Giving Our Hearts to Jesus

One day about 6 years ago, when I worked as a Director of Religious Education for a rural Catholic parish, I was in my office browsing Facebook. I saw an image of a Catholic evangelist on a boardwalk out in public evangelizing a man wearing a Darth Vader helmet and riding a unicycle. Of course, I had to click through the link to read the story about St. Paul Street Evangelization. I contacted the ministry and started a team at my parish. I admit that I didn’t actually expect that direct evangelization would be fruitful, at least I didn’t expect that a 2-minute conversation with someone that I never met could lead to a genuine conversion to Jesus Christ and his Church. I thought most of our work would just be arguing about doctrine and planting seeds. After all, wasn’t everyone walking down the street wondering whether Catholics worship Mary?

Therefore, I didn’t know how to react when, the second time I went out to evangelize in our community, we met a man, Tom, who had just read the Catechism of the Catholic Church and wanted to know more about Jesus. He didn’t know any Catholics and was too afraid to walk into a random Catholic Church. I was floored that after we explained the Gospel, his heart was “burning within him” and he wanted to know what to do next.

How were we going to help him at that moment to satisfy his need for Jesus in his life? I knew my priest wouldn’t be pleased if my team baptized him right then and there. Telling him that he should just “go to a program” wasn’t a satisfactory answer. A program a few weeks distant would not address his need for a relationship with the Savior who loves him right now.

In Pope Emeritus Benedict XVI’s 2011 address to the bishops of the Philippines, he states that “your great task in evangelization is therefore to propose a personal relationship with Christ as key to complete fulfillment.” That moment on the street may not have been the right moment to baptize Tom, but it was the perfect time to introduce him to Jesus. We prayed together to thank God for Tom’s life, repent of our sins, and ask Christ to come into Tom’s heart, to give him all of the graces God had for him. We led him to Jesus.

Catholic Education—A Road Map: The World’s Most Frequently Cited Educationalist, John Hattie

In previous articles for this series, I have confined myself to authors who have written from a Catholic perspective. While it may be true that some contemporary educational practices are seriously at odds with the teaching of the Church, one should avoid the temptation to be dismissive of all contemporary educational theories. The General Directory for Catechesis makes it clear that the Church “assumes those methods not contrary to the Gospel and places them at its service… Catechetical methodology has the simple objective of education in the faith. It avails of the pedagogical sciences and of communication, as applied to catechesis…”[1] Indeed, there are some excellent contemporary practices that are entirely compatible with a Catholic vision of education. In this article, I will attempt to provide a brief introduction to the work of Professor John Hattie, currently the most “cited” educational theorist in the world. Hattie does not claim any Christian credentials; his claim is that he relies entirely on data and evidence. For this reason, John Hattie is widely unpopular in his own profession due to his refusal to support educational practices that are obviously failures. Among his key works are Visible Learning (2010), Visible Learning for Teachers (2011) and Visible Learning Feedback (2018). In these texts, Hattie examines many different educational practices and assigns them a score for their effectiveness. Many of the educational “fads” of the past fifty years, despite their popularity in schools, have received very low scores from him. It will not be possible in an article of this length to offer anything more than touch on Hattie’s findings, so I encourage readers to do their own research and investigate some of his many articles available online. They have interesting and valuable contributions to make to the science of pedagogy.

What I will offer in the remainder of this article is a very brief description of eight highly effective teaching practices identified by Hattie in Visible Learning, together with effect size scores. These are calculated using standard statistical measures which need not concern us here. An “effect size” of 0.4 is what should be expected from any sound teaching practice. It means that a student has improved at an average rate over a one year period. If the rating were to be 0.8, it means that the student has made double the amount of progress, equivalent to completing two years of learning in one year. Hattie works not only by conducting his own research, but also by cross checking his findings with multiple pieces of other research: a technique known as “meta-study.”

