The Real Presence of Christ in the Eucharist should be numbered among the most kerygmatic of the Church’s doctrines. Here is where the Son of God, who out of the immensity of his divine love became incarnate, has chosen to dwell amongst his people until the end of time. Here is where divine charity makes itself available to the human heart. Here is where one finds the deepest communion this side of heaven in which to rest. In a time in which the bishops of the United States seek to enkindle a renewed encounter with Jesus Christ in the Holy Eucharist, the reality of the Lord’s presence in the Blessed Sacrament should be proclaimed by catechists everywhere so that the eyes of many can be opened and that Jesus might be made known to them in the breaking of the bread (Lk 24:31, 35). I offer this article as a supporting addition to the wealth of insight the U.S. bishops have offered in their document The Mystery of the Eucharist in the Life of the Church, which is to say, as a meditation to aid catechists in their unpacking of it, especially its section on the Real Presence of Christ.[1] In the following, my goal is to deepen our understanding of the Real Presence precisely so that catechists can better foster encounters with the Lord in the Blessed Sacrament as it is celebrated both within and outside of Mass.

The Real Presence of Christ in the Eucharist should be numbered among the most kerygmatic of the Church’s doctrines. Here is where the Son of God, who out of the immensity of his divine love became incarnate, has chosen to dwell amongst his people until the end of time. Here is where divine charity makes itself available to the human heart. Here is where one finds the deepest communion this side of heaven in which to rest. In a time in which the bishops of the United States seek to enkindle a renewed encounter with Jesus Christ in the Holy Eucharist, the reality of the Lord’s presence in the Blessed Sacrament should be proclaimed by catechists everywhere so that the eyes of many can be opened and that Jesus might be made known to them in the breaking of the bread (Lk 24:31, 35). I offer this article as a supporting addition to the wealth of insight the U.S. bishops have offered in their document The Mystery of the Eucharist in the Life of the Church, which is to say, as a meditation to aid catechists in their unpacking of it, especially its section on the Real Presence of Christ.[1] In the following, my goal is to deepen our understanding of the Real Presence precisely so that catechists can better foster encounters with the Lord in the Blessed Sacrament as it is celebrated both within and outside of Mass.

The Doctrine of Transubstantiation

The doctrine of transubstantiation takes its most noteworthy form from the teaching of St. Thomas Aquinas, though the term was in use by Christians before him.[2] The Catechism of the Catholic Church uses the term in paragraph 1376 in its teaching on the Real Presence. Theology both before and after the Second Vatican Council has sometimes squabbled over the appropriateness of the technical word, some finding the Aristotelian roots of it too outdated or too challenging for most Catholics, but the Catechism follows the Council of Trent by stating that the term is “fitting” and “proper,” indicating a preferential option for the language while not necessarily demanding it.

In truth, Aquinas’ teaching, while dependent on the philosophy of Aristotle, is not so difficult to understand. One way in which Aristotle described reality was by way of “substances” and “accidents.” By substance, he meant the underlying or deepest reality of a being, such that, were one to change that reality, it would be a different being. By accident, he meant the changeable qualities of a given being, properties that are therefore secondary to it. One could, for instance, think of the development of a human from a baby to an adult. The accidents of a person change as one grows in age—eye color often makes subtle changes, height and weight change, as do the quality of one’s skin, voice, and musculature. And yet, when we consider the person as a baby and as an adult, we recognize that an inner reality is still the same. It is still the same human being because the substance has remained. Aristotle’s terms are, thus, simply a way of describing what we already know by common sense.

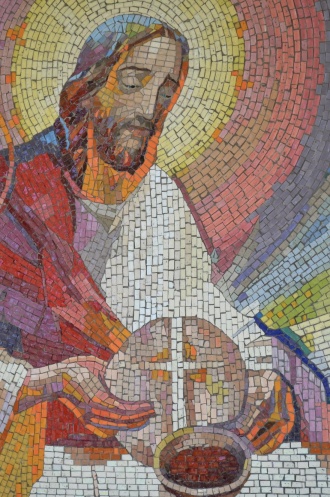

Even so, if we were to stop at this explanation of the doctrine, we might miss St. Thomas’ point in expounding it. The Angelic Doctor harnesses this way of describing reality to help us understand the awesome mystery of the Real Presence. When a priest raises the bread and chalice and says the words of institution, the accidents of bread and wine remain, but the inner reality has changed. There is a change (trans) of substance (substantia). Jesus, the High Priest, has spoken his creative word through his minister and, by the power of the Spirit, has taken our offerings and turned them into himself. In doing so, he has humbled himself, taking the form of common food so that we might literally take him into ourselves and commune with him. The words of St. Thomas’ hymn, written for the Solemnity of Corpus Christi, capture the heart of this teaching on the Real Presence: “Godhead here in hiding, whom I do adore / Masked by these bare shadows, shape and nothing more, / See, Lord, at thy service low lies here a heart / Lost, all lost in wonder at the God thou art.”[3]

With this teaching in view, we now turn to its source in Sacred Scripture.

