In the first part of this series, we reflected on the life and times of St. John Vianney and the great obstacles he had to overcome to fulfill his mission to draw his flock into a closer union with Christ. He did so with humility and trust in the God who called him to this vocation. In this second part, Bishop Davies offers St. John Vianney as a role model for priests in their responsibility as catechists.

A great English Cardinal, Henry Edward Manning, may have inadvertently started a misunderstanding with regard to Saint John Vianney. In the Preface to the first biography translated into English, Cardinal Manning described the simplicity of the Curé of Ars as constituting “a rebuke” to the intellectual pride of the Nineteenth Century.[i] We can see how this was the case. However, this expression may have also led to the impression that Saint John Vianney was an anti-intellectual figure. This was not true. Pope Saint John Paul always expressed wonder at the Curé’s personal library of some 400 volumes, which is still preserved in Ars.[ii] It gives the clearest testimony to his life-long commitment to study and to learning. With the help of these substantive tomes, he prepared his preaching and catechesis, the sole aim of which was to dispel ignorance and lead a countless number to holiness. Theologians who attended his catechetical talks in later years were astonished by the sureness of his theological understanding when expressing complex ideas in short and vivid phrases.

A Catechetical Responsibility

When I was a young priest, it was sometimes suggested that priests might get in the way of the professional task of catechesis. The idea was circulating that the clergy should really leave this task to experts. I have no doubt that many priests may indeed lack the pedagogical knowledge and the skills of a fully trained catechist; however, we must never doubt that every priest in his pastoral ministry is called to be a catechist. In the training catechists receive, it must surely become one of their own tasks to assist priests, and indeed the bishops, in carrying-out the catechetical task entrusted to them. In Catechesi Tradendae, St. John Paul II echoed the teaching of the Second Vatican Council in declaring the bishop to be the catechist par excellence. If there were any danger that this might be understood merely as an “honorific title,” the saintly Pope John Paul wrote to bishops: “You are the ones primarily responsible for catechesis … Accept therefore what I say to you from the heart … let the concern to foster active and effective catechesis yield to no other care whatever in any way” (63). This great saint of our own life-time could not have been more emphatic when he added, “You can be sure that if catechesis is done well in your local churches, everything else will be easier to do.” And of priests he wrote with equal insistence: “I beg you, ministers of Jesus Christ: Do not, for lack of zeal or because of some unfortunate preconceived idea, leave the faithful without catechesis. Let it not be said that ‘the children beg for food, but no one gives it to them’” (64).

Preparations for Teaching

It was not natural giftedness that led St. John Vianney to give such prominence to catechesis in his rural parish. He was far from being a natural academic, yet he imposed on himself the absolute duty of going over and over again the doctrine of the Church and the writings of the great saints. In his struggle to study, we can recognize our own life-long task to grow in all the knowledge and skills that will help equip us to pass on the faith of the Church. It wasn’t for any human applause that the Curé did this for over four decades.

He preached each Sunday with catechetical intent. In the beginning, he had few noticeable results and no encouragement. We know he set up his desk in the sacristy where he studied his books, prayed before the High Altar, and then wrote laboriously sometimes for seven consecutive hours late into the night. The lack of appreciation of the preaching and teaching that he struggled to write out in full and then memorize is seen in one, single fact: most of his sermons—including most of what he wrote about the love of God and the Eucharist—were burnt by his assistant pastor. It seemed that, on paper, they were of no lasting interest to anyone. Perhaps the same fate awaits some of our best efforts!

The Curé of Ars also had to deal with his notoriously poor memory. We have descriptions of him finding himself lost for words because his memory suddenly failed. It was to the great amusement of his parishioners that he stuttered and stumbled over his words. He had been granted no natural eloquence, his voice being described as high-pitched and even squeaky. St. John Paul II noted how later in teaching catechism “he came to express himself more spontaneously, always with lively and clear conviction ….”[iii] St. John Vianney admired the oratorical power of the great preachers of his time, as when the famous Father Lacordaire had preached in Ars in 1845. He admired their oratorical skills, but he never shared them. We can only imagine what it cost him in his daily efforts to preach and to give catechesis to so few at first and then to so many. Yet, this great catechetical enterprise had its immense and lasting effect. It would have surprised him that his words, with their doctrinal accuracy and powerful images, would eventually find their way into the Catechism of the Catholic Church. The catechesis that had started for the children and adults of the parish—developing a daily pattern of classes—eventually addressed an international audience and also included the merely curious, the hostile freethinkers, and the visiting prelates and theologians.