Restored Order Confirmation: Implementation in the Archdiocese of Denver

On May 29, 2012, it was announced that Bishop Samuel Aquila of Fargo, North Dakota was returning to his home diocese of Denver to become its fifth archbishop. Many archdiocesan leaders had an immediate hunch: Restored Order Confirmation was coming to the archdiocese. Bishop Aquila had already restored the order of the sacraments of initiation in Fargo, and even received public praise for it from Pope Benedict XVI during an ad limina visit to Rome. These expectations proved true when in the fall of 2013 the archdiocese began internal preparations to move toward Restored Order Confirmation, becoming the first archdiocese in the United States to do so. By 2020 the process of transition will be complete, though a majority of parishes in the archdiocese have already begun celebrating the Sacraments of Confirmation and First Communion together in the third grade. To assist this move toward restoring the sacraments to the traditional order of Baptism, Confirmation, and First Communion, the Office of Evangelization and Family Life Ministries (EFLM) conducted workshops and created a number of resources. This article will reflect on the process used by the Archdiocese of Denver in this reordering and the impact it has had upon catechesis within its parishes.

Inspired Through Art: After First Communion by Carl Frithjof Smith, 1892

Norwegian painter, Carl Frithjof Smith, is not a well-known artist today. Despite his lack of fame, his art is beautiful and worthy of recognition and study. Smith lived and worked for all of his adult life in Germany, until his death in 1917. After studying at the then thriving Academy of Fine Art in Munich, Smith took a teaching position in Weimer, Germany, where he remained for most of his life. His work consists mainly of portraits and genre paintings.

Genre painting explores the sphere of a person’s ordinary activity. Focusing on scenes from daily life, these works delve into human interactions, often enticing us to examine our own everyday moments in a more thoughtful manner. The genre painter must be someone in touch with the inner psyche of others. In what is perhaps his most famous work, After First Communion, Smith triumphs at this craft, presenting a scene that is rich in human feeling and meaning.

In the painting we see Mass participants spilling out of a church door on the left, down steps, and onto the street. This crowd consists mainly of young girls. What is most striking about this painting is the dazzling white of the girls’ ceremonial dresses. Worn at baptism, first Eucharist, and marriage, white garments symbolize the purified soul of the believer. The gray stone of the church contrasts with the vibrant white of the girls’ garments. There is an ethereal feel to the work that is anchored by the darker tones of the church and the garments of fellow parishioners. Smith balances the careful study of figures with a soft atmospheric treatment of the subject matter. This interplay is particularly clear in his treatment of the background compared to the foreground. The subject matter is clear and well described, and the use of contrast is greater in the foreground, while soft colors and brushstrokes are used in the background. His art is considered to be a middle way between rigid academism and airy plein air painting. While the general feel of the painting is lovely and pleasant, the expressions and interactions of the subjects are what draw us deeper into the work.

Como ayudar a los niños y a sus familias a vivir los Sacramentos de la Penitencia y Reconciliación y de la Eucaristía

Children's Catechesis: Helping Children & Families Live the Sacraments of Penance & Eucharist

The Catechism of the Catholic Church calls the sacraments, “the masterworks of God in the new and everlasting covenant” (1116). The sacraments confer upon us a special grace that assists us in becoming the people God created us to be. Unfortunately, too often the first celebration of the sacraments in childhood is approached as if it were a one-time developmental milestone, rather than the beginning of a lifelong celebration or a further step down the path of continuing conversion.

Both experience and research have shown us that the period of preparation for the Sacraments of Penance and Eucharist is a rare time when even families who are only marginally connected to the parish are willing to spend more time in formation. This can be an opportunity for evangelization, if catechists and catechetical leaders are open to the Holy Spirit and focus their catechesis not only on preparation for the initial reception of the sacraments but also on the ways in which the sacraments can change our lives.

