A Strong, Vibrant Tapestry: Cultivating Community Life in Your Parish

A strong community life within a parish does not just happen overnight. It is not the result of one specific curriculum or event but is woven together over time, creating a vibrant tapestry of unification in vision and way of life. When you enter a strong parish community for Sunday Mass, you feel alive, welcomed, and called to more. People of every age attend, the young and the old in necessary relationship, as a vibrant parish community is often multigenerational and a place people want to “come home” to and be part of. Together, they can weather the storms of staff and pastor changes or turbulent events. A strong community takes its strength from its intricate weave centered on Christ and his teachings and his sacraments, allowing for frays to be mended and the tapestry to grow.

A strong community life within a parish does not just happen overnight. It is not the result of one specific curriculum or event but is woven together over time, creating a vibrant tapestry of unification in vision and way of life. When you enter a strong parish community for Sunday Mass, you feel alive, welcomed, and called to more. People of every age attend, the young and the old in necessary relationship, as a vibrant parish community is often multigenerational and a place people want to “come home” to and be part of. Together, they can weather the storms of staff and pastor changes or turbulent events. A strong community takes its strength from its intricate weave centered on Christ and his teachings and his sacraments, allowing for frays to be mended and the tapestry to grow.

After nearly 20 years of serving parishes, we have found that helping build strong community is our passion. We have seen real fruit not only for those immediately in front of us but for multiple generations. In the January 2022 issue of The Catechetical Review, we wrote an article titled “No Family Is an Island: The Necessity of Community Living,” in which we focused on our personal experience of building a large young family community within our parish. What began as our deep desire to grow in our faith life through a strong community like we had in college became with God’s grace a thriving, faithful community that included nearly all of the young families in the parish. Once you experience the tremendous blessings of full Catholic community, it is hard to imagine life without it.

In this article we wish to engage the question of how to build parish community from the perspective of parish planning. We have been asked by many people in ministry, “What is your secret to building parish community?” And though it would be easier if there was just one great program to follow, book to read, curriculum to buy, or priest to beg to be assigned to your parish, we have found the answer to be intentional work and a slow and steady weaving of the parish tapestry.

The Complementarity of Man and Woman: Key Principles Informing Catechesis

The catechist’s chief task is to teach the true, good, and beautiful, focusing on illuminating the splendor of the deposit of faith. There are moments, however, when the topic that needs to be taught is a truth knowable for the most part by reason in addition to being knowable fully by faith. At this current moment in history, a primary truth at stake is the sexual difference of man and woman. The topic presses itself from all sides. Full-scale rejections of the reality of man and woman or distorted, reductive proposals abound. Yet, as in all eras of Church history, when a truth is being called into question, the Church responds by means of an even deeper contemplation and joyful proclamation of the unchanging truth, now fleshly enlightened.

The catechist’s chief task is to teach the true, good, and beautiful, focusing on illuminating the splendor of the deposit of faith. There are moments, however, when the topic that needs to be taught is a truth knowable for the most part by reason in addition to being knowable fully by faith. At this current moment in history, a primary truth at stake is the sexual difference of man and woman. The topic presses itself from all sides. Full-scale rejections of the reality of man and woman or distorted, reductive proposals abound. Yet, as in all eras of Church history, when a truth is being called into question, the Church responds by means of an even deeper contemplation and joyful proclamation of the unchanging truth, now fleshly enlightened.

The Church’s current response to confusion regarding man and woman is being fueled by positive developments in theological anthropology that have occurred during the past century. At their core is the articulation of the nature of man and woman via the notion of complementarity. This notion has emerged as the primary way of describing the reciprocal relationship between man and woman and the ordering of both to an interpersonal communion of love. Pope St. John Paul II is the most prominent contemporary promoter, with “reciprocal complementarity” being his preferred way of describing man and woman.[1] Given the necessity for catechetical initiatives to include the teaching of God’s plan for man and woman, it behooves one to ask the crucial question: What does it mean to say that man and woman are reciprocally complementary? With John Paul II as our guide, we will outline key principles of sexual complementarity that teachers of the faith must know in order to effectively catechize and evangelize our modern world. In short, man and woman, who are equal yet significantly different, are complementary because they are made for each other and for the fruitful expansion of love.[2] We will conclude by indicating a few points regarding man–woman complementarity and the new evangelization.

