The Way and Witness of a Holy Marriage

The matrimony of two of the baptized…is in real, essential and intrinsic relationship with the mystery of the union of Christ with the church…it participates in its nature…marriage is deeply seated and rooted therefore in the Eucharistic mystery.[1]

This spiritual vision of marriage, as articulated by Cardinal Caffara, may appear as novel or even bizarre or “cultist” to many younger members of western culture. The defining characteristic for marriage today is that it has no defining characteristic. It is open and runny and borderless. We decide what marriage is, and hence it has devolved from a sacrament to a “private love.” This “love’s” very meaning is malleable, and its connection to procreation and permanence and the divine is severed. Yet for the Catholic Church, marriage is still the primordial mystery, one which reveals God’s love for humanity. This revelation has been consistent from the beginning of the Bible all the way through to the Bridegroom, Christ, giving himself completely upon the cross for the Bride, the Church (Is 62:5; Hos 2:18-20; Jer 3:20; Ez 15:8-15; Mt 22:1-14; 9:14; 22:1-2; 25:1; Eph 5:32). Marriage reveals that God’s own love is free, faithful, forever covenanted, and always life giving. Deep within the suffering of giving and receiving one another in married love God himself is becoming known to the couple. One cannot live such free self-giving in a permanent life-giving way without glimpsing God even in traces, by those, too, who believe marriage is permanent but not a sacrament. For God’s very nature is love, and all true love seeks to freely self-donate in a permanent life-giving way.

Marriage: An Ongoing Encounter with Christ

For the committed Catholic couple, marriage’s true nature has been revealed specifically in the life, death, and resurrection of Christ. And it is into this mystery of Jesus’ own spousal love that all Catholic couples are taken when they consent in Christ to love one another until the end. There is no private meaning to spousal love for Catholic couples as their love transcends themselves from its very beginning. As a sacrament, marriage is an ongoing encounter with the power of Christ’s own life and love. Each couple abides with Christ and is empowered to love through the Holy Spirit. With such a Spirit the couple loves each other with Christ’s own love (CCC 1661).

The cultural and political understanding of marriage as private love is far from this dynamic and sacred understanding of marriage as loving with Christ’s own love. Ending a more superficial and self-defining notion of marriage will only occur through one powerful reality: the witness of Catholic couples who drink deeply of the mystical vision of marriage. By “mystical” I don’t mean a marriage filled with disembodied voices, levitations, or meditative trances. Mystical marriages are grounded in the mysteries of Christ, and these mysteries are communicated most normally and powerfully at the Eucharistic Liturgy. In other words, to live a mystical marriage, which invites the culture to consider a more profound and transcendent understanding of marital love, a couple needs to receive their own marital life from the Eucharist. To have the Eucharist fuel a couple’s love for one another is to be “mystical.”

AD: Family Catechesis Program

This is a paid advertisement in the July-September 2019 issue. Advertisements should not be viewed as endorsements from the publisher. To learn more about this Family Catechesis Program click here or call 763-757-1148.

Children's Catechesis: Faith Formation—It’s Not Just for Kids

Parable of the Paper Cups

Once upon a time, there was a village called “Ville de Soif.” Ville de Soif was located along a river, which was the water source for the whole town. At various times, people came to the river to drink, using their hands. But they didn’t seem to have a way to take water with them when they left. The adults in town busied themselves with work and other activities, but stayed thirsty between their visits to the river.

The children of the village spent more time at the river. They frequently visited with an elder of the village who lived right on the riverbank, a rare adult who was not thirsty all the time. He taught the children how to make origami cups out of paper. The children were excited to have something that could hold water, but when they tried to take water home to their parents, it seemed the paper cups just weren’t strong enough to last. So the adults continued to thirst, and the children continued to get only just a little more water than their parents. It seemed the town was doomed to be chronically thirsty.

As far-fetched as this story might seem, this is exactly the situation we face in adult faith formation in the Church in the United States today. Our culture desperately thirsts for meaning, direction, value, and justice, but the distractions of daily life keep many from going to the source. For those who do come, often the children, we do our best to offer something to satisfy their thirst, but it’s never quite enough, and the “paper cups” our catechists teach them to make often don’t even reach their homes in one piece.

