Click here to view artwork on smart board.

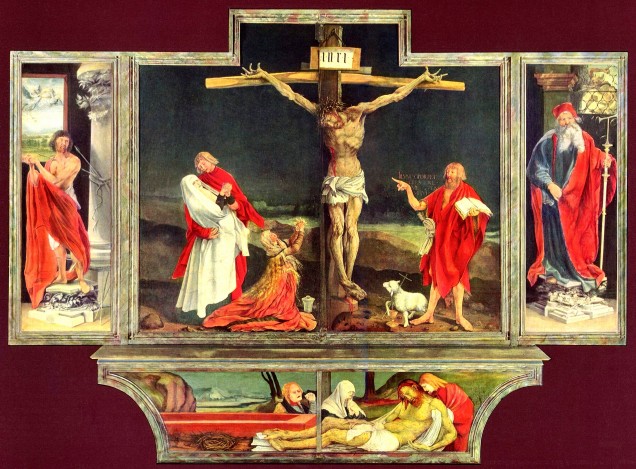

There are few scenes of the crucified Christ that convey the emotion seen in the center panel of the Isenheim Altarpiece. But emotion is simply the beginning of this sorrowful depiction of Jesus on the Cross; the multi-paneled altarpiece was and is an invitation to journey with Christ in a narrative that concludes in hope.

Matthias Grunewald’s altarpiece was created for the Monastery of St. Anthony in Isenheim, Germany around the year 1512. It is a polyptych: a set of images hinged in such a way as to be a visual catechism able to be set in various configurations. Multiple saints appear in the panels, especially St. Anthony of the Desert, one of the hermits who established lives of asceticism in the Egyptian desert in the 4th century. Among its numerous panels, there are many signature elements of visual design that place it in the realm of Northern Renaissance image-making. These include a focused attention on intimate details, exaggerations of form and proportions, and a mystical sense—portraying supernatural experiences outside of natural time and space.

St. Anthony’s Fire

The deep mystery of salvific suffering is embedded in this image in a unique way. At the Monastery of St. Anthony, the Antonine monks became well-known for their care of individuals suffering from a condition that was known as “St. Anthony’s Fire.” This affliction was caused by ergotism: a fungal infection that could permeate a patient’s body, causing skin lesions that often led to gangrenous limbs and eventually death. The true cause of ergotism was only to be discovered centuries later when scientists found that the fungus begins its life cycle in rye grain, and then is consumed in food products. The mysterious appearance of these afflictions would cause one to think of a supernatural cause. The monks would treat the patients with great care, developing remedies both physical and spiritual. Their acts of mercy were a devoted response to the patronage of St. Anthony and his perseverance during his harrowing torments by demons in the desert.

The altarpiece was designed to help these suffering patients understand that they were not alone. Grunewald accomplished that by creating the image of Jesus suffering as these patients did themselves—with sores and lesions covering his tortured body. In doing so, Grunewald gives to us a vision of Jesus unlike any other—one which we may contemplate as we suffer, either with daily frustrations or a debilitating condition caused by illness or infirmity. If we look at the body of Jesus from part to part, we can see more than just open sores and discoloration of skin. Let’s focus on a few examples:

Grunewald depicts the expired Jesus with hands frozen in writhing pain.

Grunewald depicts the expired Jesus with hands frozen in writhing pain.- Jesus’ torso is emaciated and distorted.

- Jesus’ feet show not only the effect of torture and piercing, but also the withering effect of St. Anthony’s Fire, which disfigures the extremities in just such a manner.

How well this image confirms reality! Jesus, out of ultimate and perfect love, not only took on our human nature but also became like the lowliest of us—those who suffer. There is an eternal and particular aspect of intimacy between the suffering Jesus and the suffering human. This altarpiece helped the patients at the monastery draw closer to Christ, and it can help us as well. Jesus knows what it is like to be like us.