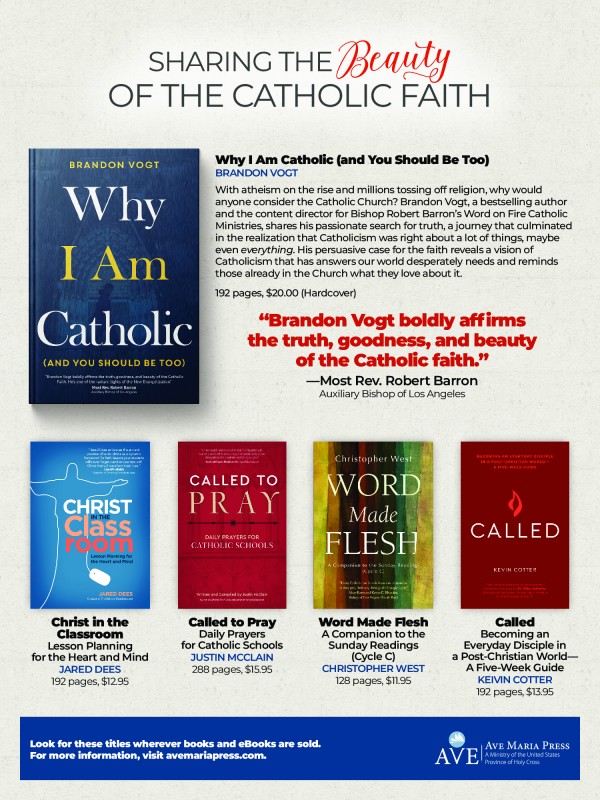

AD: Ave Maria Press—Sharing the Beauty of the Catholic Faith

This is a paid advertisment. For more from Ave Maria Press click here or call (800) 282-1865, ext. 1.

Catholic Education—A Road Map: The Work of Sofia Cavalletti, Catechesis of the Good Shepherd

Sofia Cavalletti was arguably the most effective catechetical theorist and practitioner of her era. Born in 1917, she belonged to a noble Roman family, who had served in the papal government. Marchese Francesco Cavalletti had been the last senator for Rome in the papal government, prior to its takeover in 1870 by the Italian state. Sofia herself bore the hereditary title of Marchesa, and lived in her family's ancestral home in the Via Degli Orsini. In 1946, the young Sofia Cavalletti began her studies as a Scripture scholar at La Sapienza University with specializations in the Hebrew and Syriac languages. Her instructor was Eugenio Zolli, who had been the chief rabbi of Rome, prior to and during World War II and who had become a Catholic after the war. Following her graduation, Cavalletti remained a professional academic for the whole of her professional career.

Cavalletti's involvement with catechetics came about by chance, in 1952, after she was asked to prepare a child for his first communion. Soon after this experience, Cavalletti began collaborating with Gianna Gobbi, a professor of Montessori education. Together, they developed what came to be known as the Catechesis of the Good Shepherd, painstakingly creating materials that would serve the religious needs of children from the ages of three to twelve years. Taking the Montessori sensitive periods as a starting point and guided by the response of real children as the “reality check,” Cavalletti refined her understanding of the religious experiences that children were likely to respond to at each stage of their development. She would create materials and make them available to the children. If the material was not used, she determined that it had not met the mark and she would dispose of it, irrespective of how much effort she had put into it.

Very early in her work, Cavalletti discerned the central role of “wonder” in a child’s religious development and she realized that for young children (and indeed for every human being), wonder is evoked by “an attentive gaze at reality.”[i] Consequently, young children were encouraged to begin their relationship with God by recognizing, one by one, the gifts offered to them in the created world. To meet this need, the Montessori “practical life” works were found to be ideal. Children were given tasks such as flower arranging, slow dusting, leaf washing and the like. The experience of Montessori classrooms for over a hundred years has born witness to the effectiveness of this approach. Engagement with concrete “hands on” activities seem to be the basis not only of religious development but for learning of any kind.

