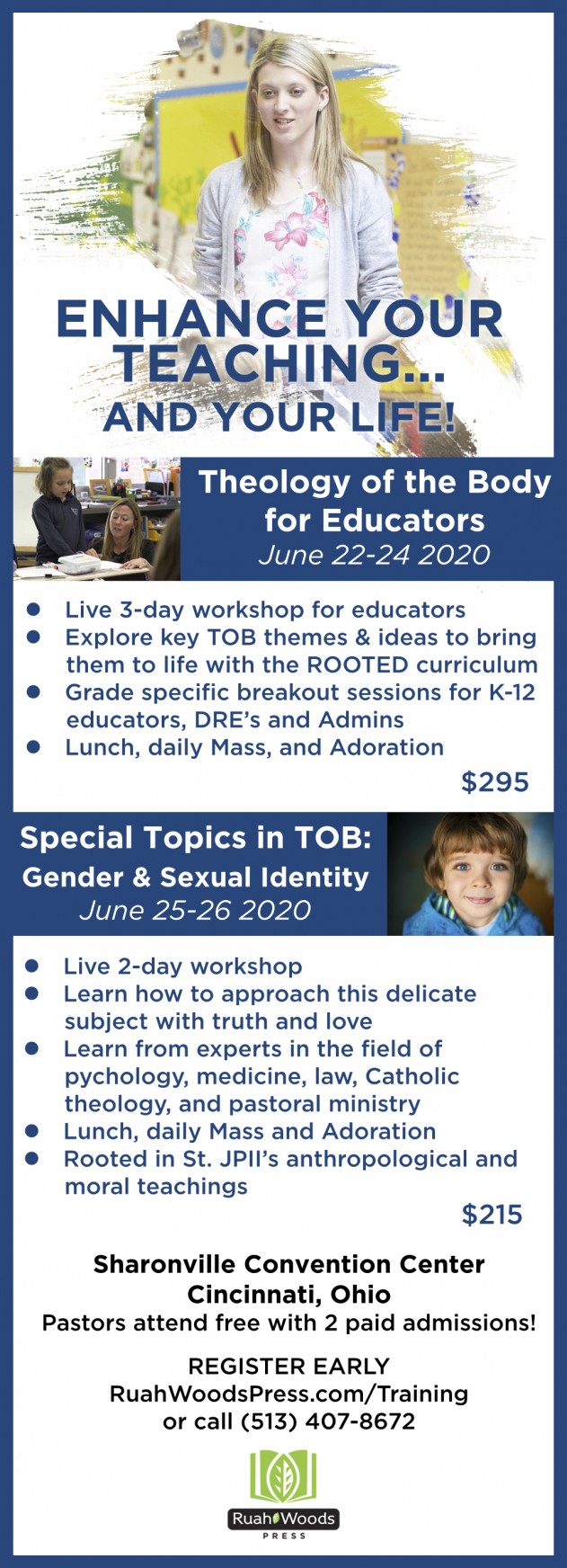

AD: Theology of the Body June 2020 Conferences

To register or to get more information about the Theology of the Body June 2020 Conferences, visit RuahWoodsPress.com/Training or call (513) 407-8672.

This is a paid advertisement and should not be considered an endorsement from the publisher.

Madeleine Delbrêl: The Missionary and the Church

By the time Venerable Madeleine Delbrêl was 20, she had converted to Catholicism from the strict atheism of her youth. Nine years later, in 1933, she was living as a missionary with two companions in Ivry, “the first Communist city and more or less the capital of Communism in France.” She decided to live in this community because she remembered the pain of not knowing God; her goal was not simply to evangelize them, but to befriend them. She lived there until she died in 1964.

Venerable Madeleine Delbrêl had an exceptional love for the Church and perceived that there was a profound link between Christ, the Church, and evangelization. “The work of the Church is the salvation of the world; the world cannot not be saved except by the Church.” In our current atmosphere of skepticism towards structures of authority and of the Church herself, she is a voice that reminds us how to love the Church, and how to bring Christ to the world in and through her.

Madeleine considered each person in the Church to be an essential part of the Church’s mission; there was no one who did not have a part to play. “We are not the Church unless we are the whole Church: each member belongs to the whole body.” Each person’s part was specific and vital: “And we are not the whole Church unless we are in precisely the place meant for us in the Church, which is the same as saying that we are precisely in our place in the world, where the Church is made present through us.”

