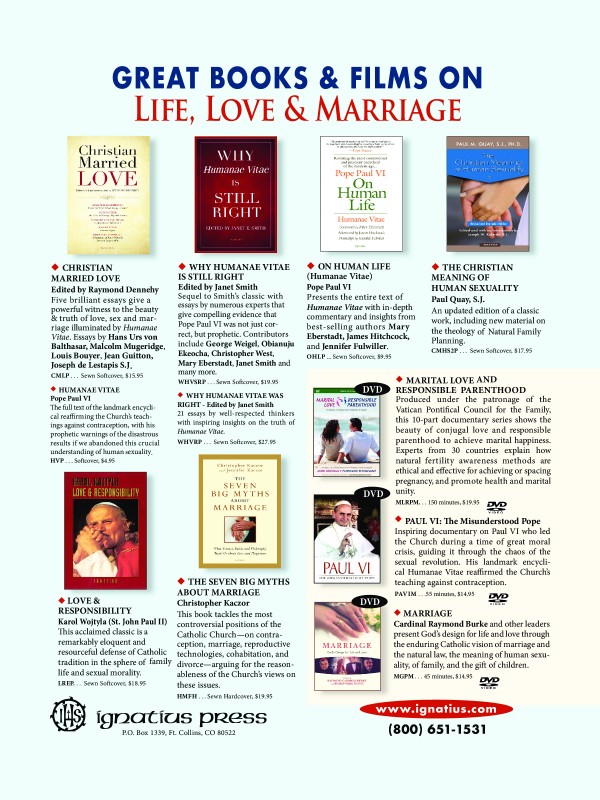

AD: Great Books & Films on Life, Love & Marriage from Ignatius Press

This is a paid advertisement. To view more books from Ignatius Press click here, or call (800)651-1531.

Catequesis para Niños: La formación de una cultura de oración en el hogar

¿Qué recuerdas de tu primer día de clases del primer grado de la escuela primaria? ¡Mi recuerdo ha dado a mi vida una finalidad profética y un valor que perdurará toda la vida! Tras pasar lista y asignar sus lugares a sus 120 alumnos (¡no es ningún error tipográfico esto!), la menuda Sr. Santa Rosa nos avisó que nuestra primera lección sería la más importante de nuestra vida. Repartió nuestro primer libro de catecismo y nos indicó que lo abriéramos en la primera lección. Con lápiz en mano, encerramos con un círculo las preguntas número uno, dos, y tres. La Hermana nos instruyó sobre el sentido de las palabras y nos dijo que les pidiéramos a nuestros papás que nos enseñaran cómo decir las palabras con los ojos cerrados.

Mi mamá vigilaba la hora de las tareas. Me asombró cuando, sin mirar el libro, conocía las respuestas a las tres preguntas. Más asombrosa aún fue la plática durante la cena esa noche. Mi mamá dijo, “Pat, dile a tu papá qué aprendiste en la escuela hoy”. Le miré derechito a los ojos de mi papá y declaré con convicción, “Aprendí porqué Dios me creó”. Sin titubear en absoluto, mi papá proclamó, “Pat, Dios te creó para conocerlo, amarlo, y servirlo en este mundo, y para que seas feliz con Él para siempre en el próximo”. La respuesta que me dio mi padre tuvo una influencia exponencial porque, con justa razón, se había ganado el apodo de “Daddy Old Bad Boy” (Papá Viejo Niño Travieso). Su mal comportamiento era legendario y por eso todos los años los Reyes Magos le dejaban carbón en su bota navideña. Entonces, cuando este hombre sabía por qué Dios me había creado, ¡me tragué el anzuelo y abracé totalmente esta creencia! Haciendo eco del sentimiento de Robert Frost, “eso ha hecho toda la diferencia.” [i]

El llegar a conocer a Dios – y crecer en ese conocimiento y la experiencia del mismo a lo largo del tiempo – es nuestro llamado universal, nuestra vocación primaria. El conocimiento de Dios conduce al amor. ¡Una persona que no ama a Dios es una persona que no conoce a Dios! Y nosotros mismos - cuando amamos a una persona, no podemos menos que desbordar en el servicio que le damos por amor.

La oración: tanto acción como actitud

Como “Primeros Mensajeros del Evangelio”[ii] los padres de familia tienen el privilegio y la responsabilidad de presentarles Dios a sus hijos; de sensibilizarles a que reconozcan los caminos de Dios; de aprender a hablar con Dios; y de responderle a Dios de manera apropiada según su edad. La oración es el hilo conductor para todos estos objetivos.