In the image, we see that Grunewald makes the body of Jesus larger than the other figures. This hierarchical relationship is intended to make us focus on him as most important in the scene. Mary, His Mother, and St. John the Beloved are present as we would expect, reacting to the horror of the Crucifixion. Often made present at the foot of the Cross, we see Mary Magdalen in anguish. Also made present, outside of time, is St. John the Baptist pointing to Jesus. Here Grunewald paints in Latin text from John 3:30 in the Vulgate of St. Jerome. It reads: illum oportet crescere me autem minui. Translated, John is saying: “He must increase, but I must decrease.” We also remember that as the last Prophet, he proclaims in John 1:29, “…Behold! The Lamb of God who takes away the sin of the world!” In the image, this is reinforced by the inclusion of the lamb and the small cross in the crook of its leg. Blood pours out of the lamb’s side into a chalice on the ground. These visual elements are fused together in the Eucharistic mystery: the Sacrifice on Calvary and the Sacrifice of the Mass are a unity.

By including St. John the Baptist with Christ and Mary, the iconographic form of a deësis is suggested. The Greek word deësis means “prayer,” or “supplication.” This compositional form was most usually found in the Eastern Church as a Last Judgment image of John and Mary interceding at the heavenly throne. However, this visual arrangement was included in other works of the Northern Renaissance, notably the Ghent Altarpiece of Hubert and Jan Van Eyck. By using this form here, and by bringing John the Baptist to Calvary, Grunewald bends time and suggests an eschatological theme. Time may be flexible in image-making; but truly, it is also inevitable—we will meet Christ and we will intimately experience the foot of the Cross at the Judgment Seat. We can look at this image and imagine hearing: “…this is what I gave you…what did you give me?”

Christ Our Hope

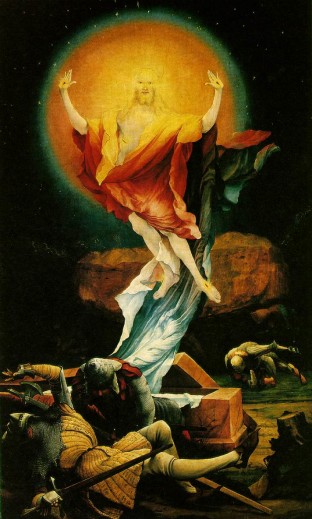

For those who join themselves to Christ, we must remember: there is more than suffering. Grunewald didn’t forget this. While additional parts of the altarpiece depict other scenes of grief and of St. Anthony’s torments, the outer wings can be opened to show that Grunewald included scenes of the Annunciation, as well as Mary and the Child Jesus in elaborate decorative settings. Then finally, with an image that defies naturalism, he depicts the Resurrection in the most powerful terms. This Christ is not walking out of the tomb; he is arising into a cosmic aureole of golden light. This mystical vision of the Resurrection is unique. A hundred years ahead of the Baroque, it relies on that later era’s dramatic power of light and darkness. However, anticipating the artists of even later centuries, the primary hues of blue, red, and yellow are a resounding and intensely colorful chord of joy in the glory of hope—hope that we are invited to share as we contemplate our own meeting with Christ in glory to come.

Long before the spectacle of digital media and IMAX theatres, an image such as the Isenheim Altarpiece provided an otherworldly experience that must have shaken the viewers to the root of their souls. As we contemplate this image and its purpose, we can learn how the active love of the Antonine monks at work in their monastery and the active Catholic mind of Grunewald creating this altarpiece both exemplify the awakened heart transformed by grace.

Linus Meldrum is an Assistant Professor of Fine Arts at Franciscan University where he teaches the core curriculum course, Visual Arts and the Catholic Imagination, as well as Studio Art.

This article was originally on pages 21-24 of the printed edition.

This article is from The Catechetical Review (Online Edition ISSN 2379-6324) and may be copied for catechetical purposes only. It may not be reprinted in another published work without the permission of The Catechetical Review by contacting [email protected]