The Common Humanity and Equal Dignity of Man and Woman

The first and foundational principle of the complementarity of man and woman is their fundamental equality. Both are fully human persons; each one is an “I,” a someone not something, created in the image and likeness of God (Gn 1:26–27), willed for his or her own sake, created for eternal communion with God. Man and woman have the same rational human nature, involving an intellect and will, with all the concomitant essential properties that pertain to this nature (a soul as substantial form in hylomorphic unity with the material body). John Paul II affirms: “Woman complements man, just as man complements woman: men and women are complementary. Womanhood expresses the ‘human’ as much as manhood does, but in a different and complementary way.”[3]

Complementarity in general presupposes equality. For example, two nations’ economies can be complementary because both are nations, or two musical instruments can play together complementarily because both are musical instruments. This is even more true with human sexual complementarity: there can only be a mutual correspondence between man and woman if both are equally human persons. This is eloquently expressed in the biblical imagery of God forming Eve from the side of Adam—from his very substance—attesting to their primordial unity, equality, and intrinsic ordering to each other (see Gn 2:21–23).

Children's Catechesis—From Distrust to Empowerment: The (Problem with?) Opportunity of Parents

“Enabling families to take up their role as active agents of the family apostolate calls for ‘an effort at evangelization and catechesis inside the family.’” The greatest challenge in this situation is for couples, mothers and fathers, active participants in catechesis, to overcome the mentality of delegation that is so common, according to which that faith is set aside for specialists in religious education. This mentality is, at times, fostered by communities that struggle to organize family centered catechesis which starts from the families themselves.

—Directory for Catechesis, no. 124[1]

Parents. We rely on them to register their kids in our programs, to attend mandatory meetings, and to complete everything needed for sacramental prep. But fundamentally, we don’t trust them. Oh, we trust some of them. For the most part, though, we assume they aren’t reinforcing the faith at home—and have no interest in doing so. After all, they don’t even bring their kids to Mass most of the time. But what if the way we structure our programs encourages the very behaviors we don’t like?

Parents. We rely on them to register their kids in our programs, to attend mandatory meetings, and to complete everything needed for sacramental prep. But fundamentally, we don’t trust them. Oh, we trust some of them. For the most part, though, we assume they aren’t reinforcing the faith at home—and have no interest in doing so. After all, they don’t even bring their kids to Mass most of the time. But what if the way we structure our programs encourages the very behaviors we don’t like?

Our policies and procedures, our attitudes and approaches reveal that we don’t really believe parents can be the primary educators of their own children. Regardless of what the Church actually teaches about parents and the domestic church, we pastors, directors of religious education, and catechists all fail to trust. If we even allow at-home formation, frequently we don’t allow it in a sacrament year. When it really matters, we don’t have faith that parents can do it right.

The Roots of Distrust and the Desire for Control

The reasons for our distrust of parents are many. How do we know that they covered everything they were supposed to cover? How do we know that they taught doctrine clearly and accurately? How do we know that the child received authentic faith from their parents, who aren’t well formed?

It comes down to control, but we often forget how little control we have over what happens in the classrooms on our campus. Even a well-formed catechist with an excellent lesson plan and exciting manipulatives can fail to pass along the faith to every child in the room. How do we ever know everything was covered in a meaningful way for every child? The truth is, we don’t. If that’s the case on our campuses, then why are we so suspect of it happening in our families’ homes? If we ultimately rely on grace to operate in one place, why not in the other as well?

