Inspired Through Art — The Wheel and the Rod

To view a full resolution of this artwork on a smartboard, click here.

Any first impression of The Procession to Calvary by Pieter Bruegel the Elder is telling. I can still remember my initial encounter with it. The scene came across as a chaotic, dizzying whirlwind of activity. Beyond the larger mourning figures in the foreground, I felt a deeper disturbance in the picture, the source of which remained unknown. It seemed to reverberate through the crowd that thronged the landscape, like ripples pushing through the water after a stone has been thrown in.

The sheer number of figures was overwhelming. I wasn’t sure where to look. What were they all doing? There were people milling around in a field, men on horseback, farmers hauling their goods toward the town. I saw a traveler resting with his giant pack, while nearby a man was being arrested. A woman tried to intervene as others scattered with their belongings. I observed the crowd staring at the commotion, the figures turning a blind eye, and still others completely oblivious, going about their daily business. In the background, children play. None of these vignettes, however, seemed to be what this painting was about.

Then it struck me: at the epicenter of the painting was the diminutive personage of Christ, hidden in plain sight, fallen under the weight of the collective sin of mankind. I could hear the crack as he hit the ground. Just behind him, the gaping jaws of the earth opened to swallow all things. This is The Procession to Calvary, the Via Crucis!

A sort of dispersing flow led my gaze to the distant hilltop where the men would be crucified. Encircling the site was a crowd. Among the bystanders, the first Christians gathered as a community around the sacrifice of our Lord. By an ingenious trick of pictorial composition (the similarity in shape), my eye was compelled to jump to the wagon wheel. Following the shaft downward, I arrived at a mound littered with bones: Golgotha.

Here Pieter Bruegel the Elder transports us in a vision to the remote foot of the Cross. We see women weep and pray as St. John consoles our Lady. A thistle, a symbol of original sin, grows in this darkened corner of the world. As viewers, we are both at the periphery and the center of this event—both/and. The name given to this place comes from the Hebrew noun גלגלת (gulgoleth, “skull” or “head”). A skull is prominently displayed; Christ is the head. It is also related to the verb גלל (galal, “to roll”). This rolling action is a key to unlocking the structures and patterns at work in this composition and, by extension, in this event.

Ask, Seek, Knock: The Pitfalls and Potential of Catholic Door-to-Door Evangelization

“He’s just too small,” sobbed a woman we had just met. It was a sunny summer day, and the pastor, transitional deacon, and I were out knocking on doors within our parish boundaries. This woman’s door was within eyesight of the rectory, and it happened to be the first one we had visited. The conversation had started off just as awkwardly as one would imagine. She answered the door hesitantly, but smiled as we introduced ourselves. She was a parishioner and relaxed when she saw the pastor standing at the back of our group. We explained that we were out introducing ourselves and the parish to the neighborhood. When we asked if there were any intentions we could pray for, she took a deep breath and said yes. She then began to tell us about her unborn grandson and how her daughter’s pregnancy was not going well. She asked us to pray for the baby boy, who was just too small.

“He’s just too small,” sobbed a woman we had just met. It was a sunny summer day, and the pastor, transitional deacon, and I were out knocking on doors within our parish boundaries. This woman’s door was within eyesight of the rectory, and it happened to be the first one we had visited. The conversation had started off just as awkwardly as one would imagine. She answered the door hesitantly, but smiled as we introduced ourselves. She was a parishioner and relaxed when she saw the pastor standing at the back of our group. We explained that we were out introducing ourselves and the parish to the neighborhood. When we asked if there were any intentions we could pray for, she took a deep breath and said yes. She then began to tell us about her unborn grandson and how her daughter’s pregnancy was not going well. She asked us to pray for the baby boy, who was just too small.

We could have just as easily not been there. That same morning, I had offered a training for any parishioners who wanted to learn about door-to-door evangelization. The idea was to walk them through a basic script at the parish and let them shadow those of us with more experience as we knocked on doors in the surrounding neighborhood. Nobody came.

