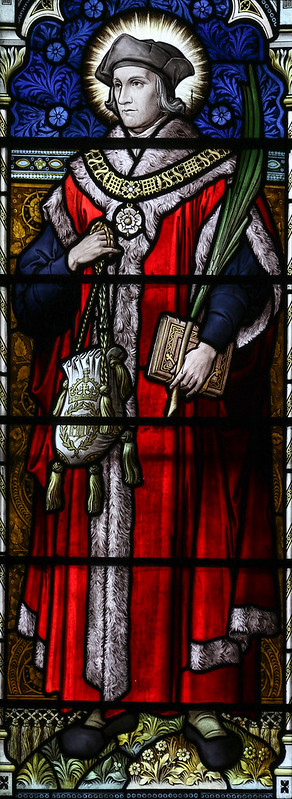

Sitting alone in his prison cell in the Tower of London, awaiting his execution, Sir Thomas More wrote a prayer in the margins of his prayer book. “Give me thy grace, good Lord, to set the world at naught; to set my mind fast upon thee, and not to hang upon the blast of men’s mouths.”[1] In the minds of many throughout Europe in 1535, Sir Thomas had already heroically set his earthly good (and goods) to the side in his refusal to take the Oath of Supremacy to King Henry VIII. This intimate glimpse into his interior life reveals how, during his darkest hours, he prayed for final perseverance in choosing the good.

Are saints born good? Or, for some, does the gift of God’s grace make the pursuit of virtue easy? Many lives of the saints we may have read as children (or watched on the screen) might have us think so. We rarely catch in these depictions the struggle for virtue. In the life and writings of St. Thomas More, we can learn much.

In those final days, Thomas also prays, “Almighty God, have mercy…on all that bear me evil will and would harm me.” Certainly, such a prayer is admirable to us, reflecting the final words of our Lord from the Cross. Thomas then takes it further: “And by such easy, tender, and merciful means as your infinite wisdom can best devise, grant that their faults and mine may both be amended and redressed; and make us saved souls in heaven together, where we may ever live and love together with You and Your blessed saints.”

Acknowledging his own need for mercy and correction, he asks God to do the same for those intending him evil, so that together with his enemies he might enjoy eternal life with God and the saints. This is Thomas’ prayer amidst injustice and vitriol, knowing that his enemies will bring suffering and great loss to himself and to his family. He ends this prayer with words that reveal how he is able to hope for this: “The things, good Lord, that I pray for, give me the grace to labor for.[2]

St. Thomas More shows us that the achievement of virtue in life is both divine gift and the fruit of our persistent labor. The Church describes human virtue as “a habitual and firm disposition to do the good” (CCC 1803). A virtue is habitual, meaning we make it such a repeated act that we don’t need to deliberate or struggle as much to choose it. Think here of any virtuous habit: daily physical exercise (certainly the most socially exalted of the virtuous practices), prayer every morning, or the regular practice of honesty. A virtue is also a firm disposition to do the good. By its regular practice, it has become steady and strong.

A consistent, developed disposition to do the good: this is exactly what we want to form in those we teach. In addition to teaching the Ten Commandments, the Beatitudes, and the theological and human virtues, something else is needed. The Catechism tells us that our catechesis must also “cause one to grasp the beauty and attraction of right dispositions towards goodness” (CCC 1697). That is, we must also help our students see the “attractiveness” of morally good actions, so that they might be drawn to the good. There are two ways in particular that will help us in this task.

First, we can help them make room in their minds for what Philippians 4:8 prescribes, because thinking about certain things is a necessary life habit for a follower of Jesus. “Whatever is true, whatever is honorable, whatever is just, whatever is pure, whatever is lovely, whatever is gracious, if there is any excellence and if there is anything worthy of praise, think about these things.” Our virtuous actions flow directly from what we think about; and so we must fill our minds with the right things.

Second, we must introduce them to the lives of virtuous contemporary men and women and to the lives of the saints, especially to help them see the struggles and rewards of a life of virtue.

We live in an era where the “blasts from men’s mouths” (and women’s too!) dominate the consciousness of many, bringing much fear and anxiety. We catechists must be little lights in the darkness, especially for those we teach. And we will bring light as we (like St. Thomas More) learn to set our minds fast upon the Lord, giving prominent space in our thoughts to whatever is true, honorable, just, pure, lovely, and gracious. Doing so in these difficult times is just what those around us need.

Dr. James Pauley is Professor of Theology and Catechetics at Franciscan University of Steubenville and author of the new book, An Evangelizing Catechesis: Teaching from Your Encounter with Christ (Our Sunday Visitor, August 2020).

Notes

[1] Gerard B. Wegemer, Thomas More: A Portrait of Courage (Princeton, NJ: Scepter Publishers, 1995), 191.

[2] Ibid., 219.

This article is from The Catechetical Review (Online Edition ISSN 2379-6324) and may be copied for catechetical purposes only. It may not be reprinted in another published work without the permission of The Catechetical Review by contacting [email protected]