Inspired Through Art: Death and the Miser by Hieronymus Bosch, c. 1490

The artist Hieronymus Bosch is a mystery of Art History. His role in the Northern Renaissance has made him a curiosity who has been admired, copied, and perhaps disdained as a madman. His paintings are fantastical always and religious usually, but religious in a unique, sometimes troubling and psychologically dark manner. He left no written documents or letters that might explain his ideas about painting, but he is mentioned in the archives of the Illustrious Brotherhood of Our Blessed Lady, a Netherlandish religious confraternity. His father was an artist, as were three of his brothers. He rarely dated his paintings and there has been endless speculation about his work, his life, and the meanings of his paintings. However, his work is full of intense expressions of the urgency of the human condition, of which Death and the Miser is an exceptional example.

While most of Bosch’s famous works include many figures crowded into strange environments, this scene of the miser’s bedroom is focused on one person, the man who has lived a life of greed. He has come to the last moments of his life; the final battle for his soul is happening. We are given an opportunity to watch his life unfold in a simultaneous narrative.

In the foreground, we see him in the fullness of life depositing money into a lockable chest, the keys for which are hanging from his waist. Also hanging from his waist and passing through his hand is a rosary. This indicates a moral conflict: praying and hoarding wealth do not go hand in hand except in the disordered mind of the miser. The room includes other attributes of worldly prestige and gain such as armor and documents sealed in wax (likely contracts or loan documents). Remember that usury was, and is, the sin of lending money at exorbitant rates of interest, a likely source of income for this miser. In the chest a demon holds open the bag for the coins. Indeed, demons are everywhere in the room, lurking around and poking their heads from behind a curtain, from under the chest and from over the canopy. Above the canopy is a vaulted passageway and the bed seems to be receding into a void of darkness. Death itself, with the face of a skull, enters through the door with an arrow. In the bed the miser, emaciated with a sickly color, is at the end. It is time to for him to decide: repentance or damnation. Salvation hangs in the balance! Which will it be?

Fortitude

Fortitude is a virtue that is admired by even the non-religious. Even people who think temperance is for the overly pious, consider meekness a weakness, and scoff at humility believe that fortitude is a laudable attribute. For thousands of years, cultures have honored the courageous, recognizing the hero that finds the balanced mean between fear and impetuousness. As C. S. Lewis notes in The Screwtape Letters, people are “proud of most vices, but not of cowardice.”

The Catechism tells us, “Fortitude is the moral virtue that ensures firmness in difficulties and constancy in the pursuit of the good. It strengthens the resolve to resist temptations and to overcome obstacles in the moral life” (CCC 1808). Living a virtuous life requires courage. This is something we need to teach more frequently. The call to fortitude is not just in tales about knights or the stories of the martyrs, but in the life of every believer. The daily life of a Christian is not for the faint of heart.

For many years, catechesis shied away from presenting the Sacrament of Confirmation in “militaristic” terms. Avoiding language about battle and warfare, students were no longer taught about being “soldiers for Christ.” Some explain this language was omitted to avoid the sacrament being interpreted as a coming of age ritual or sign of maturity. If that was the case, the attempt has failed. Survey the average confirmation class and you will find most students, if not the catechist as well, has a misunderstanding of the sacrament along these lines.

Las virtudes del liderazgo cristiano

Un proverbio chino dice, “el hombre sin virtud es el inhumano”. Esta es una declaración muy radical, una que es políticamente incorrecta. Es una afirmación que escandaliza a nuestra obsesión igualitaria. Sin embargo, aunque la declaración sea bastante inofensiva para nuestros oídos, parece resonar en lo profundo de nuestra alma. ¿Por qué? Joseph Pieper, en su libro titulado Faith, Hope, Love (Fe, esperanza y amor) sugiere la respuesta al declarar que la virtud es “el mejoramiento de la persona humana”, “lo máximo de lo que puede ser el hombre”. “Es el reconocimiento de la potencialidad del ser de la persona. Es una perfección de su actividad”, y “la constancia de la orientación del hombre hacia la realización de su naturaleza, es decir, hacia el bien”.[1] En otras palabras, tanto un sabio chino como un filósofo contemporáneo están de acuerdo en afirmar que la virtud hace de la persona que la posee un ser humano realizado, un ser humano que está plenamente vivo. Por otro lado, una persona que no está creciendo en la virtud es una persona cuyo ser moral y espiritual está atrofiado.