Door-to-door ministry is a frightening prospect for many Catholics, and it is a frightening ministry to organize. Yet, there are overflowing graces to be had, both for the evangelist and the evangelized. Consider my opening story: What would have been lost if our team had gone home after the failed training seminar? Within eyesight of our parish was someone who needed Jesus’ comfort and the only way we could bring it to her was by following Christ’s own counsel: “Ask, . . . seek, . . . knock” (Mt 7:7).

I have been engaged in door-to-door evangelization since 2017. In that time, I have knocked on countless doors and said countless prayers. I have been invited into living rooms and have been cursed from behind locked doors. I have interrupted drug deals and witnessed spontaneous neighborhood prayer meetings. Through it all, I have become convinced that this style of ministry does have a place in the Catholic Church.

Historically, door-to-door ministry has been the near-exclusive province of Protestants, Latter Day Saints, and Jehovah’s Witnesses. Frankly, there have been times that, after seeing two men in white dress shirts and ties walking through my neighborhood, I suddenly decided there were errands I needed to run. Undoubtedly, the first pitfall to be overcome in this ministry is its perception. The very words “door-to-door” conjure up images of tract-wielding zealots and vacuum cleaner salesmen. The only way to change this perception is to do the ministry a different way. What if door-to-door evangelists were like those servants of the master who went out into the streets and through the city inviting all they met to the great wedding feast (see Lk 14:15–24)?

Missionary Worship

There is an interesting phenomenon that occurs in nearly every culture across history: man ritualizes worship. All over the world the similarities are astounding—animal sacrifices, burnt offerings, gifts of grain, the joy of ecstatic praise. It points to a universal sense within man that not only recognizes that there is a God but also knows that man is called to represent the created order before the Creator. This universal orientation toward the divine can help us recognize what it means to become Eucharistic missionaries.

There is an interesting phenomenon that occurs in nearly every culture across history: man ritualizes worship. All over the world the similarities are astounding—animal sacrifices, burnt offerings, gifts of grain, the joy of ecstatic praise. It points to a universal sense within man that not only recognizes that there is a God but also knows that man is called to represent the created order before the Creator. This universal orientation toward the divine can help us recognize what it means to become Eucharistic missionaries.

A Little World

Man is similar to the dust of the earth, the plants that grow, and the animals that move and feel. Yet, he isn’t confined to a “fixed pattern” like the plants and animals; rather, he has been given “the privilege of freedom” like the angels.[1] He is a “little world” arranged in harmonious order in which matter is given voice, elevated, and ennobled by its participation in man’s freely offered “spiritual worship” (Rom 12:1).[2] He has a deep capacity to entrust himself. Standing at the summit and center of creation, he is capable of free obedience to God, which allows for the transformation of his life into a living liturgy of praise.

As matter and spirit, man is also capable of seeing beyond. In the novella A River Runs Through It, an expert fisherman shares his thought process for recognizing a good fishing hole: “All there is to thinking is seeing something noticeable which makes you see something you weren’t noticing which makes you see something that isn’t even visible.”[3] Looking again and again until one sees the “something that isn’t even visible” is a recognition that the world is sacramental, a world of signs, permeated and ordered by Wisdom. Man comes to see that this world is a gift “destined for and addressed to man” (CCC 299). As anyone knows, the reception of a gift elicits first wonder and delight and then gratitude and praise as we lift our eyes from the gift to the giver. A sacramental view of the world moves man to lift his eyes to the Giver and, on behalf of the entire cosmos, to “offer all creation back to him” in a sacrifice of thanksgiving (CCC 358).[4]

Watered Garden

In the biblical account it is this worship that brings order; or rather, worship is the locus of right order. As a little world, man sums up all things, so when he entrusts himself into the hands of God, he gives everything. This gives his worship an inherently outward dimension—it includes more than himself. When man worships, everything worships, and so everything is consecrated. In the garden, rivers ran through it and out to the whole earth (Gn 2:10–14), making it a paradise in which the first Adam “played with childlike freedom.”[5] One can see here a created echo, a sort of natural catechesis, of Eternal Wisdom playing before the Father like a little child, “rejoicing before him always, rejoicing in his inhabited world” (Prv 8:30–31).

