AD: Pauline Books & Media—Books on Discernment, Saints and more

This is a paid advertisement in the July-September 2018 issue. Advertisements should not be viewed as endorsements from the publisher. To find out more about products from Pauline Books & Media call 800-878-4463 or visit www.PaulineStore.org

Catholic Education—A Road Map: The Teaching Methods of Maria Montessori

Maria Montessori - Devout Catholic Educator

The name Maria Montessori has been associated with a highly successful educational method for over a century. What is not well known about Montessori is that she was a sincere Catholic, who received enthusiastic endorsement from the highest authorities in the Church. As early as 1910, Pope Pius X was familiar with her work and commended it for its capacity to regenerate the child. His successor, Benedict XV had a two-hour private audience with Montessori regarding her methods, and then sent her a letter asking to set up an organization to promote her work more broadly. Further private audiences and encouragement followed from Pope Pius XII and John XXIII. Speaking in 1970, Pope Paul VI observed that "Maria Montessori's method of religious pedagogy is an extension of her secular pedagogy; it is naturally founded on the latter and forms its crown." Indeed, she believed that the principles expressed in the Sacred Liturgy of the Catholic Church exactly matched her discoveries in the broader field of education. Pope John Paul II reiterated Paul VI's observations and added that "the name of Montessori is clearly representative of all women who have made important contributions to cultural progress."

Montessori had not always been a devout Catholic. In her youth she had been a sceptic. Her son, Mario, wrote that his mother had undergone a dramatic conversion brought about by what she witnessed in the children she worked with. "She left her career, she left her brilliant position among socialists and feminists, she left the university, she left even the family and followed him [Christ]." While they applauded many of her ideas, it was the characteristically Catholic dimensions of Montessori's method which brought her into conflict with the American philosophers, John Dewey and his disciple, William Kilpatrick. The anti-Catholic nature of the American educational establishment in the early part of the twentieth century was sufficient to discredit Montessori's insights until the 1950s, when they were re-examined more dispassionately.

Formación religiosa incluyente para niños: Tres partes, una comunidad

En el año 2005, la Conferencia de Obispos Católicos de los Estados Unidos publicó el documento titulado, The National Directory for Catechesis [El directorio nacional para la catequesis], lo cual declara, “toda persona con discapacidad tiene necesidades catequéticas que la comunidad cristiana tiene el deber de reconocer y satisfacer. Toda persona bautizada con discapacidad tiene el derecho a una catequesis adecuada y merece los medios para desarrollar su relación con Dios.” [1] Mi interés y participación en la formación religiosa de niños con discapacidades tiene sus raíces en mi experiencia personal. Al buscar respuestas acerca de lo que mejor nos convenía como familia, descubrí que nuestra historia era común; y aunque algunos estudiantes reciban una catequesis en su hogar, los estudiantes que se ausentan de los programas parroquiales para la formación de la fe se pierden de un elemento fundamental de la fe cristiana: la comunidad.

¿Dónde están los niños con discapacidades?

Como la mayoría de los padres de familia, nunca me imaginaba que mi hija iba a necesitar una educación especial. Mi esposo y yo teníamos el sueño y el objetivo de educar a nuestros hijos en una escuela católica desde el jardín de niños hasta el final de la educación media superior o grado 12. Cuando nuestro quinto hijo, Grace, entró al kínder, aquel sueño comenzó a desmoronarse. Sabía, desde el primer día, que Grace iba a necesitar de una ayuda adicional para mantenerse sentada, hacer filas y esperar su turno. De lo que aún no me daba cuenta era que su falta de contacto visual, su incapacidad para recordar los nombres de los miembros de la familia extendida y su obsesión con los dinosaurios eran indicadores de un trastorno del Espectro Autista, un diagnóstico que no recibimos sino hasta el verano posterior a su año en jardín de niños. Las lagunas de Gracie en cuanto a sus habilidades comunicativas fueron percibidas como una falta de respeto, su falta de habilidades sociales como una falta de amabilidad para con sus compañeros de clase, y sus sensibilidades sensoriales como un comportamiento inmaduro, incluso salvaje. Mi esposo y yo tomamos entonces la decisión de soltar nuestro sueño, y Gracie pasó a formar parte del 13 por ciento de niños que reciben servicios de educación especial en la escuela pública. [2] Sabíamos que teníamos que proporcionarle a nuestra hija su formación en la fe; elegimos enseñarle en casa desde el principio. Durante tres años nosotros mismos le enseñamos a Gracie y le preparamos para su Primera Reconciliación y su Primera Comunión utilizando los materiales para la educación en la fe de nuestra parroquia.