The Power of Community

In the summer of 2002, I had a health crisis, and left a community where I had been discerning a vocation to consecrated life. Feeling alone, and at a loss as to how to move forward, I went home to my parents to recover. About a year later, my mother developed ALS, and after eight months in hospice care, went home to Jesus. I was still in poor health, without work, and grieving. I could not foresee how the Lord would come to my aid. Then my sister invited me to come to Michigan to help her homeschool her seven children, to a town and parish where, she claimed, the Catholic community was amazing. I had been in many places where I’d experienced rich community and was a little skeptical. But I felt deep peace and even certainty that this was the right next step—at least for a little while.

In the summer of 2002, I had a health crisis, and left a community where I had been discerning a vocation to consecrated life. Feeling alone, and at a loss as to how to move forward, I went home to my parents to recover. About a year later, my mother developed ALS, and after eight months in hospice care, went home to Jesus. I was still in poor health, without work, and grieving. I could not foresee how the Lord would come to my aid. Then my sister invited me to come to Michigan to help her homeschool her seven children, to a town and parish where, she claimed, the Catholic community was amazing. I had been in many places where I’d experienced rich community and was a little skeptical. But I felt deep peace and even certainty that this was the right next step—at least for a little while.

Six months after I arrived in my sister’s town, some new friends asked me how I liked being there. I answered: “I’d like to be buried here.” I was not being morbid. Rather, after spending several years in Europe, Washington DC, and Canada, I’d at last found a place to settle, to rest in, to belong.

As I cared for and instructed my three very young nieces and nephew, my soul began to come to life again and let go of grief. Through my sister and her friends, I found myself adopted into a vibrant group of Catholic families, most of whom homeschooled. The parents were serious about living their faith and forming their children in it. I looked forward to the weekly mom’s coffee and play group, and soon I was “Aunt Liz” to a host of children.

One day not long after I’d arrived in Michigan, I stayed to pray after daily Mass at the parish, and the grief over my recent losses surfaced. Crying, I was surprised to see a woman I did not know tap me on the shoulder, asking if she could pray with me. I said yes, and that was the beginning of a beautiful Christian friendship. It was also my introduction to a community where praying with others was a normal occurrence. In those early days, I took advantage of all kinds of opportunities for healing prayer, basking in the love and consolation I received.

Because there was no space for me in my sister’s house, I was invited to live with a family from the parish who lived down the street. They became fast friends. The father of the family enlisted my service on the evangelization committee at the parish. We promoted and facilitated new small groups, and soon I was meeting folks of all ages from all walks of life and welcoming them into the community of which I was still a new member.

The more people I met, the more I was amazed by the witness of faith. Funerals at the parish were powerful experiences of hope, and I left them inspired and eager to run the race well. One image in particular remains emblazoned in my memory. It was the memorial Mass for the adult son of a couple who had already lost their other son. During the opening hymn, the father stood in the front row of the church with his hands raised, praising God with full voice. Tears streamed down his cheeks, and yet, his faith in God’s goodness and mercy impelled him to give thanks even in the midst of heartache.

Why Is There an Irish Pub in My Backyard?

When people learn that I have a full-on, legitimate Irish pub in my backyard, their first reaction is usually bewilderment, followed quickly by a deep curiosity. Then, when they see some photos and I explain what happens inside, they often want one of their own. The idea of a private backyard pub lands especially strongly with men. Often, people need to come and visit to truly understand what it is and how it works. Once they come inside and start to see it, curiosity sets in. Inevitably, the conversation shifts to the question of why. “Why did you do all this? And is your wife okay with it?”

When people learn that I have a full-on, legitimate Irish pub in my backyard, their first reaction is usually bewilderment, followed quickly by a deep curiosity. Then, when they see some photos and I explain what happens inside, they often want one of their own. The idea of a private backyard pub lands especially strongly with men. Often, people need to come and visit to truly understand what it is and how it works. Once they come inside and start to see it, curiosity sets in. Inevitably, the conversation shifts to the question of why. “Why did you do all this? And is your wife okay with it?”

