The Holy Samaritan Woman: Inspiration for the Spiritual Life of Catechists

Once on a hot summer day in France, I hiked a winding path with some companions all the way to the very source of a small stream. Having grown hot and tired from our hike, our local guides instructed us to rest a few moments and refresh ourselves at the spring. I hesitated as I watched the others drink confidently, even eagerly. The closest I had ever come to drinking untreated water was in sipping from the garden hose!

Their beckoning won me over, however, and I joined them. We drank the cold flowing water made all the more delicious by our thirst and the natural stone spicket. It occurred to me then that God intended water to be like that—pure, refreshing, a free gift of his goodness.

In the Gospel of John, Jesus promises that “living water” will well up in those who believe. The scene of Jesus and the Samaritan woman in John 4:1–42 is one those passages. This scene is particularly valuable for those who evangelize and catechize because it offers us a model of an authentic encounter with Jesus Christ and reveals to us the effects of that living water he promises.

In fact, we could almost name “the holy Samaritan”—as St. Teresa of Ávila calls her—our patron saint. We want to drink of the water Christ offers and teach others how to do the same, just as she did that day in Samaria.

Important Announcement for Today's Catholic Teacher Readers

Important Announcement Regarding the Future of Today’s Catholic Teacher Magazine

Dear Today’s Catholic Teacher Reader,

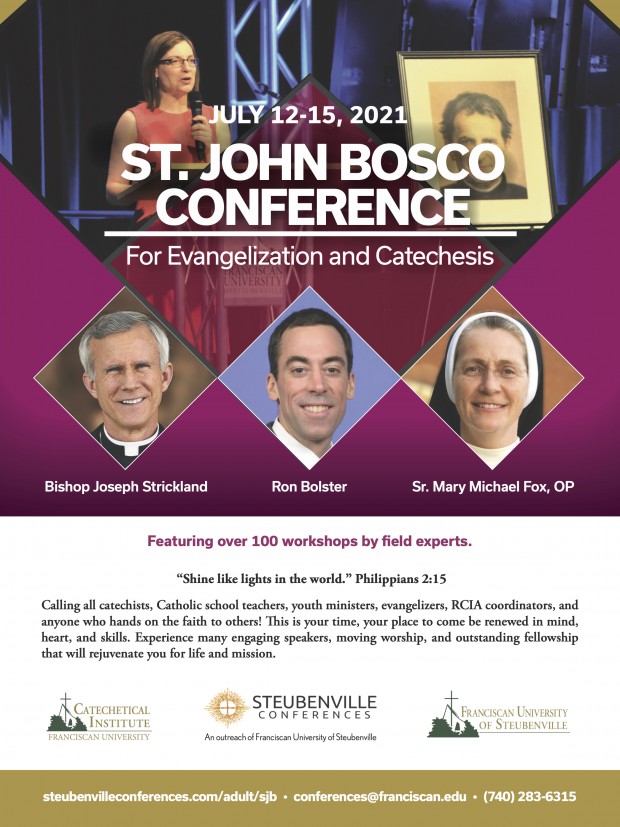

AD: Summer Conference for Catechists and Catholic School Teachers

Click here to learn more about this enriching conference with a wide array of speakers and topics.