Todos deseamos ser plenamente vivos. Si tal es el caso, necesitamos aprender más acerca de las virtudes y practicarlas con celo. Entre todas ellas, la magnanimidad y la humildad son de la mayor importancia. Se habla sólo raramente de estas virtudes. No obstante, Aristóteles decía que la magnanimidad (literalmente, “la grandeza del alma”) es “la corona de todas las virtudes”, mientras que, para los cristianos, la humildad es la raíz de todas las virtudes. Sin la magnanimidad, las virtudes no alcanzan la plenitud de su potencial y sin la humildad, las virtudes se degeneran, convirtiéndose en vicios de autosuficiencia. La magnanimidad y la humildad son dos lados de la misma moneda, la cual se llama liderazgo cristiano. Siguiendo la iniciativa del erudito francés Alexandre Havard, quisiera presentar a la magnanimidad y a la humildad como dos virtudes que constituyen la esencia del liderazgo. Las virtudes naturales de la prudencia, la justicia, la valentía y la templanza son los cimientos del liderazgo; y las virtudes teologales de la fe, esperanza y caridad dan estructura a nuestra capacidad para dirigir. La magnanimidad y la humildad, en palabras de Havard, son “las virtudes de la grandeza visionaria y de la devoción al servicio.” [2]

Hace poco conocí a un líder de esta índole. Soy profesor de seminario y miembro del equipo formador. Hace un mes, fui con catorce seminaristas en un viaje misionero a Perú. Pasamos una semana en una parroquia llamada Santísimo Sacramento. Nuestro anfitrión es el rector de esa parroquia. Su nombre es P. Joseph y es originario de Wisconsin, pero fue ordenado en Perú y ha servido a su comunidad por más de veinticinco años. Llegar a conocer a P. Joseph fue un verdadero placer. He aquí un hombre lleno de celo apostólico, visión y humildad. La filosofía de vida de P. Joseph se podría resumir de esta manera: “No hagas pequeños planes porque no tienen el poder para inflamar a los corazones humanos”. A menudo repetía esa frase y vivía de acuerdo a ella. Es un volcán de ideas y programas nuevos. Sin embargo, lo que más desea es que “su” gente cumpla con la vocación que Dios les ha dado para alcanzar “el estado de hombre perfecto y la madurez que corresponde a la plenitud de Cristo”.[3] P. Fr. Joseph es un gran hombre y hace de todos los que se asocian con él mejores personas. Exhibe las cualidades del liderazgo cristiano: la magnanimidad y la humildad.

The Virtues of Christian Leadership

From the Shepherds: Love, Whatever the Cost

As we reflect in this issue of The Catechetical Review on “living the virtues,” we recall St. Paul’s words that faith, hope, and love remain, “but the greatest of these is love” (1 Cor 13:13). For the benefit of our catechetical readers, we are reprinting here the homily of his Holiness for the meeting of reflection and spirituality, “Mediterranean: Frontier of Peace” in Bari, Italy on February 23, 2020.

Catholic Social Teachings and the Virtue of Mercy: Living the Social Dimension of Christian Discipleship

Last year while preparing to speak at a diocesan event on Catholic Social Teachings (henceforth CST) I came across a link on the USCCB website that offered a series of quotes from Pope Francis on the CST. Thinking I might find a pithy quote to use in my address, I opened the file only to find that it contained an overwhelming 378 pages of statements from our Holy Father on various aspects of the CST. Following in the footsteps of Pope Benedict XVI, Pope St. John Paul II, and the other Popes of the modern period, Pope Francis has tirelessly devoted himself to proclaiming the CST.[1] When I look at the staggering amount of energy and ink that our recent Popes have spent proclaiming the CST, I am struck not only by the importance that they give to the CST but also by the way they locate the CST at the center of authentic Christian discipleship.