¿Qué es la oración? Las definiciones abundan. Hasta Wikipedia interviene sobre el tema. Mi definición nuclear, y es la que ofrezco a los padres de familia actuales, proviene de ese mismo catecismo de primer grado: “La oración es elevar nuestra mente y nuestro corazón a Dios”. La oración puede ser vocal o mental, formal o informal, privada o colectiva, programada o espontánea. La oración cambia con la edad y las etapas de la vida, así como la calidad y el estilo de comunicación cambia con el tiempo entre personas quienes estén creciendo en su relación.

La oración es comunicación con Aquél que nos conoce mucho mejor que nosotros mismos nos conocemos, y que nos ama más allá de nuestra capacidad para comprender tal amor. Sin tregua y sistemáticamente Dios nos comunica su amor y su voluntad que da vida, aunque a menudo no nos demos cuenta y estemos inatentos. Frecuentemente, el ajetreo de la vida bloquea nuestro reconocimiento de los movimientos de Dios. Los ruidos de nuestro ambiente ahogan los susurros del amor de Dios. Independientemente de nuestra percepción, Dios sigue hablando, tendiéndonos la mano, y ofreciendo su amistad.

La oración es acción y actitud. Toda persona, lugar, estímulo, o evento que eleva nuestra mente y nuestro corazón a Dios puede ser catalizador para la oración. Las prácticas espirituales comprendidas y adoptadas voluntariamente con fidelidad elevan nuestra conciencia espiritual. Los ambientes, costumbres y ritos que tutoran al alma o recuerdan la presencia de Dios pueden incitar un santo deseo y afecto.

Children's Catechesis: Forming a Culture of Prayer within the Home

What do you remember of your first day of Grade One? My memory gave prophetic purpose and life-long value to my life! After taking roll and assigning seats to her 120 students (not a typographical error!), petite Sister St. Rose announced that our first lesson would be the most important lesson of our lives. She distributed our first catechism book and directed us to lesson one. With pencil in hand, we circled question numbers one, two, and three. Sister instructed us in the meaning of the words and told us to have our parents teach us how to say the words with our eyes closed. My mother proctored homework time. She amazed me when, without looking at the book, she knew the answers to the three questions. More amazing yet was dinner conversation that night. Mom said, “Pat, tell dad what you learned at school today.” I looked my dad straight in the eye and declared with conviction, “I learned why God made me.” Without skipping a beat my father proclaimed, “Pat, God made you to know him, to love him, and to serve him in this world, and to be happy with him forever in the next.” Dad’s reply had an exponential influence because he had justly earned the nickname of “Daddy Old Bad Boy.” Dad’s misbehaviors were legendary and yearly Santa Claus deposited coal in his stocking because of it. So, when this man knew why God made me, I embraced the belief hook, line, and sinker! Echoing the sentiment of Robert Frost1, “that has made all the difference.” Coming to know God—and growing in that knowledge and experience over time—is our universal call, our primary vocation. Knowledge of God and the ways of God leads to love. A person who does not love God does not know God! And whenever any of us love another person we can’t help but overflow into service for them. Prayer: Both Action and Attitude As “First Heralds of the Gospel”2 parents bear the privilege and the responsibility to introduce their children to God; to sensitize them to recognize the ways of God; to learn how to speak to God; to distinguish God’s voice and will from other voices; and to respond to God in age-appropriate ways. Prayer is the common thread for these goals. What is prayer? Definitions abound. Even Wikipedia weighs in on the topic. My core definition, and one that I offer to contemporary parents, comes from that same first grade catechism: “Prayer is the lifting of our minds and hearts to God.” Prayer can be vocal or mental, formal or informal, private or corporate, scheduled or spontaneous. Prayer changes through the ages and stages of one’s life, just as the quality and style of communication changes over time between persons who are growing in relationship. Prayer is communication with the One who knows us better than we know ourselves and Who loves us beyond our ability to comprehend such love. Consistently God communicates God’s love and life-giving will, though we are frequently unaware or inattentive. Often the busyness of life blocks recognition of God’s movements. The noises of our environment drown out the whispers of God’s love. Regardless of our awareness, God continues to speak, to reach out, and to offer friendship. Prayer is both an action and an attitude. Any person, place, stimulus, or event that lifts our minds and hearts to God can be a catalyst of prayer. Spiritual practices that are understood and faithfully embraced raise our spiritual consciousness. Environments, customs, and rituals that tutor the soul or recall God’s presence can stir holy desire and affection.

Desde los Pastores: Una catequesis de pertenencia

El papel de la familia como modelo catequético para el ministerio hispano

From the Shepherds: A Catechesis of Belonging

The Role of the Family as the Catechetical Model for Hispanic Ministry

To read this article in Spanish, click here.