It is no secret that friendship seems to be on the decline in this first part of the 21st century. According to a 2021 survey from the Survey Center on American Life, only 38% of Americans report having five or more friends. In 1990, the year I graduated from college, that number was 63%. Men seem to be suffering the most. Only 21% of men reported receiving any emotional support from a friend within the past week. Today, one in seven men report having no close friends at all.[1] I cannot say that one day I decided to build the pub to directly address this epidemic of loneliness. Its evolution was far more natural and organic. But this epidemic has certainly weighed heavily on my heart for a long time.

Born from Suffering

Long before the pub became a thing, it started with a couple of chairs on the side of our house. This modest, entirely unremarkable place somehow developed into a spot where people would come to sit quietly and talk about the challenges and heartaches of their lives. Sometimes it was a place of laughter and fun, but more often it was a place for thoughtful reflection, encouragement, and deep interpersonal encounters. For many years, I would sit there alone at night and post reflections on social media based on things I was hearing and contemplating.

To understand the genesis of the pub, however, you have to understand the backstory. Our family history is inextricably tied to my ongoing 22-year journey of medical challenges. It began with a cancer diagnosis in 2003. That lymphoma was supposed to be relatively easy to eradicate, but for some reason, it just didn’t want to leave quietly. Ultimately, it took five protocols of chemotherapy, six weeks of daily radiation, and two brutal stem cell transplants requiring months of hospitalizations and quarantine. I underwent 19 bone marrow biopsies and five surgical biopsies. Since then, I’ve had 23 other surgeries indirectly related to cancer, and about two dozen additional hospitalizations. I still average one or two per year. Throw in a devastating accident that broke my kneecap in half (requiring two surgeries) and a host of side effects—including tinnitus, chronic fatigue syndrome, recurring viral attacks, chemo-induced cognitive impairment, and radiation-induced cardiotoxicity that led to a heart attack and the placement of three stents in my arteries in 2021, and you start to get a picture of what my wife Margy and our five children have endured with me.

All of this helped make the pub what it is today. For over two decades, in our darkest hours of suffering, our family, friends, and neighbors consistently rallied around us in amazing ways. We’ve been the beneficiaries of countless meals, rides, free childcare, and miscellaneous acts of love.

Shortly after my initial diagnosis, the house we had leased for seven years was being repurposed, and we needed to find a new place to live. Not making much money at the time and facing a daunting and potentially fatal illness, we were in a difficult position. Providentially, there was an affordable house for sale in an up-and-coming neighborhood, but it needed a lot of work. It had good bones and a warm and positive history, but was a true fixer upper. Think weeds, neglect, clutter, and deferred maintenance. To illustrate this, one of the conditions of the sale was for the seller to remove the Volkswagen Beetle embedded in the ground in the backyard before we closed the deal.

Amidst our cancer battle, taking on a project like this was a daunting task. But our community rallied. Led by a saintly Holy Cross brother, over 200 people worked for three and a half months to get our house ready while I was receiving chemotherapy and radiation. Margy was often at my side during treatments, so my sister Mary, along with neighbors and friends, including the Sisters of St. Francis of Perpetual Adoration, temporarily “adopted” our children and joyfully cared for them. When we took our car into the mechanic, instead of fixing it he went out and bought us a new one. Let that sink in: our mechanic bought us a car. Years later, when that one broke down, a family friend bought us a brand-new minivan. People sent us anonymous gifts of every imaginable kind. I would never be able to remember and list all of the various ways our community blessed us during those dark times.

When my cancer came back for a third time in 2007 and I was forced into six months of isolated quarantine, the community organized a fundraiser at our local high school that raised $85,000—the exact amount needed to cover our expenses. Four hundred and fifty people attended.