The Real Presence in the Old Testament

Modern readers of the Old Testament should not overlook what is novel in the religious history of humankind. Men and women have nearly universally called upon, groped for, and sought to appease the divine. But, with the election of the Israelites, the divine has done something incomparably new: God has drawn close to us. The movement comes from “his side,” so to speak.

The staggering presence of God is the centerpiece of the Old Testament story. We see this as early as the call of Moses, who on Mount Horeb discovers the divine presence in a burning bush which is not consumed, receives the mysterious divine name “I Am,” and hears his vocation to free God’s people for worship of the one, true God. The moment compels him to remove the sandals from his feet. God is the transcendent foundation of all existence, is existence itself, yet here he has entered time and space. He has revealed himself as the God of presence, “God with us,” the God who will be with his people.

The Lord once again makes himself known when the Israelites, freed by the sacrifice of the Passover lamb, begin the journey out of Egypt and from slavery to freedom. The Lord leads the way under the figure of a pillar of fire and cloud. His personal presence is one of light and mystery; it is one of protection.

Upon returning to Horeb, also called Sinai, Moses ascends and once again encounters the living God, this time with an entire people awaiting him at the foot of the mountain. In receiving the Law, he is exposed to God’s radiating presence, and after coming down the incline, he sets up a tent outside the camp where he and the Lord can continue to converse. After speaking so intimately with the great I Am, his face radiates such that he must veil it from his fellow Israelites, a sign of the potential transformation that awaits those who are regularly exposed to the divine presence. Moses’ vocation is to lead the people of God to the promised land. Yet, before setting out from the mountain, two separate times he movingly makes a request of the Lord: “If you are not going yourself, do not make us go up from here” (Ex 33:15; see also 34:9). For one who has experienced God so intimately, there is no freedom apart from this presence and no promised land unless he dwells there, too.

God mercifully answers Moses’ request in having the Israelites construct a tabernacle, a portable dwelling place that will house the Ark of the Covenant, upon which God will speak with his people from the lid of the Ark, known as the mercy seat. This tented dwelling allows the Israelites to carry the Lord with them throughout their journey. Exodus tells us that God’s presence dwelled there as a cloud by day and fire by night. When the cloud remained, the Israelites rested. When it lifted, the Israelites continued on their way (Ex 40:36–38).

Though God was mercifully present to his people, his people were not always “present” to him. In the desert, they complained against him, forgot the miracles he had wrought, and even rejected the promise of a land to call their own. Despite this, the Lord continued to personally intervene for their welfare, adding to the miraculous manna he had given to sustain them meat and water as well as salvation from various ailments.

Upon their arrival at the promised land, he helped establish a Davidic royal “house,” or dynasty, to govern the Israelites’ affairs, and, in return, Solomon built a “house” for the Lord—a temple in which to place the Ark. The temple stood as God’s definitive dwelling place among his people. It was the heart of liturgical and social life, a place of daily sacrifice, annual pilgrimage, repentance, and festival.

Thus, its destruction by the Babylonians in 586 BC marked an unprecedented time of mourning. The people were exiled, and the holy city of Jerusalem suffered immense devastation. The book of Lamentations tells us that “The roads to Zion mourn, empty of pilgrims to her feasts. / All her gateways are desolate, her priests groan, / Her young women grieve; her lot is bitter” (Lam 1:4). Because the Lord had “rejected his altar” and “spurned his sanctuary” (2:7), his people cried out: “Why have you utterly forgotten us, forsaken us for so long?” (5:20). Even when the Persian King Cyrus’ policies of religious tolerance allowed the Jews to return to the land, the newly rebuilt temple did not retain the glory of its predecessor. It was smaller, more modest in appearance, and it did not contain the Ark. Furthermore, it was encompassed in a land ruled by other nations; after the Persians, the Greeks and then the Romans came to power.

