News that the apostles, and the Church following them, are to proclaim to the world. God’s saving plan was accomplished ‘once for all’ by the redemptive death of his Son Jesus Christ” (CCC 571).

Note

[i] John Paul II, Dies Domini, no. 16.

Practical Strategies to Promote Vocations

Most of them didn’t go to Catholic schools. A quarter of them never served at Mass. Only about half were ever in a youth group, and a good chunk are converts. A majority of them are over 40 years old. One in three has no European ancestry. By statistical and anecdotal analyses, the newest priests of the United States come from varied, even surprising, backgrounds.[1]

The lack of sufficient vocations to the priesthood and religious life stands out as the preeminent practical challenge for the Church in our country today. We might opine at length about the theoretical causes of this crisis and the other related pastoral woes, strategic errors, and cultural forces with which we must contend, but the pressing imperative remains: We need more priests now, before the future unfolds far more bleakly. Band-aid solutions like merging parishes—in some places, parishes that are financially sound and demographically stable—or contracting foreign and religious clergy (blessings though they be) only serve to delay the inevitable and potentially disturb the faith of parishioners in the interim. The following suggestions only supplement the ongoing conversation to build a positive culture of healthier vocational discernment in the Church, our parishes, and the families from which the priests and religious of tomorrow are called.

Let’s Get Practical

Practical problems call for practical solutions. I often hear it said about the topic of vocations, “What can we do aside from pray?” Well-intended as that sentiment may be, we must believe firmly that imploring God’s grace through prayer remains the most fruitful tactic. It is his supernatural activity that accomplishes every good, especially the sublime gift of a holy vocation. Communal liturgies and devotions concretely bring people together and witness to the need, which can in turn inspire young hearts. I recall finding myself as a high school student in our parish’s perpetual adoration chapel praying the Rosary for more priestly vocations, and finally it hit me . . . it’s me!

Note

[1] The Ordination Class of 2023 Study provides the latest statistics from the United States Conference of Catholic Bishops in conjunction with the Center for Applied Research in the Apostolate: https://www.usccb.org/resources/ordination%20class%202023%20final%20repo...

The Spiritual Life: Poverty, Purity of Heart, & Eucharistic Living

This article is part of a 3-year series dedicated to promoting the efforts of the National Eucharistic Revival in the United States.

“The Body of Christ.” “Amen.” Each time we participate in Mass, we have the opportunity to encounter the Lord Jesus in the most intimate way through the reception of Holy Communion. This moment is the most practical and profound way we can live Jesus’ invitation to “abide in my love” (Jn 15:10) this side of heaven. Yet, this moment of communion is not solely about a personal bond with Jesus. The relationship with him—strengthened and nourished by the Eucharist—impels us to charity for our brothers and sisters, especially the most vulnerable.

In this article, I want to reflect with you on two of the Beatitudes, allowing the witness and words of St. Francis of Assisi to help us understand how our inner life is transformed by the reception of Holy Communion. Flowing from that transformation, as “other Christs,” we are fortified to live lives of charity in action.