However, it was his willingness to offer this testimony to the faith itself—rather than the particular skills that accompanied it—which remains the vital lesson for us today. During the time of the recent Synod of Bishops on the Family, I recognized how it was my own task as a diocesan bishop to give testimony to the beautiful coherence of Catholic teaching on marriage amid the voices of dissension and confusion, which so often seize the airwaves. I have absolutely no doubt that others could have done this better and with finer theological and pedagogical skills. However, the mission of bishop had been given to me, and it was necessary to raise my own voice as a pastor to clearly teach what was in danger of being lost.

The Catechetical Mission We Share

Amid the gathering confusion of the late 1960’s, Pope Paul VI saw it as his duty as the very Successor of Saint Peter and the Supreme Pastor of the Church, to make his own public, profession of faith, which became known as “The Credo of the People of God.” He did so by setting out in a coherent summary the faith of the Church—most especially in those areas of doctrine that were being doubted or contested. St. John Paul II left us in no doubt that “if the new evangelization is to be effective, our catechesis must convey the full truth of the Gospel, for that fullness of truth is the very source of our capacity to teach with authority: an authority which the faithful easily recognize when we address the essentials and deliver what we have received” (cf. 1 Cor. 15:3).[iv] Whatever context in which lay catechists are today called to work, no matter the communication skills of a particular priest or bishop, I want to propose there is a similar need for the voice of pastors to be heard giving testimony to the faith, especially where authentic doctrine is contested or even denied. Lay catechists are called to work alongside priests and indeed bishops in this mission of catechesis that has become so urgent today.

St. John Vianney has something to teach us about working together. The assistant pastor who was sent to Ars often patronized him and caused him many difficulties. Yet the Curé persevered in this collaboration, refusing (even when the opportunity was offered!) to have his troublesome co-worker removed. The Curé would also struggle to understand some of the administrative decisions of his bishop with regard to the Providence project. This was a project aimed at the Christian formation of the young; by Franciscan inspiration it had relied solely on Divine Providence for its material needs. The Curé would say with honest resignation “I cannot see God’s will in this, but if Monsignor does ….”

Amid the human difficulties we will inevitably encounter, we have in the Curé of Ars an example of the willingness to always work with others in the mission we share, even when we, like him, might not always find this easy. The Curé saw things from a supernatural point of view. He never lost this point of view. Neither must we.

In the last part of this series we will reflect on the catechist’s call to holiness.

The Rt. Reverend Mark Davies is the Bishop of Shrewsbury, in England, and is a member of the International Council for Catechesis.

Notes

[i] Cf. Abbe Monnin’s Life of the Curé of Ars, 1861.

[ii] See John Paul II, Retreat at Ars, Third Meditation, October 1986.

[iii] John Paul II, Letter to my Brother Priests, Holy Thursday 1986, no. 9.

[iv] John Paul II, Ad Limina Visit of the US Bishops, 27th February 1998.

This article originally appeared on pages 16-17 of the printed edition.

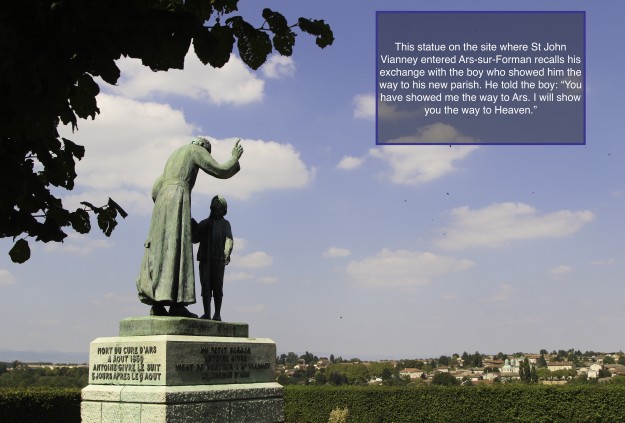

Art Credit: Photo by Fr. Lawrence Lew, OP. Creative Common license on Flickr.com.

This article is from The Catechetical Review (Online Edition ISSN 2379-6324) and may be copied for catechetical purposes only. It may not be reprinted in another published work without the permission of The Catechetical Review by contacting [email protected]