Changing the Subject: Forming People to Encounter Mystery

There is a scene in the film Good Will Hunting where Sean (Robin Williams) and Will (Matt Damon) share a pivotal conversation on a bench overlooking a swan-filled lake. The week before, Will quickly and incisively interprets a painting that Sean had created and hung in his office.

There is a scene in the film Good Will Hunting where Sean (Robin Williams) and Will (Matt Damon) share a pivotal conversation on a bench overlooking a swan-filled lake. The week before, Will quickly and incisively interprets a painting that Sean had created and hung in his office.

Encountering God in Catechesis

The most memorable statement from the angry email was, “This is not what my son signed up for.” Three weeks prior to departure, I had finally informed our youth group of some final needs for our summer mission trip to Hardin County, Kentucky: a sleeping pad or air mattress, as we would likely be sleeping on a floor, and a swim suit—mainly for the tarpaulin-screened bucket baths we would be taking. “Kevin McQuiggen’s” mother was distressed by the conditions in which her son would be living for the week of the trip. The theme for the week was Catholic social teaching, so I replied how our “difficulties” for the week would be a good exercise in solidarity with the people with whom we would be staying to try to assuage her objections.

My town has only a few people I would consider “rich.” The population is mainly mid to lower-middle-class. Kevin’s family is solidly middle-class, and his parents are understandably happy that their children have a comfortable life. Kevin was a regular altar-server, but wasn’t involved in much else at our parish. When he did attend some youth activity it was for him primarily a social event. I was somewhat surprised when his mother turned in the paperwork to have him make the trip, really. The first time I had tried to recruit some teens after a Mass he had jokingly asked, “Can’t we just write a check and stay home?”

Find out what happens to Kevin and how God changes his life. And find out about Laura, who believes God doesn't love her...can't love her.

Editor's Reflections: Learning to Live the Catholic Faith

What does it mean to learn the Catholic Faith? Certainly there are names and historical periods that are important. Essential revealed truths must be understood. This is so because it is God’s revelation that has been entrusted to the Church, a revelation that all the baptized have a right and a need to hear and understand over a lifetime. There is a story to grasp, that of salvation history and our particular place in it.

AD: Online Courses that Integrate Faith Development & Digital Media

This is a paid advertisement in the July-September 2018 issue. Advertisements should not be viewed as endorsements from the publisher. To learn more about the online courses offered from Pauline Media visit www.bemediamindful.org.

Hawaiian Inculturation: Island Wisdom and the Eternal Truth of Christ

As a young boy, my grandfather (kupuna kāne: KOO-poonah KAH-nay) taught me important and practical knowledge that was unique to island-living: fishing, taro farming, herb collecting for traditional Hawaiian medicines, and underground cooking with lava rocks and banana leaves. He also taught me, as generations before him had done, those ethical principles that guide Hawaiian culture. Some of these include: the importance of song (mele: may-lay) and storytelling (mo'olelo: moh-oh-lay-loh) in handing down our culture, the necessity of caring for the land (Mālama 'Āina: MAH-lah-mah AE-nah), and the indispensability of reconciliation, healing, and restoration (ho'oponopono: hoh-oh-poh-noh-poh-noh). Growing up before the age of Twitter and Facebook, I assumed that children all over the world learned these values. I did not realize that I was receiving an ancient and rare wisdom unique to the Hawaiian Islands. During my formative years at Franciscan University, the ancient wisdom of my Hawaiian heritage co-mingled with the universal truths and beauty of the Catholic faith that enlivened my understanding of and love for both. The more I learned about our rich Catholic faith, the more I realized that many of the lessons my grandfather taught me were the perfect primer for me to engage, understand, and internalize many eternal truths of the faith. It is as if God had inspired essential aspects of the Hawaiian pre-Christian culture I learned from my grandfather with values, significant expressions, and a living tradition that easily transitioned to original expressions of the Christian life, celebration, and thought. Searching the Depths of a Culture This reality is encompassed in the Catholic concept of “inculturation,” which, in short, is the process of examining the roots of a culture through the lens of the Gospel and to "bring the power of the Gospel into the very heart of culture and cultures.”[2] The term “inculturation” is taken from various documents of the Magisterium.[3] The concept of inculturation, though championed and elegantly explained in recent times by Pope St. John Paul II, is not new. The root of inculturation is the example of Christ himself. The Second Person of the Trinity was incarnated and inserted into the particular culture of a particular time. He engaged the apostles within their own culture and gave them the fullness of Truth. Within a century, they, in turn, spread the Gospel across Eurasia. Marks of their inculturation to the different peoples they evangelized can still be seen today in the glorious array of differing liturgical expressions throughout the 24 sui iuris churches that make up our Catholic Church in Hawaii.