These words are comforting and hopeful, but we always seem to struggle to find our purpose and direction. Delbrêl’s view is that we do not have to go crazy finding exotic projects: “Mission means doing the very work of Christ wherever we happen to be. We will not be the Church and salvation will not reach the ends of the earth unless we help save the people in the very situations in which we live.” These situations, these people where we live, have been entrusted to us. When we don’t take this mission seriously, the world suffers.

Her words profoundly challenge me. I am often dreaming of my next “important project,” but fail to see the people and the situations that are very truly before my eyes.

The Spiritual Life: Fasting – My Personal Experience

In December of 2009, I was hospitalized for four days in two different hospitals with a blood platelet crisis. Platelets cause your blood to clot when necessary and I didn’t have enough of them (ITP). I had been fighting 3 separate occurrences of cancer since 2003, and while the cancer was no longer present, the treatments (including two stem cell transplants) had been so brutal that I was constantly in the hospital for something.

This particular hospitalization occurred the week before Christmas and came on the heels of a deep inner darkness, a time of great difficulty both spiritually and emotionally. However strange as it might sound from the outside, I found this stint in the hospital to be a great blessing. Having spent many long periods of time in hospitals, I am at home in them. This four-day period became a sort of retreat for me where the darkness lifted and I felt renewed in body, mind, and spirit.

Just a couple days before Christmas, I was released from the University of Chicago Medical Center. My wife drove me back to our home in South Bend in the afternoon. That evening I needed to go to the drug store to get the five prescriptions that awaited me. I was feeling well enough to drive and, frankly, I wanted to experience some autonomy and independence so despite my weakened condition, I decided to go and get them myself.

While I was waiting in line, I noticed a short little Christian book on fasting which seemed like it was jumping out from the stand in the waiting area. (Yes, in Indiana you can still find Christian books in drug stores.) If books could talk, this book was shouting at me! As I browsed through it, I saw that it laid out biblical reasons for fasting and included testimonies about how fruitful the practice of fasting has been in the life of this pastor-author and his congregation. Longing desperately for more fruit in my own life, I purchased it and spent most of the night reading it. The next day, I drove to a local convent’s Eucharistic Adoration chapel and finished reading it, using the Scripture citations in the book to look up and read all the passages directly myself. As I studied them, I could feel my heart burning.

Now it’s not like I’ve never fasted. Fasting was a part of my “re-version” twenty years previous as a young college graduate. But I was a different person then, much more youthful, naïve, and prone to excessive enthusiasm. As my Christian conversion deepened and moved from a lot of emotion toward a more lasting and quiet commitment, I encountered a Catholic Church which seemed rather unenthusiastic about fasting. Except when I was around people who had gone on pilgrimages to Medjugorje, whenever the topic came up, the topic of fasting was usually met with so many warnings and calls for prudence, moderation, and caution that it seemed like fasting was something the Church actually wanted to discourage. My impression was that in the eyes of most Catholics, fasting was really something only for zealots and extremists. To even bring up the topic made people look at you funny. Well, I didn’t want to be a zealot or an extremist, so I avoided fasting altogether, except during Lent when it was “safe” or perhaps secretly for special occasions. I pursued other “safer” routes towards closeness with Christ.

This little book from the drug store rekindled some long smoldering embers. It pointed me towards the biblical basis for fasting. I was familiar with many of the biblical stories, but it was like the scales were falling off my eyes and I began to notice things that I have never noticed. During the ensuing month, I spent many hours in that convent chapel reading and praying about fasting, as I sat in the presence Jesus in the Blessed Sacrament.

Then a couple weeks later, I had a conversation with a devout Catholic doctor friend about the spiritual practice of fasting. I wanted to make sure that it would not hurt my health to fast as I had made a commitment to my wife that I would always do what the doctors recommended. (This promise was to alleviate her stress about her husband having cancer.) As anyone with medical issues should do, I asked him if I could fast. He replied that nobody had ever asked him that. He requested that I give him a little time to read and think about it, and I said, “Of course.” Then only a day or two later, he emailed me some material that actually encouraged the practice of fasting from a physiological point of view. I was surprised but excited as I really wanted to begin as soon as possible. This was the green light I needed to overcome my fear of being a zealot and a fool, a great step forward towards the practice of fasting for me.