Editor's Reflections— The Eucharistic Congress and the Missionary Year

Catholics in the United States have a long history of hosting both national and international Eucharistic congresses. The first of these was in Washington, DC, in 1895, and the last was in Philadelphia in 1976. If your ancestors were Catholic and lived in North America, they may have participated in one of these congresses—in St. Louis (1901), or New York (1904), or New Orleans (1938), or another of the 11 congresses to date. I’ve been thinking lately about the congress that took place in Cleveland in 1935. My grandparents were in the area at that time, and as believing Catholics it’s a good bet that they went to this congress and that it was a profound experience for them. These congresses—spanning across generations, and for many of us across our family histories—have been catalysts of faith and have played an important role in the Catholic history of the United States.

In 1987, I was able to see both St. John Paul II and St. Teresa of Calcutta in person in Phoenix. I’ve also gone to two World Youth Days (in 1993 and 2000). I will never forget these large events and how they have shaped me. Of course, this is to be expected, since the visible gathering of many Catholics around Jesus in the Eucharist expresses in a unique way the Mystical Body of Christ and is truly a foretaste of heaven. On my two pilgrimages to World Youth Day, we had long bus rides after the closing Mass. Using the bus microphones, teenager after teenager gave powerful testimony to how they experienced the goodness and the love of God and how they wanted to live in a new way.

While the United States has hosted Eucharistic congresses before, this is the first year that a walking Eucharistic procession across the country has been planned. And there are four of these—taking place right now! These walking pilgrimages are roughly forming a cross shape of blessing over our country. This is one way that we Catholics are asking the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit to bless and transform our country. There is much national discussion these days about the diminishment of Catholic faith in our current cultural circumstances. The walking pilgrimages and the Eucharistic Congress are tangible ways we can step forward and publicly express our love for Jesus in the Eucharist and our love for the Catholic faith. And such a public profession will strengthen our faith—and the faith of others, too. If there is any possible way you can participate in the pilgrimages or the congress in Indianapolis from July 17–21, it is (perhaps) a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to bear witness to Jesus in a way that will have tremendous evangelistic power in our broader society.

AD: Recharge & Reconnect — Summer 2024 Steubenville Conferences

To learn more or to register for a Steubenville Youth or Adult Conference visit https://steubenvilleconferences.com/ or call 740-283-6315.

OCIA & Adult Faith Formation — Adult Evangelization and Catechesis: Today’s Great Need

Back in 1989, when I first began working as a parish catechetical leader, I remember becoming alert to a pattern that unfolded regularly in our church parking lot. Two nights a week, our empty parking lot would become quite busy for two short periods of time. A line of cars would begin to form at 6:45 p.m. that would slowly inch along as parents dropped their children and teens off for parish catechesis. Then the lot emptied except for the dozen or so cars of the catechists. And then, an hour and a half later, the methodical line would predictably form again and creep along as parents retrieved their kids.

I had never been particularly attentive to this until that night. My alertness came about because of a contrasting pattern I had noticed for the first time in a church down the street. The previous week, I had noticed just how different the experience was in the evangelical Christian church parking lot. On Tuesdays, Wednesdays, and Thursdays, that church also had many cars entering the lot. But these cars were parked and remained for several hours until their drivers exited together at around 9 p.m. In that community, the adult drivers got out of their cars and entered, and then, surprisingly, remained in the building. As their kids went to Bible studies, so did their parents and other adults; whereas in our Catholic parish, the adult-chauffeurs immediately departed as their kids were catechized. In one church, the idea of studying and growing in an understanding of God’s Word was normative adult Christian life. Yet in the other—in ours—catechesis was an activity meant for the kids.

When it comes to the Catholic parishes with which each of us might be most familiar, what age level receives the most focused catechetical attention?

Servant of God Nicholas Black Elk: Native American Catechist

Many moons ago, when I was a young social work student in North Dakota, I was required to take a course called “Indian Studies.” One of the books for the course was titled Black Elk Speaks.

Many moons ago, when I was a young social work student in North Dakota, I was required to take a course called “Indian Studies.” One of the books for the course was titled Black Elk Speaks.