La mayoría de los niños que asisten a los programas católicos de formación en la fe provienen de escuelas públicas. Si el 13% de los niños que asisten a la escuela pública reciben educación especial, es de esperar que el 13% (uno de cada ocho) de los alumnos que asisten a programas de educación en la fe requieren de algún tipo de apoyo educativo para optimizar sus resultados de aprendizaje. San Juan Pablo II definió el resultado de aprendizaje óptimo para la educación religiosa: “el fin definitivo de la catequesis es poner a uno no sólo en contacto sino en comunión, en intimidad con Jesucristo…”.[3] En la tradición católica, esto también abarca la preparación y la recepción de los Sacramentos de la Reconciliación, la Eucaristía y la Confirmación.

El número de estudiantes con discapacidades que asisten a programas de formación en la fe no corresponde a las estadísticas. Es posible que los padres de familia no revelan toda la información acerca de las necesidades de sus hijos o simplemente no les inscriben. Las razones varían. Los padres de niños con discapacidades a menudo tienen muchas obligaciones adicionales relacionadas con el cuidado de sus hijos. Hay citas con el doctor, citas con terapeutas y juntas adicionales cada ciclo escolar con los maestros y el personal de apoyo en la escuela de sus hijos. Algunos papás pueden encontrarse justo en el límite de lo que puedan manejar. Algunas familias pueden haber experimentado el rechazo de su comunidad de fe y creen que el programa parroquial de formación en la fe no podrá o no querrá acomodar las necesidades de sus hijos. [4] Los niños con discapacidades deben de ser incluidos en todos los programas católicos para la formación en la fe. Para lograr su incorporación, es cuestión de crear comunidades cristianas incluyentes que den la bienvenida a los niños con discapacidades y a sus familias.

Inclusive Children's Religious Formation: Three Parts, One Community

In 2005, the United States Conference of Catholic Bishops published The National Directory for Catechesis, which states, “each person with a disability has catechetical needs that the Christian community must recognize and meet. All baptized persons with disabilities have a right to adequate catechesis and deserve the means to develop a relationship with God.”[1] My interest and involvement in the religious formation of children with disabilities has its roots in personal experience. As I searched for answers about what was best for our family, I found that our story was common; and though some students are being catechized at home, students absent from their parish faith formation programs are missing a fundamental element of the Christian faith: community.

Where are the Children with Disabilities?

Like most parents, I never imagined my child would need special education. My husband and I had a dream and a goal to educate our children in Catholic schools for grades K-12. When our fifth child, Grace, entered kindergarten that dream began to crumble. I knew, from her first day, Grace would need extra help staying seated, lining up, and waiting her turn. What I didn’t realize was that her lack of eye contact, inability to remember the names of extended family, and obsession with dinosaurs were indicators of an Autism Spectrum Disorder, a diagnosis we would not receive until the summer after her kindergarten year. Gracie’s deficits in communication skills were seen as disrespect, her lack of social skills as unkindness towards classmates, and her sensory sensitivities as immature, even wild behavior. My husband and I made the decision then to let go of our dream, and Grace joined the 13 percent of students who receive special education services in public school.[2] We knew that we needed to provide our child with her faith formation; we chose to home school in the beginning. For three years we taught Grace and prepared her for First Reconciliation and First Communion using our parish faith formation program materials.

Public school students comprise the majority of the children who attend Catholic faith formation programs. If 13% of children in public school receive special education services, it would be fair to assume that 13 % (1 in every 8) of the students in faith formation programs require some kind of educational support to optimize their learning outcomes. John Paul II defined the optimal learning outcome for religious education: “The definitive aim of catechesis is to put people not only in touch, but also in communion and intimacy, with Jesus Christ…”[3] In the Catholic tradition, this also includes the preparation and reception of the Sacraments of Reconciliation, Eucharist, and Confirmation.

The numbers of students with disabilities in our faith formation programs do not match the statistics. Parents may be withholding information about their children’s needs or not enrolling them at all. The reasons for this vary. Parents of children with disabilities often have many additional obligations in the care of their children. There are medical appointments, therapy appointments, and additional meetings each school year with teachers and support staff at the child’s school. Some parents may just be at the limit of what they can manage. Some families may have already experienced rejection from their faith community and believe that their parish faith formation program cannot or will not accommodate their child’s needs.[4] Children with disabilities must be included in Catholic faith formation programs. Getting them there is a matter of creating inclusive Christian communities that will welcome children with disabilities and their families.