RCIA & Adult Faith Formation: Mystagogy that Unveils the Mystery of the Church

It happens more than we like to admit: after a joy-filled Easter Vigil, many new Catholics skip out on the post-baptismal catechesis sessions. Our best plans for a riveting exploration of the rich theological and historical meaning of the sacred signs of our faith serve only a few.

Like other RCIA directors, this trend in my own parish has given me much cause for reflection. Was it something I did or didn’t do? There may be any number of reasons why someone does not attend mystagogy, but there are also good reasons why people do show up. Last year, our sessions after Easter were better attended and more appreciated than in years past, due to some changes that helped. This article will share with you a few observations and ideas from that experience.

“Fear not little flock”- Luke 12:22

To begin, we started our RCIA with a smaller group than usual. This, of course, was not a freely chosen change! While I, and the RCIA team, mourned the lower numbers and searched for any reasons for it, we soon discovered something important. This smaller group of people (about 10 candidates and catechumens plus their sponsors) bonded with each other seemingly better than any of our other groups before. The retreats and minor rites also went better. There was simply more time to devote to each person, and more impetus for each one to get to know the others. The friendships that formed among the catechumens and candidates helped inspire the improved attendance of mystagogy, I’m sure. Call it positive peer pressure.

Other little changes also helped improved attendance. For example, during the Lenten season, we mentioned mystagogy at almost every turn. It was presented as something important and exciting that we looked forward to doing with them. Part of the reason we could be so positive involves the new elements we included. I will speak of those later.

In battling the business of everyone’s schedule, we conceded a few things to the rhythm of the secular calendar. For example, on Mothers’ Day and Fathers’ Day, we did not ask them to participate in a mystagogical session apart from attending the Mass of their choice. They appreciated the break and the time with their families.

When we gathered together to unpack the sacraments, the sacred signs, and their layers of significance, the sessions were heavily driven by discussion. They each had an opportunity to speak about what was most meaningful to them in each sacrament. This was a welcomed change in rhythm from our more didactic catechumenal sessions on the sacraments. At times, their insights were amazing! One young man shared his experience of “being made totally new” by Jesus in Holy Communion.

Finally, when the concluding celebration of mystagogy took place on Pentecost, to help encourage attendance, we included a special thank you brunch prepared by the new Catholics for their sponsors. No one wanted to miss it!

Altogether, having a smaller group who got along well together was the first of several changes that God made during our RCIA last year. Sensitivity to family and more dialogical catechetical sessions helped to reinvigorate our RCIA process. However, there was still one more change that we made last year, which everyone appreciated: we discovered and engaged our local Church community (beyond our parish), experiencing the joys of warm hospitality and service.

El acompañamiento en la verdad y en la caridad: el camino a la libertad auténtica

Talladas en piedra arriba del portal de entrada al patio de la institución educativa fundacional de nuestra Congregación se encuentran las palabras (en latín por un lado y en inglés por el otro): dar a conocer la verdad es la caridad más grande. Durante los seis años en que impartía clases en aquella escuela, no ignoraba que esta fuera una declaración controvertida en nuestro mundo actual. Cuando pensamos en la caridad, pensamos en actos realizados para servir a los pobres, como las obras corporales de misericordia. Si pensamos en la caridad en cuanto al habla, muchos la asocian con actitudes y palabras de tolerancia que eviten toda confrontación. Sin embargo, me atrevo a afirmar que poca gente piensa espontáneamente que la verdad y la caridad son por necesidad vinculadas. Pero, éste es central al mensaje y a la Persona misma de Jesucristo, Quien enseñó no solamente que Dios es Amor (1 Jn 4,8), sino que Él, como Dios Encarnado, es el Camino, la Verdad, y la Vida (Jn 14,6).

Podemos preguntarnos porqué la verdad ha caído en desprestigio. Va más allá del alcance y los límites de este artículo explorar en profundidad los efectos de la Ilustración que han llevado a algunos a dudar si la verdad siquiera existe, especialmente en cuanto a los conocibles bienes éticos universales. Dado que este artículo pretende abordar el enfoque pastoral sobre la verdad, merece que nos tomemos el tiempo para explorar algunas razones al nivel de la aplicación por las que la gente pueda percibir cierto divorcio entre la verdad y la caridad.