If we lived another 10,000 years, we could never repay these people. Our gratitude is profound and overwhelming. This is a kind of gratitude that demands a response. Our pub ministry grew directly from this wellspring of love.

Motherhood: A Time of Conversion

When I had been a mother for about 20 years and was leading a women’s Bible study at church, I asked a group of mothers with young children to give me one word that would complete this sentence: Motherhood is a time of . . . “exhilaration,” “chaos,” “frustration” and “creativity” were some of the answers they called out to me. Then I shared with them a conclusion about motherhood that I had been coming to in those years. It was an idea I wish I had known when I first began having children, so I wanted to see if perhaps it could make a difference for them. I suggested that, above everything else, motherhood is preeminently a time of conversion. Why?

When I had been a mother for about 20 years and was leading a women’s Bible study at church, I asked a group of mothers with young children to give me one word that would complete this sentence: Motherhood is a time of . . . “exhilaration,” “chaos,” “frustration” and “creativity” were some of the answers they called out to me. Then I shared with them a conclusion about motherhood that I had been coming to in those years. It was an idea I wish I had known when I first began having children, so I wanted to see if perhaps it could make a difference for them. I suggested that, above everything else, motherhood is preeminently a time of conversion. Why?

We looked at a passage in St. Matthew’s Gospel to understand what conversion means, why it is necessary, and why motherhood offers women deep and abiding opportunities to experience it. In that passage, the disciples asked Jesus, “Who is the greatest in the kingdom of heaven?” (18:1). In reply, he made it clear that the more important question is: Who will get in? He said that those who seek to enter heaven must “turn [be converted] and become like children” (18:3). Even the disciples needed to understand that it was not enough to be an admirer of Jesus. They needed to consciously turn away from a life of self-reliance and become like children, with simple trust in and obedience to Jesus. Thus, he established the necessity of conversion. He illustrated the point when he called a child out of the crowd to come to him. The child obeyed, putting himself (literally) in Jesus’ hands, who then set the boy in their midst. Jesus told the disciples, “Whoever humbles himself like this child, he is the greatest in the kingdom of heaven” (18:4). So, what does all this have to do with motherhood? Jesus said it best: “Whoever receives one such child in my name receives me” (18:5). What did he mean?

To receive a child in the name of Jesus is what we do when we have our children baptized. A child who has been baptized into Jesus and his Church has been made part of his Mystical Body. In a very real way, Jesus himself has taken up residence in our homes through our children. He is there to save them—and us. Throughout our lives with them, we will hear Jesus call to us, always beckoning us to turn from the small, cramped, ill-fitting life of the self and become what we truly are: children of God. In other words, he will use our lives with our children to turn us from self-love to self-donation, making us ready for union with God. How will we, as mothers of children from infancy to adult life, hear his voice?

Catholic Schools— Empower Students to Be Family Evangelizers

Catholic school educators: heed the challenge! Extend your vocation response to include the family.

The vocation of the Catholic school teacher calls us to be catalysts that lead students to come to know, love, and serve God. In bygone times, home and school worked “hand in glove” to form a Christian character within the child. Some contemporary families are enthusiastic about pursuing that call. Many others, however, admit feelings of inferiority when it comes to being the spiritual formators of their children. They count on us to fill in the gaps that they perceive exist. Those parents need us to evangelize them.

What? You might say, I am already on overload! Lesson plans that incorporate various learning styles and mediums, differentiating instruction, student support meetings, mainstreaming, maintaining the student information system, extracurricular activities, faculty committee work, school duties (arrival, lunch, dismissal) . . . and the list goes on. Now you want me to add intentional evangelization of the family? I have no more time! Well, the good news is that you do not need more time if you apply the adage, “work smarter, not harder.”