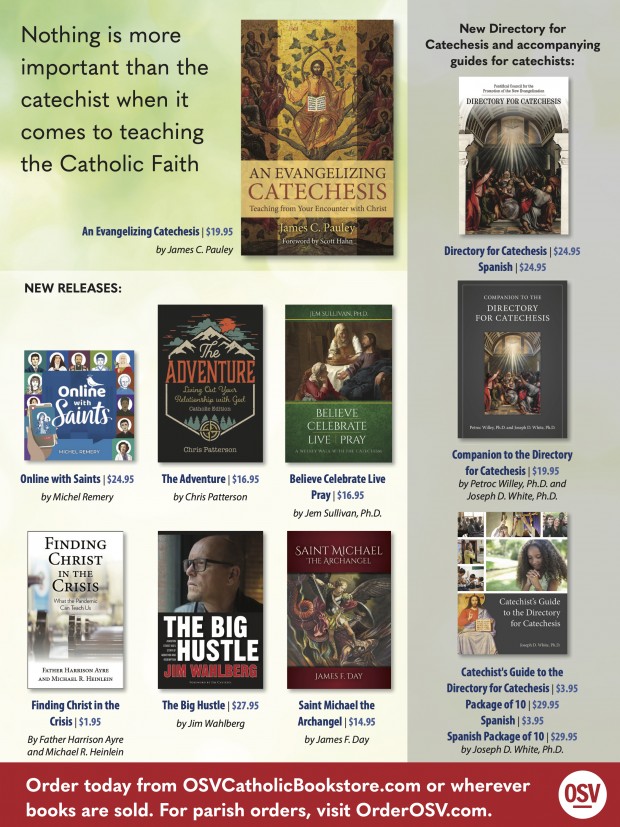

AD: Study Guides, Online Saints and more from OSV!

Order today from OSVCatholicBookstore.com or wherever books are sold. For parish orders, visit OrderOSV.com.

This is a paid advertisement in the January-March 2021 issue. Advertisements should not be viewed as endorsements from the publisher.

Inculturation and Organizational Structures in the Directory for Catechesis

This article explores chapters 10-11 of the Directory for Catechesis.

Catechesis at the Service of the Inculturation of the Faith

At the press conference to present the new Directory for Catechesis (2020), Archbishop Rino Fisichella, president of the Pontifical Council for the Promotion of the New Evangelization, stated, “The need for a new directory was born of the process of inculturation which characterizes catechesis in a particular way and which, especially today, demands a special focus.”[1] The preface sets forth the reasons for producing a third catechetical directory for the universal Church at this particular time, namely the publication of Pope Francis’ Apostolic Exhortation Evangelii Gaudium and the dual phenomena of the digital culture and the globalization of culture (see DC, Preface, p. 4). Given this context, then, it is not surprising that the Directory for Catechesis devotes two chapters to the interaction of catechesis and culture.

Chapter eleven is titled “Catechesis at the Service of the Inculturation of the Faith.” After a brief but important introductory paragraph, the chapter contains two sections: “Nature and Goal of Inculturation of the Faith,” and “Local Catechisms.”

The introductory paragraph retrieves a description of the process of inculturation from St. Paul VI’s Apostolic Exhortation Evangelii Nuntiandi. There immediately follows a parallel citation from Pope Francis’ Evangelii Gaudium. These two perspectives on the process of the inculturation of the faith set the context for the chapter’s exploration of the dynamic interaction of faith and culture.

On the one hand, Evangelii Nuntiandi insists on the inculturation of the Gospel message “without the slightest betrayal of its essential truth.”[2] And on the other, Evangelii Gaudium highlights the “new and eloquent expressions” of the Gospel message that are generated in the process of inculturation.[3] The former emphasizes that which is given: the unchanging truth of the Gospel message in every age. The latter emphasizes that which is received: the Gospel message accommodated to the particular circumstances of a culture.

Catechetical Methodology and its Application to the Lives of Human Beings

This article explores chapters 7-8 of the Directory for Catechesis.

Introduction and Context

It is now twenty-three years since I eagerly read the last General Directory for Catechesis and made efforts to implement its teachings within the catechetical programs in some of the Catholic schools in Australia. Much has changed in our world since 1997, and the new Directory for Catechesis has achieved an outstanding synthesis of what was sound and helpful in the earlier document, while taking us forward with new and profound insights for today. In this article, l will be addressing the essential contents of chapters seven and eight of the Directory, namely: “Methodology in Catechesis” and “Catechesis in the Lives of Persons.” Before doing so, however, I would like to frame my comments within the context of the Directory as a whole. Firstly, it is essential to understand that catechesis must now take place in a world overwhelmingly influenced by globalization and the digital culture. According to the Directory, there are advantages and disadvantages associated with both phenomena. The danger associated with globalization is the tendency towards international standardization, which puts pressure on local cultures. With regard to digital culture, there is an implicit tendency towards a “one size fits all” approach implicit in digital culture, which undermines an essential anthropological truth.[1] We must always keep in mind that every person is unique and unrepeatable.

It seems to me that there are three essential insights running through the document which could perhaps be summed up in three words: accompaniment, kerygma, and mystagogy. All of these themes appear multiple times in the document.