Retos al matrimonio de la verdad y la caridad

Rembrandt's painting of The Return of the Prodigal Son¿Por qué dar a conocer la verdad es una de las formas (si no la forma) más altas de la caridad? Jesús dijo, “Conocerán la verdad y la verdad los hará libres” (Jn 8,32). Son pocas las personas que disputarían el hecho de que hoy en día todos queremos ser libres, pero puesto que la libertad a menudo se ha interpretado como licencia para elegir entre todas las alternativas posibles, sin importar el impacto que tenga sobre sí mismo y sobre las demás personas, debemos de reexaminar la libertad en sí a la luz de la verdad.

Teológicamente hablando, podemos afirmar que el don de la libertad se nos da de parte de nuestro Creador Quien nos hizo en Su imagen, capaces de conocer la verdad de lo que es bueno, y, por lo tanto, capaces también de elegir lo que es bueno, eligiendo, en último término, amar. Según el gran tomista, Servais Pinckaers, el énfasis excesivo que pone el voluntarista sobre la voluntad resultó en una noción de “libertad para la indiferencia” que es meramente la capacidad de elegir entre dos contrarios que proceden únicamente de la voluntad.[1] Desde esta perspectiva, cada elección es independiente, sin ningún fin unificador a la vista. La ley no solamente es externa a nuestra libertad, sino que también limita nuestra libertad por medio de obligaciones impuestas desde afuera.

Accompaniment in Truth and Charity: The Path to Authentic Freedom

Carved in stone above the courtyard entry to our Congregation’s founding educational institution are the words (in Latin on one side and English on the other): to give truth is the greatest charity. For the six years I taught at that school, it was not lost on me that this is a radical and controversial statement in our world today. When we think of charity, we think of acts done to serve the poor, such as the corporal works of mercy. If we think of charity in speech, many associate this with attitudes and words of non-confrontational tolerance. But I dare to say that few people spontaneously think of truth and charity as necessarily linked. Yet this is central to the message and the very Person of Jesus Christ, who not only taught that God is love (1 Jn 4:8), but that he, as God incarnate, is the way, the truth, and the life (Jn 14:6).

We might ask why truth has fallen into disrepute. It goes beyond the scope and limits of this article to explore in depth the effects of the Enlightenment that have led some to doubt whether there even is truth, especially concerning knowable universal ethical goods. Because this article aims to address the pastoral approach to the truth, it seems worth our time to explore a few reasons at the applied level that people perceive a divorce between truth and charity.

Challenges to Wedding Truth and Charity

Why is giving truth one of (if not the) highest forms of charity? Jesus said, “You shall know the truth and the truth shall set you free” (Jn 8:32). Few would argue against the fact that today we all want to be free, but because freedom has often been interpreted as the license to choose among all possible alternatives, regardless of the impact on the person and on others, freedom itself needs to be revisited in the light of truth.

Theologically we can say that the gift of freedom is given to us by our Creator who made us in his own image, capable of knowing the truth of what is good and therefore of choosing what is good, ultimately choosing to love. According to the great Thomist Servais Pinckaers, the voluntarist overemphasis on the will resulted in a concept of “freedom of indifference” that is merely the ability to choose between two contraries proceeding from the will alone.[1] From this perspective, each choice is independent, with no unifying end in view. Law is not only external to our freedom, but it also limits our freedom through obligation imposed from outside.

Leisure: The Basis of Renewal

Two Thinkers, One Counterintuitive Approach

Evangelizing structures change. They must and they do. The Second Vatican Council emphasizes that the Church’s very nature is missionary and that she exists to reveal the mystery of Jesus Christ in every generation.[1] In order for evangelization to be fruitfully carried out in any age, the Church must employ human strategies, or “manmade” evangelizing structures suited to the communication of the Gospel within the present circumstances. A cursory glance at the Church’s history reveals a variety of such structures: the preaching of the Fathers and the sacrifice of the martyrs in the early Church, the emergence of monastic and mendicant movements during the Middle Ages, the explosion of religious congregations following the Reformation, the growth of Catholic schools, and so forth. Many of these elements are still in place, though their prominence in the Church’s overall evangelizing movement shifts based upon the needs of the time.