And so our culture continues to thirst: for meaning, for direction, for value, for justice. Our society has become increasingly polarized and unkind. We have forgotten how to dialogue with one another. Our Catholic faith offers us a roadmap for renewing our own lives and the culture around us, but we must drink freely of the living water Jesus offers us before we can share it with others.

How can we get more adults involved in forming their faith, becoming intentional disciples, and thus renewing their families, our parishes, and the world in which we live? Here are some tips for helping parents and other adults form their faith.

Adult Faith Formation in the Hispanic Catholic Community in the United States: A Reflection

“Evangelization is the fundamental mission of the Church. It is also an ongoing process of encountering Christ, a process that Hispanic Catholics have taken to heart in their pastoral planning. This process generates a mística (mystical theology) and a spirituality that lead to conversion, communion, and solidarity, touching every dimension of Christian life and transforming every human situation.”[1]

On the occasion of this important milestone marking the publication of the USCCB’s seminal document on adult faith formation, Our Hearts Were Burning Within Us (hereafter “the document”), issued on the cusp of the new millennium, it is worth reflecting on its impact and influence on Hispanic ministry in this country. Much has taken place since that time, while significant ongoing challenges remain.

Some Pertinent Principles

Although the document does not explicitly address the Hispanic or other specific cultural communities, a number of its organizing principles do speak to some noteworthy realities. These principles will be the touchstones for this reflection. First, persons will always prefer to worship where they feel comfortable and at home. Second, faith as it relates to the family is a critical factor in any religious tradition. And lastly, social customs and popular devotion in harmony with the Gospel are to be respected, affirmed, and celebrated.

First Things First - Welcoming and Hospitality

While data are generally lacking regarding the number of Hispanics who have left the Catholic Church, current information suggests that a significant number of Hispanics who were baptized as Catholics join other Christian denominations and religious traditions every year; including fundamentalist groups and “storefront” churches—many of which maintain Hispanic cultural traditions that might otherwise be considered to be “Catholic,” including quinceañeras (fifteenth birthday blessings) and Epiphany celebrations. New arrivals often find the structure of the parish and the style of worship to be very different from what they experienced in their native country. In this unfamiliar environment, they are frequently targeted for what could be considered aggressive proselytizing by non-Catholic groups, and are offered transportation, many kinds of assistance, skillful scriptural preaching, as well as a friendly community to which to belong.

All this highlights the compelling need for Catholic parishes to provide a welcoming and hospitable atmosphere to newcomers, including Spanish-language and/or bilingual worship, ministries, parish pastoral leaders, and personnel whenever possible. In addition, Catholic parishes must be aware of several factors that can make Hispanics feel unwelcomed in the Catholic Church and make them more open to seeking a home in other faith traditions. Among these factors are: an unspoken attitude from parish staff or parishioners that they are “undesirable”; excessive or overwhelming administrative rules and forms; and being required to produce evidence of contribution envelopes before they can receive the sacraments.[2]

Como ayudar a los niños y a sus familias a vivir los Sacramentos de la Penitencia y Reconciliación y de la Eucaristía

Children's Catechesis: Helping Children & Families Live the Sacraments of Penance & Eucharist

The Catechism of the Catholic Church calls the sacraments, “the masterworks of God in the new and everlasting covenant” (1116). The sacraments confer upon us a special grace that assists us in becoming the people God created us to be. Unfortunately, too often the first celebration of the sacraments in childhood is approached as if it were a one-time developmental milestone, rather than the beginning of a lifelong celebration or a further step down the path of continuing conversion.

Both experience and research have shown us that the period of preparation for the Sacraments of Penance and Eucharist is a rare time when even families who are only marginally connected to the parish are willing to spend more time in formation. This can be an opportunity for evangelization, if catechists and catechetical leaders are open to the Holy Spirit and focus their catechesis not only on preparation for the initial reception of the sacraments but also on the ways in which the sacraments can change our lives.