The emphasis on kerygma takes up a focus that began to appear strongly in Evangelii Gaudium, which had already taught that “all Christian formation consists of entering more deeply into the kerygma.”[2] It was also in this 2013 document that we were given a simple definition: “Jesus Christ loves you; he gave his life to save you; and now he is living at your side every day to enlighten, strengthen and free you.”[3] The Directory is insistent that in the initial stages of evangelization the primary focus should be on making present and announcing Jesus Christ. Moreover, at every step of the way, there can be no true evangelization if the name and teaching of Jesus Christ, the Son of God” are not proclaimed.[4]

Mystagogy, the Directory reminds us, is a liturgical catechesis highlighting the way in which the liturgy makes present the mysteries revealed in the Scriptures. It introduces us to the living experience of the Christian community, the true setting of the life of faith. It is a progressive and dynamic process, rich in signs and expressions and beneficial for the integration of every dimension of the person (DC 2). The emphasis on mystagogy has been regarded as foundational for catechesis since the publication of the Apostolic exhortation Sacramentum Caritatis in 2007.

Finally, those familiar with the work of Pope Francis will not be surprised with the highlighting of accompaniment. This notion occurs in the Directory more than any other. It acknowledges the pastoral difficulties being experienced at this time by so many in our world. We are asked to emphasize the mercy and love of God, who seeks out the lost and the lonely in our world.

Methodology in Catechesis

I have now spent more than thirty years thinking about issues of catechetical methodology, making this a significant component of my doctoral, post-doctoral, and practical work. I wish to affirm that in this chapter the Directory has drawn together all of the best practices of which I am currently aware in this field. The document soundly affirms that there can be no single method in catechesis—one size certainly does not fit all. What is more, it is made clear that catechesis is an event of grace, brought about by the word of God within the experience of the person. At the same time, it is grounded in an authentic Christian anthropology and guided by the demands of the Gospel (see DC 195). The example of the teaching of Jesus in the parables is offered as the best example of catechesis in action. In the parables, the same concrete and human image is offered to everyone, but the meaning is left to unfold in accordance with the work of the Holy Spirit in each person in their own time.

Educating in the Lord’s Ways

This article explores chapters 5-6 of the Directory for Catechesis.

When we have reached chapters five and six in the Directory we would be forgiven for being tempted to jump nimbly over these two chapters into the details of methodological considerations so amply provided in chapter seven and the focus on different groups to whom we minister in chapter eight. We have already received the Directory’s account of catechetical goals, both ultimate and proximate; we have benefitted from a rich account of the person of the catechist and of the catechist’s formation needs. We know the tasks of catechesis and where to draw from the wells of the Church’s sources for our ministry needs. We have already examined questions of structure and been guided to understand how to use the catechumenal model as a paradigm for all catechesis. The necessary kerygmatic nature of catechesis has been developed at length for us. In short, we are ready to examine questions of application and the practical out-workings for how to fit all of this into our ministerial contexts.

The two chapters we now face stand at the entrance to the discussion of methodology and might seem to us a rather unwieldy and unnecessarily lengthy introduction to that subject. We are in a new part of the Directory, “The Process of Catechesis,” which seems to speak to the level of immediate practicalities, and yet the tone is theological and the themes appear to be picking up those of the opening chapter on the content of Revelation. What function do these two chapters perform within the whole? Are we facing simply a kind of reflective interlude, or is there something more substantial for the work of catechesis being offered here?

Understanding the Process of Catechesis

The best way to approach these chapters is, in the first place, to keep in mind the broader heading of the part within which they are found: “The Process of Catechesis.” These chapters, together with chapter seven on catechetical methodology, describe the process by which all authentic catechesis takes place. They tell us, in other words, what is taking place in catechesis. That “is” contains a hidden “ought,” of course: they describe what takes place in all catechesis that is undertaken according to the mind and heart of the Church.

The second point of importance is to read these two chapters together, as a pair. Chapter five explains what it calls “the pedagogy of the faith” and chapter six illustrates what this pedagogy looks like and provides us with an exemplar in the form of the Catechism of the Catholic Church. In what follows, then, we will treat the two chapters together, unfolding the meaning of the pedagogy of the faith and then seeing how it is manifested for us and made clear in the Catechism. There are three elements in the “process of catechesis” to which the Directory alerts us.