Given culture’s constant flux, the Church’s evangelizing mechanisms can become ineffective or obsolete and, therefore, in need of updating. If these structures are not renewed, they risk obscuring the Church’s ability to communicate Christ clearly. Moreover, without renewal, the Church can tend to devolve into an entity concerned more with self-reference, self-preservation, and maintenance than with actualizing her missional nature as the sacrament of salvation pointing to Another—the one who spends herself with Christ for the salvation of souls. Therefore, the effectiveness of the Church’s mission in every age is, in some sense, contingent upon constant ecclesial renewal, the constant renewal of her evangelizing structures.

Vatican II’s call for aggiornamento is essential for a New Evangelization that is “new in its ardor, methods and expression.”[2] That renewal is necessary is not the question following the Council, the real debate has to do with precisely how one ought to go about renewing methods and structures. This little article is not the space for a complete treatment of the various approaches to renewal that spun out of the Council and into the decades that immediately followed it. Instead, I will attempt to offer a few insights regarding an approach to renewal that appears in the thought of Joseph Ratzinger, and make a few connections to the teaching of Joseph Pieper, a 20th century German philosopher, and his treatment of the concept of leisure. Ultimately, something quite surprising emerges in the thought of these men, namely, that the source of renewal does not lie in activity or work but—perhaps counterintuitively—in the effortlessness of leisure and the surprise of faith.

Leisure in the Life of the Christian

The first time I read Josef Pieper’s book Leisure: The Basis of Culture, I felt I had finally encountered the philosophical and theological categories to explain the discomfort I felt in a culture obsessed with nonstop activity, imagery, and noise. Perhaps also being a first-generation American, with a Middle Eastern sensibility of leisure, I felt especially out of place.

Unfortunately, it seems modern Christians have long abandoned the primacy of leisure, its foundation in the life of prayer and holiness, and, which Josef Pieper so brilliantly explains, its necessity in the restoration of a desirable culture.

The Meaning of Leisure

Leisure is not a thing to be done, it is a way to be. It is, for that reason, somewhat difficult to define. Pieper describes it as a “mental and spiritual attitude, a condition of the soul, an inward calm, of silence, of not being ‘busy’ and letting things happen.”[2]

Therefore, the definition of leisure is much richer than merely being on vacation, having fun, entertaining oneself or doing “leisurely” activities. These things are often done for the sake of the rest needed to return to work. Leisure is not for the sake of work, it’s not for the sake of anything!

The loss of leisure, both personally and culturally, is not only the loss of the dignity and value of the person but also of the human personality.

The Meaning of Christianity

The Christian faith is precisely that—faith. It is the recognition of a presence, a loving presence, in one’s life. It is a recognition of a spiritual reality beyond the practical reality of the world of work. It is an entrance into a loving relationship with the Presence, who has revealed himself to man in the Person of the God-man Jesus Christ. For the person who has truly encountered him, denying this relationship would be unreasonable. Like all personal relationships, it takes work, but not the sort of work the world values. It takes another kind of work.

Two Conceptions of Work

The work it takes to know God, in other words, to be in a relationship with him, is quite different than the work the world values. The sort of work the world values is the kind that is difficult and effortful. This understanding of work originates, according to Pieper, with a “father” of modern philosophy, Immanuel Kant.

For Kant, even intellectual work has to be exclusively discursive. It consists essentially in the act of “comparing, examining, relating, distinguishing, abstracting, deducing, demonstrating—all of which are forms of active intellectual effort."[3] Therefore, the work of knowing is activity, and it is this characteristic of activity that justifies intellectual work and makes it credible.

However, this interpretation of the act of knowing, of intellectual work, is not the only one. The ancient Greek and Medieval philosophers believed that the discursive use of the intellect (ratio/reason) is only one way of knowing. The other way of knowing is through the intuition (simplex intuitus/simply looking). Pieper explains the distinction by using the example of knowing a rose. A rose can be known discursively by taking it apart, observing it, studying it, and, therefore in a sense, "possessing" it.[4] Or it can be known by simply gazing upon and absorbing its beauty. The defining characteristic of the intuition is receptivity, rather than activity.