More than in the Movies: Introducing Consecrated Religious Life to a New Generation

“Mom, what’s that?” a little girl in the grocery store unabashedly asked as I walked past them in the produce aisle. Slightly embarrassed at her daughter’s rather loud and candid question, her mother simply and timidly responded “She’s a lady who loves Jesus.” I smiled at both mother and daughter and gave a little wave as I kept on in pursuit of the items on my list. In living my call to consecrated religious life over the past thirteen years, there have been plenty of experiences similar to this and I am sure that every sister has a supply of her own. Humorous as they may be, still they point to a sad reality that consecrated religious life is not as visible or fostered as it was in decades past and that the simplistic answer may have been the extent of that mother’s knowledge of the reality of this state in life. There was a time when most young people were exposed to sisters in the classroom, parish, or even in the family, but those days are gone. Most knowledge of religious life comes rather from movies like “The Sound of Music” or “Sister Act,” but the life of consecration has a depth and beauty worth studying and sharing with a generation that tends to long for more and settle for less. Throughout Salvation History, God has called men and women to follow him in the consecrated life. They have borne witness to the Gospel by living heaven on earth. In this way, they have revealed the providence of God in every age through their trust and their loving service to their brothers and sisters in need. From the earliest days, God called individuals to himself, as with the desert fathers, but that expression of single-hearted following of Christ eventually flowered into individuals living a dedicated life in community. Founders and foundresses responded to the needs of each particular time and established religious institutes within which members consecrated themselves to God through vowing the Evangelical Counsels, living in community, and serving according to their particular situation in apostolates such as health care, education, and care for the poor and needy of every condition. God’s call goes forth even today inviting young people to forsake the promises of the world for the sake of embracing his eternal promises. Vowing to live poverty, chastity, and obedience in a world that exalts material goods, sexual license, and individualism is counter-cultural to say the least, but it is a path worth discerning and a journey worth taking. Catechists have a particular role to play in assisting young people to encounter the truth and beauty of a call to be consecrated to God through the profession of the evangelical counsels through education and exposure. While the General Directory for Catechesis instructs that “every means should be used to encourage vocations to the priesthood, and to the different forms of consecration to God in religious and apostolic life and to awaken special missionary vocations,”[1] it is essential to remember that God is the source of every vocation. The role of the catechist is to propose to students that such a particular vocation is not just in the movies and that there is a real possibility that they could be called and ought to learn to listen to the gentle voice of the Good Shepherd.

Children's Catechesis—Vocations: Helping Children and Teens Hear God's Call

We often ask children various versions of the same question: “What do you want to be when you grow up?” “What kind of job would you like to have?” Career days at elementary schools are built around this question. When I was in the sixth grade, we were assigned to investigate various careers and do a report about one we might like to pursue. I initially chose “psychologist,” but my father, who wasn’t a big fan of psychology, encouraged me to think of something else. I did my report on forensic pathology. (Spoiler alert: I became a psychologist anyway!)

As Catholics and disciples, what we want to be is only a piece of what we need to consider when thinking about our life’s path. A more relevant question is, “What is God’s plan for your life? What does he want you to be?” It seems that even many Catholic parents, teachers, and catechists are hesitant to ask this question. Perhaps we worry that it’s too much pressure to ask it this way. Many parents say they just want their kids “to be happy.” But we often don’t know what will make us happy. We search for happiness in all the wrong places: material possessions, status, power, and unhealthy relationships. In contrast, true and lasting happiness is found only in living the lives we were created to live. When we discover something new that we really enjoy, we often say, “I was made for this.” That’s because we are at our best, and often experiencing our greatest joy, when we are doing what we were made for. It’s time we start asking our young people, not only what they want to do, but what God has made them for.

For many kids and teens (and even some adults), there is no easy answer to this question. With a few exceptions in salvation history, God doesn’t usually speak in an audible voice and tell us what to do. Perhaps this is because of his profound respect for our free will. We might not feel like we had much choice if God audibly directed our most important decisions. Also, we tend to value things a little more if we have to work for them. If we have invested time and energy into our search for a purpose, we will be more engaged in that purpose when we find it. A third reason God might not tell us directly about his plan for our lives is that he delights in taking us on a “treasure hunt.” Some parents, on birthdays or Christmas, hide gifts in various places around the house and provide clues for their kids to find them. These parents talk about how exciting this makes the experience of opening the gifts and how much fun it is to see their children find what they have hidden. God is our Father. We are his children. And parents delight in those times when their kids find something they have hidden just for them.