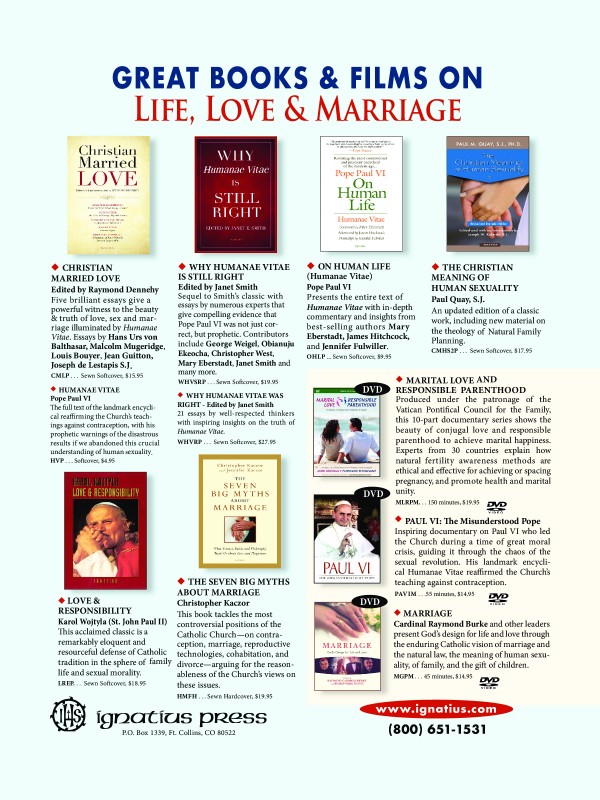

AD: Great Books & Films on Life, Love & Marriage from Ignatius Press

This is a paid advertisement. To view more books from Ignatius Press click here, or call (800)651-1531.

Children's Catechesis: Forming a Culture of Prayer within the Home

What do you remember of your first day of Grade One? My memory gave prophetic purpose and life-long value to my life! After taking roll and assigning seats to her 120 students (not a typographical error!), petite Sister St. Rose announced that our first lesson would be the most important lesson of our lives. She distributed our first catechism book and directed us to lesson one. With pencil in hand, we circled question numbers one, two, and three. Sister instructed us in the meaning of the words and told us to have our parents teach us how to say the words with our eyes closed. My mother proctored homework time. She amazed me when, without looking at the book, she knew the answers to the three questions. More amazing yet was dinner conversation that night. Mom said, “Pat, tell dad what you learned at school today.” I looked my dad straight in the eye and declared with conviction, “I learned why God made me.” Without skipping a beat my father proclaimed, “Pat, God made you to know him, to love him, and to serve him in this world, and to be happy with him forever in the next.” Dad’s reply had an exponential influence because he had justly earned the nickname of “Daddy Old Bad Boy.” Dad’s misbehaviors were legendary and yearly Santa Claus deposited coal in his stocking because of it. So, when this man knew why God made me, I embraced the belief hook, line, and sinker! Echoing the sentiment of Robert Frost1, “that has made all the difference.” Coming to know God—and growing in that knowledge and experience over time—is our universal call, our primary vocation. Knowledge of God and the ways of God leads to love. A person who does not love God does not know God! And whenever any of us love another person we can’t help but overflow into service for them. Prayer: Both Action and Attitude As “First Heralds of the Gospel”2 parents bear the privilege and the responsibility to introduce their children to God; to sensitize them to recognize the ways of God; to learn how to speak to God; to distinguish God’s voice and will from other voices; and to respond to God in age-appropriate ways. Prayer is the common thread for these goals. What is prayer? Definitions abound. Even Wikipedia weighs in on the topic. My core definition, and one that I offer to contemporary parents, comes from that same first grade catechism: “Prayer is the lifting of our minds and hearts to God.” Prayer can be vocal or mental, formal or informal, private or corporate, scheduled or spontaneous. Prayer changes through the ages and stages of one’s life, just as the quality and style of communication changes over time between persons who are growing in relationship. Prayer is communication with the One who knows us better than we know ourselves and Who loves us beyond our ability to comprehend such love. Consistently God communicates God’s love and life-giving will, though we are frequently unaware or inattentive. Often the busyness of life blocks recognition of God’s movements. The noises of our environment drown out the whispers of God’s love. Regardless of our awareness, God continues to speak, to reach out, and to offer friendship. Prayer is both an action and an attitude. Any person, place, stimulus, or event that lifts our minds and hearts to God can be a catalyst of prayer. Spiritual practices that are understood and faithfully embraced raise our spiritual consciousness. Environments, customs, and rituals that tutor the soul or recall God’s presence can stir holy desire and affection.

Desde los Pastores: Una catequesis de pertenencia

El papel de la familia como modelo catequético para el ministerio hispano

From the Shepherds: A Catechesis of Belonging

The Role of the Family as the Catechetical Model for Hispanic Ministry

To read this article in Spanish, click here.