From the Shepherds: Our Personal Vocation

A fund amental theme that runs throughout Sacred Scripture is to be called by name. In other words, in the eyes of God, you and I are not simply one in a crowd, nor are we a serialized number.

amental theme that runs throughout Sacred Scripture is to be called by name. In other words, in the eyes of God, you and I are not simply one in a crowd, nor are we a serialized number.

Becoming Windows for the Light of the Living God

This article explores chapters 3-4 of the Directory for Catechesis.

One could liken chapters three (The Catechist) and four (The Formation of Catechists) of the new Directory for Catechesis to a meditation on windows and how they are made.

Identity and Vocation of the Catechist

In the early Church, those who followed the Way were often called “saints.” This designation did not refer to the canonized (or even “canonizable”), but to the fact that, as Joseph Ratzinger points out, all of the faithful were called “to use their experience of the risen Lord to become a point of reference for others that could bring them into contact with Jesus’ vision of the living God.” Ratzinger applies the image to the present, saying that believers should, “in all their weaknesses and difficulties, be windows for the light of the living God.”[1]

Like a window, which offers a particular glimpse of light outside, the catechist facilitates a unique encounter with his or her own source of light. The catechist is a reference point, a witness to the Tradition of the Church and “a mediator who facilitates the incorporation of new disciples of Christ into his ecclesial body” (DC 112).

This means, of course, that the catechist participates in a mission that he or she did not initiate. As the Directory says, the catechist is “a facilitator of an experience of faith of which he is not in charge” (DC 148). Instead, the catechist is empowered by the Holy Spirit, “the true protagonist of all authentic catechesis,” and participates in Jesus’ mission “of introducing disciples into his filial relationship with the Father” (DC 112). Catechesis is, above all, what Benedict XVI calls a theandric activity. This is to say it is “made by God, but with our involvement and implying our being, all our activity.”[2] The True Catechist—and this is a critical point—is Jesus Christ. The window itself is not the source of light, but that which mediates the entry of the light into the room. Similarly, the human catechist participates in the mission of the light by mediating its presence today. The catechist fosters an encounter with Jesus Christ, the One who initiates this encounter.

According to paragraph 113 of the Directory, the catechist is:

- A witness of faith and a sign for others of the credibility of Christianity through the testimony of his or her life. The catechist also serves as a keeper of the memory of God who safeguards the “memory of God’s history with humanity.”

- One who “introduces others to the mystery of God, revealed in the paschal mystery of Christ” by acting as both a teacher and a mystagogue. As a teacher, the catechist transmits the content of the faith. As a mystagogue, the catechist leads others in the mystery of faith by “introducing them to the various dimensions of Christian life.”

- An educator who is “an expert in humanity” and skilled in the art of accompaniment.[3]

In the early Church, every Christian was to be a saint. That call remains, and it aligns with the catechetical call for all of the faithful. Through Baptism and Confirmation, the Directory says, "Christians are incorporated into Christ and participate in his office as priest, prophet, and king; they are witnesses to the Gospel, proclaiming it by word and example of Christian life” (DC 110). In this way, “the whole Christian community is responsible for the ministry of catechesis” (DC 111). We might think of it as something of a universal call to catechesis—a call for all the baptized to witness and to proclaim, a call for “the transmission of faith and for the task of initiating" (DC 112).

Catechists in the Body of Christ

While windows have something of a “universal call,” namely, the mediation of light, it is not the case that one window is exactly the same as the next. Windows vary based upon their function for a space, though their fundamental purpose is the same. Vatican II’s dogmatic constitution Lumen Gentium emphasizes the universal call to holiness for all the faithful, regardless of rank or status, while making the point that the response to the call takes on a certain uniqueness based upon one’s state in life.[4] While all the faithful are called to catechize, the Directory specifies precisely how that call is to be answered according to one’s “particular condition in the Church: ordained ministers, consecrated persons, lay faithful” (DC 111). These distinctions of catechetical roles allow for a rich flood of the light of Christ in the Church and the world.

An Invitation to a Faithful, Dynamic Renewal of Catechesis

This article explores chapters 1-2 of the new