In Death Comes for the Archbishop, Willa Cather’s sweeping novel describing the evangelistic efforts of the first archbishop of Santa Fe, the author vividly describes the archbishop’s reaction upon hearing of the miraculous vision of Our Lady of Guadalupe. Marveling at the loving tenderness of the Blessed Mother to St. Juan Diego and his people, the archbishop muses: “the miracles of the Church seem to me to rest not so much upon faces or voices or healing power coming near to us suddenly from afar off, but upon our perceptions being made finer so that . . . for a moment our eyes can see and our ears can hear what is there about us always.” He takes this idea further, saying, “where there is great love there are always miracles. One might almost say that an apparition is human vision corrected by divine love.”[1]

In Death Comes for the Archbishop, Willa Cather’s sweeping novel describing the evangelistic efforts of the first archbishop of Santa Fe, the author vividly describes the archbishop’s reaction upon hearing of the miraculous vision of Our Lady of Guadalupe. Marveling at the loving tenderness of the Blessed Mother to St. Juan Diego and his people, the archbishop muses: “the miracles of the Church seem to me to rest not so much upon faces or voices or healing power coming near to us suddenly from afar off, but upon our perceptions being made finer so that . . . for a moment our eyes can see and our ears can hear what is there about us always.” He takes this idea further, saying, “where there is great love there are always miracles. One might almost say that an apparition is human vision corrected by divine love.”[1]

With the Incarnation, undertaken that "we might know God’s love” (CCC 458), miracles abound. Jesus’ first miracle is requested by his mother at a marriage celebration (Jn 2:1–12). A paralyzed man’s friends, out of love, take the extraordinary step of lowering him through someone else’s roof, and he is miraculously healed (Lk 5:17–26, cf. Mt 9:1–8, Mk 2:1–12). Lazarus is raised from the dead (Jn 11: 1–44). Jesus worked miracles not only to validate what he claimed of himself but also to reveal that, in a civilization of love, such things are common and to be expected.

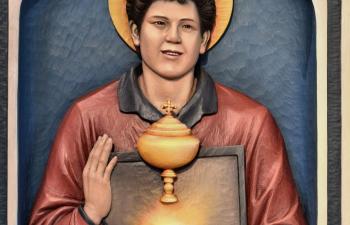

Miracles continue to happen today, both in the public eye (see Regina Deighan’s article on eucharistic miracles) and in more hidden ways (see Dr. Gerard O’Shea’s essay describing a healing his daughter received). One of my extraordinary online graduate catechetics students, Sr. Sarah Nakyesa, TOR, from Uganda, tells a striking story of a miracle she experienced in her early twenties: “I was walking to the nearby parish church to attend Mass, and I met a violent madwoman attacking whoever passed her by. By the time I noticed danger, it was too late for me either to run away or to stop, so I decided to just pass her with caution. To my surprise, and to the surprise of all those who were trying to run away, this madwoman knelt down and made the sign of the cross continuously until I passed her by.” This experience made a deep impression on Sr. Sarah, who sees in it a miracle both for her and for the woman she passed.

One thing that becomes clear in the miracles of Jesus is that he prioritizes spiritual healing over the healing of our bodies, even as there were many physical healings he performed. Indeed, the physical healings are always oriented toward the inner healing of the ravages of sin, which are of far greater consequence in the mind of our Lord. The Catechism makes clear that Jesus “did not come to abolish all evils here below, but to free men from the greatest slavery, sin, which thwarts them in their vocation as God’s sons and causes all forms of human bondage” (549). To the paralyzed man described above, Jesus first said, “your sins are forgiven” (Lk 5:20) before he said, “rise, pick up your stretcher, and go home” (Lk 5:24).

These miracles of the past are all extraordinary, to be sure. But in his article, Dr. John Bergsma helps us to understand something very important about miracles occurring today. Christ instituted the sacraments so that his healing and miraculous power would continue to be made manifest throughout all of time. Certainly, there are many miracles that happen outside of the sacraments—but the sacramental life is meant to be our ordinary contact with the healing and reconciling power of Christ.

To demonstrate this, in its introduction to the sacraments, the Catechism draws upon the account of the healing of the woman with the hemorrhage in the Gospel of Luke (8:43–48). This woman, after exhausting all the natural means at her disposal, approaches Jesus with great faith and confidence. And, on account of her faith, she is healed just by touching the tassel on his cloak, as Jesus perceives that “power has gone forth from” him (v. 46). On page 277 of its first edition, beneath the image depicting this healed woman, the Catechism describes the healing power sacramentally available to us: “The sacraments of the Church now continue the works which Christ had performed during his earthly life (cf. no. 1115). The sacraments are as it were ‘powers that go forth’ from the Body of Christ to heal the wounds of sin and to give us the new life of Christ (cf. no. 1116).”

Where there is great love, there are miracles. In the sacraments, we encounter the love of God—and his miraculous, healing power—most profoundly.

Dr. James Pauley is Professor of Theology and Catechetics at Franciscan University of Steubenville.

Note

[1] Willa Cather, Death Comes for the Archbishop (New York: Vintage Books, 1990), 50.

This article is from The Catechetical Review (Online Edition ISSN 2379-6324) and may be copied for catechetical purposes only. It may not be reprinted in another published work without the permission of The Catechetical Review by contacting [email protected]