The Old Testament ends on a note of expectation. The message of the prophets during the exile spoke of two interconnected hopes: first, that the messianic king promised to David long ago would eventually come to take his throne and rule forever; and second, that God himself would come again to his people to establish his kingdom, a kingdom where all peoples of the earth would be destined to worship the Lord and the words of Jeremiah would come true, “They shall be my people, and I will be their God” (Jer 32:38).

Jesus as the Real Presence of God in the New Testament

The New Testament authors speak of something unfathomable in the history of Israel: the two hopes that emerge from the Old Testament not only intertwine but become one in the person of Jesus Christ. For the apostolic Church, Jesus was both the long-awaited messiah, who could rule forever through his resurrection, and the coming of God to establish his kingdom. The theophanies at Horeb/Sinai find their fulfillment in him. Moses receives the Law from God, and yet Jesus ascends a mountain to reveal himself as the Lawgiver in the Sermon on the Mount. The mystery of the burning bush is recast on Mt. Tabor at Jesus’ transfiguration, where his humanity is blindingly illuminated by the radiance of his divinity, yet not destroyed. Jesus not only heals but forgives sins, something only God could do (Mk 2:5–7). He mysteriously tells others, “Before Abraham came to be, I Am” (Jn 8:58). His words and actions lead some of the religious leaders of his fellow Jews to charge him with blasphemy (Mk 14:64).

Indeed, the passages in the New Testament that point to the divinity of Christ and, therefore, Jesus as the presence of God in history are too numerous to list. The declaration of the New Testament is unmistakable: God has become present to his people in a remarkable and definitive way, as the Son of God who has “pitched his tent” (eskēnōsen in the Greek of John 1:14) in history, as a divine person who loves humanity so much that he has taken it to himself, as one who breathes, smiles, feels pain, and has a beating heart. Greater than the theophanies of the past, God himself has now come to be with us: Emmanuel (Mt 1:23).

The climax of the New Testament is the unjust treatment of God-made-man, his sentencing before Pontius Pilate, his excruciating death by crucifixion, and his miraculous resurrection. And though he eventually ascends into heaven, to once more sit at the right hand of the Father, the apostles and their collaborators tell us that he arranged a way in which to be continually present with his people till the end of time. This is the great gift of the Most Holy Eucharist.

For biblical passages in eucharistic theology, one easily thinks of the Bread of Life discourse in John 6, where Jesus’ flesh and blood are “true food” and “true drink,” and those who consume it will be raised by him on the last day (Jn 6:54–55). Still, the heart of eucharistic teaching and spirituality is found in the account of the Last Supper, surely the most familiar text for Catholics, since the words of Christ spoken there occur in every Mass. Matthew, Mark, Luke, and even Paul in his First Letter to the Corinthians repeat the same words of Jesus in reference to the bread and wine, a sure sign that they stem from the earliest tradition and are traceable back to Jesus himself.[4]

Jesus and his disciples come to Jerusalem to celebrate Passover, a living commemoration of the ritual that freed the Israelites from the grip of Egypt. In the time of the Exodus, Jewish families had each sacrificed a lamb, spreading its blood on the doorposts and lintel of their homes as a sign for the Lord to pass over them when striking down the firstborn of the land (Ex 12). So, too, were they to roast the lamb and eat it with unleavened bread, a symbol of the haste with which they would leave Egypt. In the second temple period of Jesus and his disciples, the Passover was celebrated in Jerusalem, first at the temple, where the lambs would be sacrificed, and then in individual homes, where fathers would lead their families in a domestic liturgy of remembrance, recalling the Lord’s salvific deeds and partaking of the lamb, unleavened bread, and wine as if a window to the past had been opened up at the family table.