In this article, I recall some of the basic truths of the CST and explore their intersection with Christian discipleship in order clarify how these teachings should shape the life of every believer through the virtue of mercy. Viewing the CST in this way enables us to see how the CST can serve as a measuring stick for faithful discipleship by emphasizing specific truths that challenge us and guide us in our attempts to concretely imitate Jesus in our love for neighbor.

Dispelling Some Myths

Before exploring the central components of the CST and how they relate to our Christian discipleship, it could be helpful to dispel some common myths about the CST that can hinder people from adequately prioritizing and properly implementing the CST in their daily lives.

The CST are not the Church meddling in worldly affairs nor claiming authority over the political domain. The CST never lose sight of the proper distinction between Church and state and the respect that each sphere is owed by the other. Likewise, the CST never amount to the Church telling Catholics to vote for specific politicians or usurping the genuine citizenship of each Catholic.

The CST are not the Church acting like a know-it-all by claiming a competency in secular areas (such as economics, politics, or medicine) that are beyond the scope of the Gospel. In turn, the CST do not seek to offer concrete solutions to complex technical questions or practical problems in various human endeavors.

The CST are not peripheral teachings that align with certain political parties or other groups of people that embrace socialism and various ideologies. Dedicating oneself to these teachings never amounts to aligning oneself with a specific political party or secular ideology. Likewise, these teachings are not merely for a certain type of person, the so-called activist who feels compelled to right the wrongs of this world.

The CST do not make sense only for those people who have a certain lifestyle or advanced knowledge of political and economic theories. You do not have to be a hipster or like granola to make the CST central in your life. You do not have to be professor of political philosophy in a tweed jacket or smoke a pipe to preach and practice the CST.

The CST are not a mountain of Magisterial documents devised to confront the political and economic issues created by the shortcomings of modernity. While the problems of modernity may accentuate the value of the CST, there are no historical limitations or cultural parameters to the origins and importance of the CST.

Contrary to these myths, the CST embody how the Church offers itself as an expert in humanity and as a guardian of the Gospel call to love our neighbor. The CST demonstrate the universal value of the Gospel by showing its intersection with every sphere of human life. At the same time, the CST are decisive for every Christian disciple who hears the great command to love our neighbor as Christ has loved us. They can provide us with the keys to understanding some central aspects of Christian discipleship by fostering the virtue of mercy in our social lives.

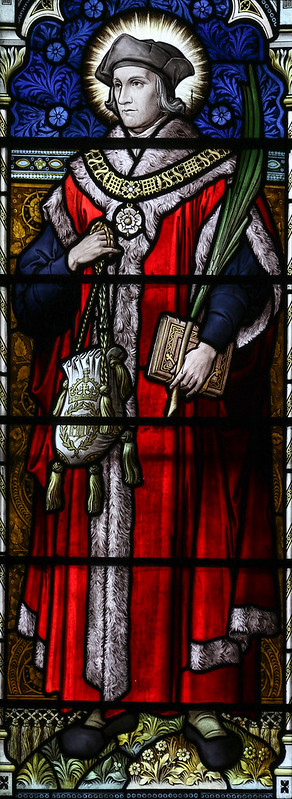

Editor's Reflections: St. Thomas More and the Struggle for Virtue

AD: The Best of Bishop Fulton Sheen Books & DVDs

To order any of these Bishop Fulton Sheen books or dvds, call 800-651-1531 or visit www.ignatius.com.

This is a paid advertisement and should not be viewed as an endorsement by the publisher.

AD: Earn Your MS in Education Completely Online in 12 Months

To learn more about our online graduate degree progam, click here, or call 800-783-6220.

AD: Free Downloadable Bi-lingual Discipleship Quad Kits

To learn more about and to download the free Discipleship Quad Kit in English click here, and in Spanish click here. Or call 740-283-6315.