For the ancients and later the Christians, the work of knowing involves both the activity of reason and the receptivity of intuition.

Prayer is the Work of the Christian

An elevated knowledge of God comes through the receptivity of intuition rather than through discursive reasoning. Pieper writes, “the highest form of knowledge comes to man like a gift—the sudden illumination, a stroke of genius, true contemplation; it comes effortlessly and without trouble.”[5]

Lydia, a girl in my youth group, once told me: “I’m really looking forward to it.” When I asked her what she’s looking forward to, she replied, “I don’t know exactly but it’s exciting!” The awareness Lydia had of her desire for the infinite, her poverty of spirit, is what leisure cultivates in the human person. It has been said that true prayer is simply waiting for God to come when and how he wants. However, it is not a passive waiting, but a receptive one.

Yet, without the silence, space, and time for the cultivation of leisure, I cannot pray well. I cannot wait well. And then I may not be in a prime position to recognize “when and how” he arrives. If life is too busy (especially dangerous if it is busy with “pious” and “churchy” activities), then even time set aside for prayer becomes burdensome and moralistic. If I am uncomfortable with silence (both interior and exterior), then I am neither comfortable with myself nor God and others. When this discomfort becomes habitual, it is the vice of sloth.

Sloth is the Enemy of Leisure

Sloth (or acedĭa) is contrary to leisure; because, while leisure is an openness to reality, sloth is a habitual sorrow in front of reality and specifically spiritual reality. This sadness is so oppressive that the person who suffers from sloth “wants to do nothing” and experiences a “sluggishness of the mind.”[6] Slothful people are idle, restless, agitated, and often workaholics. They are spiritually lazy and easily bored. The worst form of sloth is despair, which is ultimately “a refusal to be oneself.”[7]

Even a superficial reflection of the current cultural crises makes evident enough that this “refusal to be oneself” characterizes the present moment. Consider the staggering opioid crisis and sky-rocketing rates of youth suicide as two examples among the many.

El espíritu católico del descanso

Introducción

Cuando le comenté a mi esposa que estaba escribiendo un ensayo acerca del descanso, se suscitó el siguiente diálogo:

Esposa -No lo puedes hacer.-

Yo -¿Por qué no?-

Esposa -No sabes nada acerca de eso. Estás siempre trabajando en algo.-

Yo -Hay algo de cierto en lo que dices, pero el descanso no trata precisamente de lo que se hace cuando uno no está trabajando. Básicamente, es una actitud hacia la vida.-

Este es el punto principal: el descanso, correctamente comprendido, es una perspectiva que tenemos en cuanto al sentido de la vida y el vivirla de forma consecuente. Tal perspectiva, o espíritu, debería de fundamentar y unificar toda nuestra manera de ser. Para el cristiano, el verdadero Espíritu de la vida es Cristo. Cuando nuestro día consiste en el buen trabajo, bien ordenado e imbuido por Él, la vida debe y puede convertirse en una peregrinación personal que fluye de forma personal desde Él y vuelve hacia Él

El tema de la naturaleza y el papel del descanso es, por lo consiguiente, tema importante. De hecho, le ha intrigado y, a veces, consumido al hombre a lo largo de la historia, y con buena razón. Porque todos compartimos la necesidad de contestar a la pregunta eterna, “¿Qué debemos de hacer para obtener la felicidad?” La respuesta se relaciona de manera directa con la necesidad innata que tiene el ser humano de comprender la relación correcta entre lo espiritual y lo material; la obligación humana de discernir la naturaleza de la felicidad y los medios apropiados que debemos de buscar para asegurarla. La resolución propuesta, y el papel que tiene el descanso, varía mucho, como lo atestiguan las religiones del mundo, los grandes pensadores y las culturas que los acompañan.