The careful observation of the needs of real children by Montessori had identified the basic stages of learning, (outlined in my previous article). Cavalletti summed this up in a simple axiom: first the body, then the heart, then the mind. As the twentieth century progressed, she evaluated new ideas in education, Biblical scholarship, and theology. Cavalletti did not easily fall prey to a widely reported educational phenomenon, the “band wagon effect.” She was an “action researcher” who allowed herself to be guided by the reactions of the children she was working with. If a learning material failed to engage the children, it was discarded and alternatives sought.

One of the most striking and commonly reported phenomena of the Catechesis of the Good Shepherd is that children seem to be able to arrive at profound theological understandings for themselves—without being told.

Catequesis para Niños: La formación de una cultura de oración en el hogar

¿Qué recuerdas de tu primer día de clases del primer grado de la escuela primaria? ¡Mi recuerdo ha dado a mi vida una finalidad profética y un valor que perdurará toda la vida! Tras pasar lista y asignar sus lugares a sus 120 alumnos (¡no es ningún error tipográfico esto!), la menuda Sr. Santa Rosa nos avisó que nuestra primera lección sería la más importante de nuestra vida. Repartió nuestro primer libro de catecismo y nos indicó que lo abriéramos en la primera lección. Con lápiz en mano, encerramos con un círculo las preguntas número uno, dos, y tres. La Hermana nos instruyó sobre el sentido de las palabras y nos dijo que les pidiéramos a nuestros papás que nos enseñaran cómo decir las palabras con los ojos cerrados.

Mi mamá vigilaba la hora de las tareas. Me asombró cuando, sin mirar el libro, conocía las respuestas a las tres preguntas. Más asombrosa aún fue la plática durante la cena esa noche. Mi mamá dijo, “Pat, dile a tu papá qué aprendiste en la escuela hoy”. Le miré derechito a los ojos de mi papá y declaré con convicción, “Aprendí porqué Dios me creó”. Sin titubear en absoluto, mi papá proclamó, “Pat, Dios te creó para conocerlo, amarlo, y servirlo en este mundo, y para que seas feliz con Él para siempre en el próximo”. La respuesta que me dio mi padre tuvo una influencia exponencial porque, con justa razón, se había ganado el apodo de “Daddy Old Bad Boy” (Papá Viejo Niño Travieso). Su mal comportamiento era legendario y por eso todos los años los Reyes Magos le dejaban carbón en su bota navideña. Entonces, cuando este hombre sabía por qué Dios me había creado, ¡me tragué el anzuelo y abracé totalmente esta creencia! Haciendo eco del sentimiento de Robert Frost, “eso ha hecho toda la diferencia.” [i]

El llegar a conocer a Dios – y crecer en ese conocimiento y la experiencia del mismo a lo largo del tiempo – es nuestro llamado universal, nuestra vocación primaria. El conocimiento de Dios conduce al amor. ¡Una persona que no ama a Dios es una persona que no conoce a Dios! Y nosotros mismos - cuando amamos a una persona, no podemos menos que desbordar en el servicio que le damos por amor.

La oración: tanto acción como actitud

Como “Primeros Mensajeros del Evangelio”[ii] los padres de familia tienen el privilegio y la responsabilidad de presentarles Dios a sus hijos; de sensibilizarles a que reconozcan los caminos de Dios; de aprender a hablar con Dios; y de responderle a Dios de manera apropiada según su edad. La oración es el hilo conductor para todos estos objetivos.

¿Qué es la oración? Las definiciones abundan. Hasta Wikipedia interviene sobre el tema. Mi definición nuclear, y es la que ofrezco a los padres de familia actuales, proviene de ese mismo catecismo de primer grado: “La oración es elevar nuestra mente y nuestro corazón a Dios”. La oración puede ser vocal o mental, formal o informal, privada o colectiva, programada o espontánea. La oración cambia con la edad y las etapas de la vida, así como la calidad y el estilo de comunicación cambia con el tiempo entre personas quienes estén creciendo en su relación.