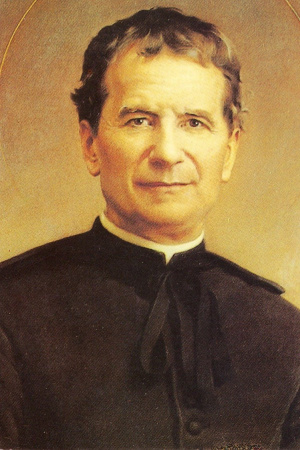

From the Shepherds — Learning From the Charism of St. John Bosco

In the Latin language there is a saying that could also be applied to our work as catechists: nomen est omen. This means that the name also reflects the inner essence of a person or a thing. In other words, the name speaks for itself. The name of St.

In the Latin language there is a saying that could also be applied to our work as catechists: nomen est omen. This means that the name also reflects the inner essence of a person or a thing. In other words, the name speaks for itself. The name of St.

Building Ministry Bridges: The Advantages of Collaboration in Youth Ministry

When my sixteen-year-old son was young I asked him, as people do with young children, what he wanted to do when he grew up. His response was that he wanted to build bridges in the sky. I was not exactly sure what he meant by that, but I certainly look forward to how it turns out. Building bridges is a meaningful and significant undertaking. Bridges occupy the space between us and help bring people together. Clearly, I am not speaking solely of physical bridges. I am not so sure my son was, either.

The word “collaborate” means “to work jointly with others in some endeavor.”[1] The “labor” part in the word clearly means work, but I found the first part of the word to be interesting. The prefix “col” is from the French word for a pass or depression in a mountain range. If you have ever driven through the Brenner Pass in the Tyrolian Alps, you know that, like bridges, passes bring people together.

When we collaborate, we participate in the work of the Holy Spirit: the work of unity. We take part in fulfilling the prayer of Jesus in the Garden of Gethsemane: “I do not ask for these only, but also for those who will believe in me through their word, that they may all be one, just as you, Father, are in me, and I in you, that they also may be in us, so that the world may believe that you have sent me” (Jn 17:20–21). When we seek unity with others through our ministry, we mirror the inner workings of the Holy Trinity, which is an unending, perfectly collaborative relationship.

So, how do we use our ministries to construct bridges? What does it look like for us to “fill the spaces” that separate us from others in the labor of evangelization? What valleys are we willing to traverse to bring people together? How do we carry out youth ministry in a collaborative way that successfully allows us to include and impact those we may not otherwise accompany? Let us explore a handful of ecclesial bodies in which we could labor to increase collaboration.

Thank God for Pain

How much worse off we would all be without physical pain! As counterintuitive as it sounds, pain is your friend. Pain is a mechanism to warn you that something is wrong. Imagine a scenario where there was no physical pain. When you get sick with a virus, you don’t feel bad, so you don’t take care of yourself. The virus spreads rapidly because there is no way to know that you have it until it is too late. Death or relentless monitoring become the only two ways to know that something is physically awry. Who would want to live like that? Dramatically shortened lifespans and constant paranoia? No thanks!

Twenty years ago, when I was first diagnosed with cancer, it was pain that made me go see a doctor. Thank goodness the pain arrived in time! The doctors found the cancer and treated it before it was too late. I’ve received 20 additional years on this good earth because of this good friend, pain. If it weren’t for pain, I wouldn’t be alive to write this today. I am grateful!

Because it is so familiar, physical pain is no longer very intimidating to me. Of course I don’t like it, but it’s manageable. Besides alerting me to something being amiss, it is helpful because it is purifying. It calls me to something higher. For instance, when a tech comes into my hospital room to wake me up in the middle of the night to draw blood, I am challenged to respond with kindness and docility. She appears abruptly with a bright light and sharp needle to do her job. This is rather unpleasant for me, but it’s also for my good. The least I can do is be pleasant to her regardless of how I am feeling. Subtle sighs or groans of annoyance or self-pity only serve to assault her with an air of needless negativity. What good does that do? I admit that sometimes I fail, but the pain offers me a great opportunity. It calls me to become the best version of myself.