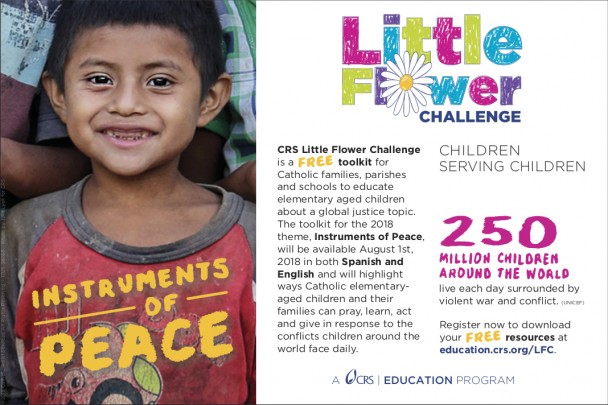

AD: Catholic Relief Services Little Flower Challenge Tool Kit for Families & Schools

Register now to download your resources at education.crs.org/LFC.

Children's Catechesis: Keeping it REAL in Catechesis

It would certainly be less work to use plastic beads for sorting in Montessori school or use battery operated candles to minimize clean up. However, the artificial does not hold the same attraction for young children as the real.

In our catechetical work, whatever methods we use, we may be tempted to avoid the real because it’s messy, risky, uncomfortable, expensive, and requires more work. Our parish youth minister does an activity with teens using lighted candles to remember babies whose lives were ended by abortion. The first year, the parish maintenance staff was more than a little displeased by the extra work involved in cleaning wax from the floor. The next year our youth minister considered using battery operated candles, but his team agreed that the symbol of the living flame being snuffed out is more powerful with a real candle; so, although it took more time and effort, they devised ways to keep the candles from dripping on the floor.

Real is Beautiful

We all find the real more beautiful than the artificial. Who does not prefer the glow of candlelight to other forms of lighting? A fine linen napkin is more beautiful than the best paper product, and silk flowers are only attractive in as much as they approximate the blooms they imitate.

In remarks to artists, Pope Benedict XVI connects reality and beauty: “the experience of beauty does not remove us from reality; on the contrary, it leads to a direct encounter with the daily reality of our lives, liberating it from darkness, transfiguring it, making it radiant and beautiful.”[i] In the remainder of this article we explore some practical ways catechists can honor the orientation of the human person toward reality.

The Spiritual Life: A Eucharistic Spirituality for the Family

Perhaps it would be an understatement to say that today much confusion surrounds the understanding of marriage and the family. This is certainly the case in the secular world; although from the experience of the two-year Synod on the family, it would appear that Catholics (clergy and laity alike) are not immune from the confusion. The reasons for this are too many to name for a short article. Rather, I would prefer to propose a solution, one that is both simple and challenging. The answer to the challenges of marriage and the family is holiness in the domestic church. This is actually good news for it places the responsibility for solving these problems outside of our reach since holiness, properly speaking, belongs to God alone (cf. Mk 10:18).

A Vision of Education for Catholic Schools

Recently, a highly gifted colleague of mine told me of a visit she had made to officials of a nearby diocesan school system. This lady is an outstanding educational practitioner with very high quality skills in special and gifted educational strategies. The visit had gone very well, and the school authorities were very interested in what she was offering on behalf of the university. Yet there was one part of the visit that perplexed her. She had been asked this question: What is the difference between what you are offering as a Catholic university and what is available through the nearby public university? The lady is a very committed and faithful Catholic, but she felt a little ill at ease and unable to articulate the difference. So she asked me about it. This was not an attempt on her part to have a glib answer to offer. She was genuinely interested in what changes might be made to the actual work that she does. Actually, I was delighted to be asked. It is something that has occupied me for over thirty years and lay at the core of my own doctoral thesis. In this article, I intend to offer an overarching vision of the Catholic educational project.

Seeing with Both Eyes

The great Australian theologian, Frank Sheed, once wrote a book with the puzzling title Theology and Sanity. What does theology have to do with sanity? Everything! The classic definition of truth from St. Thomas Aquinas is: “Veritas est adaequatio rei et intellectus.”[i] To put that in layman’s terms, St. Thomas claims that we have the truth when what we have in our minds conforms to what really exists. In Sheed’s view, to see things as they really are is to be “sane” and by contrast, when a person genuinely believes in a world view that is not true, that person is “insane.” For this reason, Catholic teachers must teach differently from their public school counterparts, presenting reality as it is by incorporating both natural and supernatural perspectives. Pope John Paul II famously insisted that the human person ascends to God on two wings “faith and reason.” There are some educational systems that view reality from the perspective of faith alone: fideism; others insist on excluding whatever cannot be measured and observed: rationalism. Neither of these perspectives can properly express a Catholic vision of education. Chesterton put it rather more colorfully by reminding us that human sight is stereoscopic: to view anything with only one eye is to see it wrongly.