In what would surely be a surprise to Jewish observers, Jesus celebrates the meal not with his blood family, so to speak, but with his disciples.[5] More shocking still, the New Testament writers make no mention of a roasted lamb. Rather, in taking up the unleavened bread, Jesus speaks, “This is my body, which will be given for you” (Lk 22:19). Then, raising a cup of wine, he continues, “This is my blood . . . , which will be shed for many” (Mk 14:24). The words of institution and the absence of the lamb on the table speak the same truth in unison: Jesus is the Passover Lamb of the new covenant, a fact that will be better realized by his followers when they see him upon the Cross, his blood staining its wood like the lamb’s blood that marked the entryways of Israelite homes long ago. John, while agreeing with the other evangelists that this supper was shared at the time of Passover, does not repeat the words of institution. Yet, the narrative portion of his gospel opens with John the Baptist’s words, at first enigmatic but now made clear: “Behold, the Lamb of God, who takes away the sin of the world” (Jn 1:29). Paul, in the earliest of the writings that contain the words of institution, tells us that he received these words—“This is my body” and “This cup is the new covenant in my blood”—and, thus, delivers them with fidelity (1 Cor 11:23–26). Therefore, Christians, following the command of the Lord to “Do this in remembrance of me,” have continued to gather with the successors of the apostles (the bishops) and the priests ordained to help them in their ministry to celebrate this great sacrament in which bread and wine become the Body and Blood of the Lord. In the Eucharist, the power of the sacrifice of Calvary emerges from the past into our own time, and the Lord, now ascended in his glorified body in heaven, becomes present in an unparalleled way in, through, and for the sake of his Church.

A Eucharistic Spirituality

Why has God done this? Why has he given the Church such an amazing gift? It is because he loved us “to the end” (Jn 13:1). The God who gains nothing from us yet holds each of us in existence—this same God longs to be with us, even thirsts for us. A catechist must experience this divine thirst in the silence of prayer and, in response, let her own thirst for the Lord’s presence well up inside.

Why has God done this? Why has he given the Church such an amazing gift? It is because he loved us “to the end” (Jn 13:1). The God who gains nothing from us yet holds each of us in existence—this same God longs to be with us, even thirsts for us. A catechist must experience this divine thirst in the silence of prayer and, in response, let her own thirst for the Lord’s presence well up inside.

It is a bedrock truth of catechesis that one cannot give what one does not have. We must, therefore, encounter the Lord in the Eucharist ourselves should we desire our hearers to do the same.

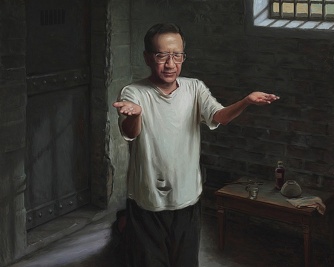

I am reminded of the story of Ven. Francis Xavier Nguyen Van Thuan, the Vietnamese cardinal who was imprisoned by communists for thirteen years, nine of them in solitary confinement. There, in the darkness of prison, he celebrated Mass with a crumb of bread and a drop of wine upon the altar of his hand. He would reserve a consecrated crumb in a tabernacle made of paper, with fellow prisoners taking turns staying up through the night in adoration of the Blessed Sacrament. The immensity of the revelation of the Word of God, that he is the God of presence and the one who loves us to the end, and the power of the Church’s doctrine of transubstantiation—all of this comes together and becomes alive on the palm of a man in a prison cell. This same Real Presence is there waiting for us at every Mass and in every tabernacle. If a revival is to be sparked in our land, then it will begin there, in communing with the Lord and adoring him, letting him transform our hearts so that we might be living tabernacles who will bring his presence to every corner of our communities.

Brian Pedraza, Ph.D. is associate professor of theology at Franciscan Missionaries of Our Lady University in Baton Rouge. His latest book, Catechesis for the New Evangelization, was published by Catholic University of America Press in 2020.

Notes

[1] Committee on Doctrine, The Mystery of the Eucharist in the Life of the Church (Washington, DC: USCCB, 2021).

[2] See, for instance, St. Thomas Aquinas, Summa Theologiae III, q. 75.

[3] This is Gerard Manley Hopkins’ translation of the first verse of St. Thomas’ Adoro te devote, quoted in CCC 1381.

[4] John opts, instead, for a description of eucharistic charity in his disciples and a view into the communion between the Father and Son in the Spirit of which the communion of his disciples and their hearers will share. See John 13–17. I have already mentioned the Bread of Life discourse in chapter 6:35–71, a eucharistic teaching that gives powerful witness to the Real Presence of Jesus in the sacrament.

[5] For catechists, the most helpful book for understanding the development of Passover from the time of the Exodus to that of Jesus is Brant Pitre’s Jesus and the Jewish Roots of the Eucharist (New York: Doubleday, 2011).

This article originally appeared on pages 10-13 of the printed edition.

Art credit: Francis Xavier Nguyen Van Thuan by Australian artist Paul Newton

This article is from The Catechetical Review (Online Edition ISSN 2379-6324) and may be copied for catechetical purposes only. It may not be reprinted in another published work without the permission of The Catechetical Review by contacting [email protected]