Maybe it’s too much of a stretch to say that an unmarried tailor who lived with his mother is the reason communism fell in the west. Then again, maybe it’s not.

Maybe it’s too much of a stretch to say that an unmarried tailor who lived with his mother is the reason communism fell in the west. Then again, maybe it’s not.

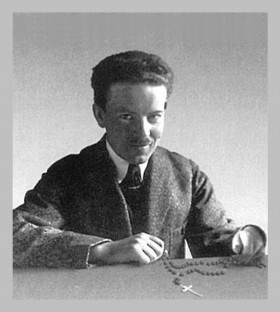

Venerable Jan Tyranowski was, in many respects, an ordinary working class bachelor. But when he was 35, a homily changed his life. “It is not difficult to become a saint,” the priest said, and Tyranowski believed him. He began reading the Carmelite mystics and praying up to four hours a day. When many of Poland’s priests were sent to death camps in 1940, one of those left behind asked Tyranowski to become more involved in youth ministry.

That’s where he met Karol Woytyla. The young man who would become pope was just a 20-year-old in youth group, but his relationship with Tyranowski changed everything. Karol had become unsure about the wisdom of putting so much emphasis on the Blessed Mother, but Tyranowski pointed him to St. Louis de Montfort, thus shaping the life and papacy of the man who would be the most Marian Pope since St. Peter. Perhaps more importantly, Tyranowski’s work with the young Woytyla (especially after Karol lost his father in 1941) greatly influenced Wotyla’s vocational discernment. A friend of St. John Paul’s from that same youth group insists that John Paul owed his priestly vocation to the single tailor.

Tyranowski died only a few months after Fr. Woytyla was ordained. He didn’t live to see his young friend consecrated bishop or elected pope. He didn’t see the work of the Polish pope break the stranglehold of communism on Poland and her neighbors. Through it all, though, St. John Paul kept a picture of his youth minister on his desk, a single man whose life changed the world.

A Church of Single Saints

Tyranowski isn’t the only unmarried person ever to have a cause for canonization opened, either. While the canon of saints is filled with priests and religious and even a good number of married people, there are plenty of single laypeople whose lives of holiness have given glory to God down through the ages. There’s Bl. Piergiorgio Frassatti, of course, and Bl. Chiara Badano, along with American Servants of God Julia Greeley and Dorothy Day. Bl. Francisca de Paula de Jesus was an illiterate freed slave, while St. Charles Lwanga was an attendant to a king. Some were martyred young, like Bl. Isidore Ngei Ko Lat and St. Anna Wang, while others lived long lives, like Bl. Catherine Jarrige, who smuggled priests during the French Revolution. Some longed for other vocations, like Bl. Carlos Rodriguez whose chronic illness made a priestly vocation impossible; others, like the doctor St. Giuseppe Moscati, seem to have been called distinctly to a single vocation lived in the world.

Of course, all saints were once single laypeople. It’s easy to remember them in the state of life in which they died, but some spent many years living in the world as single people. St. Gianna Molla, for example, was married just before she turned 33—at least 5 years after the average Italian woman—and Bl. Mary of the Apostles didn’t find her vocation as a sister until she was 55.

What unites them isn’t age or race or gender or social status. What unites them is a life handed over to the Lord, a radical openness to following God’s will, and a heart inflamed with love for him.

Holiness in the In-Between

For those who are unintentionally single, years and years of watching friends get married and take vows and get ordained can be trying, particularly when it seems as though life (and the pursuit of holiness) begin when you finally commit yourself to a vocation. Even those who have taken private vows or otherwise feel called to a lifetime of singleness can feel isolated in a Church that seems so geared toward vocations to marriage or religious life.

But what if we treated our single lives not as a waiting period, as though years of prayer and work and service are nothing more than an interminable line at the DMV, but as a call to holiness? What if we lived for Jesus now, pursuing radical holiness in the in-between instead of putting it off until our “real life” begins?

There’s a story told of St. Aloysius Gonzaga that he was once playing billiards with his friends when one asked the others what they would do if they discovered that the world was going to end the next day. Being appropriately pious, one said that he would go to confession, another that he would spend the whole night in prayer, a third that he would go door to door inviting people to repent. Aloysius just answered, “I would finish this game of billiards.”

St. Aloysius didn’t need to make any enormous changes to prepare himself for death; he was already living entirely for Jesus, billiards and all.

Life in the modern world is full and complicated, with many single people holding down multiple jobs, struggling through endless commutes, and trying desperately to build community, fit in prayer time, and maybe find a date every once in a while. Single life can feel like a hectic season to survive, not an opportunity for radical holiness.

Yet the invitation to follow Jesus doesn’t come only after vows—religious or marital. At the moment of our baptism, God begins fashioning a halo for us. Knowing the shape that our lives will take, our sin and shame, the years of longing and wandering and wondering, still he calls us his own. Still he calls us to be saints.

Radical Availability

What does that look like for single people? As with the single saints mentioned above, it can certainly vary. But there is a freedom in the single life, an availability that priests and religious and parents of small children don’t have. For most, there is time to pursue the Lord and serve his people, often in a profound way.

There is, in the single life, a radical availability that many people don’t notice because their days are so full. But those who are unmarried have the ability to make time for prayer and for service in ways that others can’t. Those who live in major cities can likely make it to Mass most days; indeed, most singles could probably manage an hour of prayer each day if they chose to schedule their lives around it. There’s time to be a mentor, to volunteer at a group home, to lead a Bible study, to coach a soccer team. There isn’t time for all of it, but there’s time for some.

It’s terribly easy, if you’re single but hoping to be married, to become bitter at the years you’ve wasted while each relationship fizzles. Or perhaps you’re quite happy with your bare ring finger—and with the years of living for yourself before a future vocation steps in to demand holiness. Maybe you’re too confused about God’s call to feel either.

Whatever your current feeling about your single status, your way of life right now is a blessing. Or at least it has the potential to be, if you sit down with the Lord and ask him, “What would my single life look like if I were a saint?” Not just “if I were going to become a saint eventually” but “What if I were a saint right now? What would I do in my job, with my roommates, during my commute, and with my dating apps?” What would your prayer life look like? What holy hour would you sign up for? Where would you serve at your church? With whom would you build community? How would you spend your money?

Single life can be the world’s most frustrating waiting game or it can be a novitiate, a preparation for a future vocation (or for heaven) by a period of intense prayer and service. Unlike other vocations, it doesn’t sanctify us by its very nature; but if we choose to invite God into our singleness, he can make us holy in and through our state in life.

Ven. Jan Tyranowski was made a saint in the ordinary suffering of his unmarried life. It wasn’t martyrdom or theological acumen or moments of heroism that made him holy, but a decision. He decided that he would live fully for Christ, and so he did. He made time for prayer. He made time for service. And because he gave his life over to God and neighbor, he became a man whose life gave glory to God—and changed the course of human history forever. If he had waited to become a saint until after he was married or ordained or professed, God alone knows where we would all be today.

Meg Hunter-Kilmer is a hobo missionary. After 2 theology degrees from Notre Dame and 5 years as a high school religion teacher, she quit her job in 2012 to live out of her car and preach the Gospel to anyone who would listen. 50 states and 25 countries later, this seems to have been a less ridiculous decision than she initially thought. She blogs at www.piercedhands.com.

This article originally appeared on pages 26-27 of the printed edition.

Photo of Venerable Jan Tyranowski: Public domain image from Wikimedia Commons.

This article is from The Catechetical Review (Online Edition ISSN 2379-6324) and may be copied for catechetical purposes only. It may not be reprinted in another published work without the permission of The Catechetical Review by contacting [email protected]