Para el cristiano, la felicidad se encuentra en La Encarnación. Dios se hizo hombre para que el hombre pudiera regresar a Dios. Pero, ¿cómo le hacemos para aceptar la promesa y la invitación que nos da Dios para liberarnos de modo que podamos regresar a Él? Debemos de servirle santa y rectamente: santamente en el sentido de que debemos amar a Dios y valorar los dones espirituales de la fe y de la razón, y rectamente en el sentido de que debemos ordenar nuestro día con un esfuerzo honrado por vivir una vida buena y honrosa. Porque tenemos que recordar que, sin Dios, en vano trabajamos, sin importar cuán sagaces y diligentes hemos sido al desempeñar nuestras labores cotidianas. Dicho sencillamente, el descanso no es el tiempo que disfrutamos tras terminar nuestro deber de ganarnos la vida. En lugar de eso, el descanso en verdad debería de ser ese tiempo especial que tomamos para discernir y reflexionar sobre el qué y el porqué de lo que deberíamos de estar haciendo en todos los aspectos de nuestra vida. Al permitirle a Dios que se encarne en toda nuestra forma de ser, podemos vivir una vida católica de descanso porque Él “guiará nuestros pasos por el camino de la paz”.

Sí, ciertamente es una enorme tarea, ya que el espíritu del catolicismo de descanso involucra a la totalidad de la vocación cristiana. Pero, lo único que queremos hacer aquí es volver a considerar nuevamente algunos de los aspectos fundamentales y prácticos del estilo de vida del cristiano, y hacerlo a pesar de las exigencias de nuestra sociedad moderna. Abordemos este proyecto como obra en tres partes. Primero, ratifica para ti mismo lo que constituye el espíritu cristiano de la vida, y el papel del descanso y del trabajo implícitos en ello. En segundo lugar, vuelve a considerar e implementar algunas destrezas diarias que ayudarán a incorporar y ordenar tu vida y tu trabajo. En tercer lugar, dale mayor vigor al sentido cristiano de la vida, viéndola como una peregrinación personal hacia Dios. Esta perspectiva y enfoque integral enriquecerá tu propia felicidad, y, a su vez, avivará tu llamado de amar y de guiar aquellas personas que están bajo tu cuidado.

The Spirit of Leisurely Catholicism

When I happened to mention to my wife that I was writing an essay about leisure, the following dialogue took place: Wife: “You can’t do that.” Me: “Why not?” Wife: “You don’t know anything about it. You’re working at something all the time.” Me: “That is somewhat true, but leisure isn’t really about what one does when one is not working. It’s fundamentally an attitude toward life.” That is the main point: leisure, properly understood, is a perspective one holds regarding both the meaning of life and the ensuing way of living it. Such a perspective, or spirit, should inform and unify one’s entire way of being. For the Christian, the true Spirit of life is Christ. When our day consists in good ordered work imbued by him, life should and can become a personal pilgrimage that flows peacefully from and back to him.

The subject of the nature and role of leisure in life is therefore an important one. In fact, it has intrigued and at times consumed man throughout history, and this for good reason. For we all share the need to answer the following timeless question: “What must one do in order to gain happiness?” The answer is directly associated with man’s inherent need to understand the proper relationship between the spiritual and the material; the human obligation to discern the nature of happiness and the appropriate means we should seek to secure it. The proposed resolution, and the role of leisure in it, varies greatly, as the world’s religions, great thinkers and attendant cultures bear witness.

For the Christian, happiness is found in The Incarnation. God became man so that man might return to God. But how do we accept God’s promise and invitation to be set free by him so that we can return to him? We must serve him in a holy and righteous manner: holy in the sense that we must love God and value the spiritual gifts of faith and reason, and righteous in the sense that we order our day in an honest effort to live a good and honorable life. For we must remember that without God, we labor in vain, no matter how astute and assiduous our daily endeavors. Simply stated, leisure is not the time we enjoy after our duty of making a living is done. Rather, leisure really should be that special time we take to discern and reflect upon why and what we should be doing in all aspects of our life. As we allow God to incarnate our entire way of being, we can live a leisurely Catholic life because he “will guide our feet into the way of peace.”

Yes, this is a tall order, for the spirit of leisurely Catholicism entails the totality of the Christian vocation. But all we want to do here is to reconsider afresh some of the fundamental and practical aspects of the Christian way of life, and do so despite the demands of our modern society. Let’s approach this venture as a three-part endeavor. First, reaffirm for yourself what constitutes the Christian spirit of life, and the role of leisure and work implicitly entailed within it. Second, reconsider and implement some practical daily skills that will help embody and order your life and work. Third, invigorate the Christian meaning of life by seeing it as a personal pilgrimage to God. This overall perspective and approach will enrich your own true happiness and, in turn, enliven your calling to love and to guide those within your care.