La oración es comunicación con Aquél que nos conoce mucho mejor que nosotros mismos nos conocemos, y que nos ama más allá de nuestra capacidad para comprender tal amor. Sin tregua y sistemáticamente Dios nos comunica su amor y su voluntad que da vida, aunque a menudo no nos demos cuenta y estemos inatentos. Frecuentemente, el ajetreo de la vida bloquea nuestro reconocimiento de los movimientos de Dios. Los ruidos de nuestro ambiente ahogan los susurros del amor de Dios. Independientemente de nuestra percepción, Dios sigue hablando, tendiéndonos la mano, y ofreciendo su amistad.

La oración es acción y actitud. Toda persona, lugar, estímulo, o evento que eleva nuestra mente y nuestro corazón a Dios puede ser catalizador para la oración. Las prácticas espirituales comprendidas y adoptadas voluntariamente con fidelidad elevan nuestra conciencia espiritual. Los ambientes, costumbres y ritos que tutoran al alma o recuerdan la presencia de Dios pueden incitar un santo deseo y afecto.

Children's Catechesis: Forming a Culture of Prayer within the Home

What do you remember of your first day of Grade One? My memory gave prophetic purpose and life-long value to my life! After taking roll and assigning seats to her 120 students (not a typographical error!), petite Sister St. Rose announced that our first lesson would be the most important lesson of our lives. She distributed our first catechism book and directed us to lesson one. With pencil in hand, we circled question numbers one, two, and three. Sister instructed us in the meaning of the words and told us to have our parents teach us how to say the words with our eyes closed. My mother proctored homework time. She amazed me when, without looking at the book, she knew the answers to the three questions. More amazing yet was dinner conversation that night. Mom said, “Pat, tell dad what you learned at school today.” I looked my dad straight in the eye and declared with conviction, “I learned why God made me.” Without skipping a beat my father proclaimed, “Pat, God made you to know him, to love him, and to serve him in this world, and to be happy with him forever in the next.” Dad’s reply had an exponential influence because he had justly earned the nickname of “Daddy Old Bad Boy.” Dad’s misbehaviors were legendary and yearly Santa Claus deposited coal in his stocking because of it. So, when this man knew why God made me, I embraced the belief hook, line, and sinker! Echoing the sentiment of Robert Frost1, “that has made all the difference.” Coming to know God—and growing in that knowledge and experience over time—is our universal call, our primary vocation. Knowledge of God and the ways of God leads to love. A person who does not love God does not know God! And whenever any of us love another person we can’t help but overflow into service for them. Prayer: Both Action and Attitude As “First Heralds of the Gospel”2 parents bear the privilege and the responsibility to introduce their children to God; to sensitize them to recognize the ways of God; to learn how to speak to God; to distinguish God’s voice and will from other voices; and to respond to God in age-appropriate ways. Prayer is the common thread for these goals. What is prayer? Definitions abound. Even Wikipedia weighs in on the topic. My core definition, and one that I offer to contemporary parents, comes from that same first grade catechism: “Prayer is the lifting of our minds and hearts to God.” Prayer can be vocal or mental, formal or informal, private or corporate, scheduled or spontaneous. Prayer changes through the ages and stages of one’s life, just as the quality and style of communication changes over time between persons who are growing in relationship. Prayer is communication with the One who knows us better than we know ourselves and Who loves us beyond our ability to comprehend such love. Consistently God communicates God’s love and life-giving will, though we are frequently unaware or inattentive. Often the busyness of life blocks recognition of God’s movements. The noises of our environment drown out the whispers of God’s love. Regardless of our awareness, God continues to speak, to reach out, and to offer friendship. Prayer is both an action and an attitude. Any person, place, stimulus, or event that lifts our minds and hearts to God can be a catalyst of prayer. Spiritual practices that are understood and faithfully embraced raise our spiritual consciousness. Environments, customs, and rituals that tutor the soul or recall God’s presence can stir holy desire and affection.