First, identify projects for liturgical seasons and other faith-formation topics that are part of your normal teaching curriculum. Then, develop interactive lessons that lead from the head (ideas) to the heart (affection, emotion). You may engage the students in the lesson with activities like becoming a character in the Christmas crib scene, defining the gifts and fruits of the Holy Spirit with modern examples, depicting timeline events of the Triduum, building a Jesse Tree, or choosing a favorite proverb or “Jesus one-liner” from the Bible. Within instructional class time, teach the students how to find Scripture citations and where to look for information on Church-related themes like feast days, novenas, litanies, women in the Bible, etc. Finally, Work with the full class or in small groups to produce a single, unified class project. Display it in the classroom for the season.

Children's Catechesis — “Help Me to Come to God…By Myself!” The Need for the Child’s Independent Work in Catechesis

Those who have children and those who teach children have firsthand experience of the child’s need to do his own work. The very young child expresses this need quite bluntly: “I do it!” As the child matures, the expression becomes more nuanced and polite: “May I try?” In what appears to be a regression, the adolescent expresses the same need, though not with the same charm: “Why don’t you trust me?” I would argue that the child’s desire to “do for self” stems not from unruliness but rather from an intrinsic need impressed upon his nature by God himself.

Those who have children and those who teach children have firsthand experience of the child’s need to do his own work. The very young child expresses this need quite bluntly: “I do it!” As the child matures, the expression becomes more nuanced and polite: “May I try?” In what appears to be a regression, the adolescent expresses the same need, though not with the same charm: “Why don’t you trust me?” I would argue that the child’s desire to “do for self” stems not from unruliness but rather from an intrinsic need impressed upon his nature by God himself.

The Need Is in Our Nature

In the command to Adam to “subdue the earth,” God impressed upon the human soul both the dignity and the need for work. Reflecting on this passage from Genesis, St. John Paul II writes:

From the beginning . . . [man] is called to work. Work is one of the characteristics that distinguish man from the rest of creatures, whose activity for sustaining their lives cannot be called work. . . . work bears a particular mark of man and of humanity, the mark of a person operating within a community of persons. And this mark decides its interior characteristics; in a sense it constitutes its very nature.[1]

In this same section the Holy Father explains that “work” refers to “any activity by man, whether manual or intellectual.” Just as the person has a need to diligently build his environment, he has a similar need to intellectually build his knowledge.

The Holy Father’s insight that work is a constitutive need of our nature should cause us to pause and wrestle a moment with its meaning. Most certainly, the comment should not be taken to its extreme, suggesting that someone lacking the capacity for manual or intellectual work is somehow not fully human. Yet at the same time, the statement lends itself to a consideration of how personal work is in some fashion so integral to the human person that to deny him the opportunity is to violate his God-given nature.

The Child’s Need for Independent Work

During her many years of being with children, observing how they live, learn, and develop, Dr. Maria Montessori came to see that the child possesses the same intrinsic need for work as do adults. In fact, this need may be even more critical for the developing child. She writes:

The reaction of the children may be described as a “burst of independence” of all unnecessary assistance that suppresses their activity and prevents them from demonstrating their own capacities. . . . These children seem to be precocious in their intellectual development and they demonstrate that while working harder than other children they do so without tiring themselves. These children reveal to us the most vital need of their development, saying: “Help me to do it alone!”[2]

Think of the work that a baby chicken must do to peck its way out of its shell. Any attempt to help the tiny creature—to do for it what it must do for itself—results in the chick’s premature death. A similar phenomenon happens to the child when adults routinely overstep and do the work that the child can and must do for himself: he experiences a kind of psychic death. Some children become unnaturally timid, overly dependent, or abnormally compliant. Other children become rebellious against authority. In both extremes, the child’s interior freedom has failed to develop properly. “The child’s desire to work represents a vital instinct since he cannot organize his personality without working.”[3]

Catholic Schools — Building Support for Parents from Catholic Schools

Teachers, administrators, and others working in Catholic schools are devoted to their students. They want what is best for them. This is why they will want to increase the variety and level of support offered to parents.

Teachers, administrators, and others working in Catholic schools are devoted to their students. They want what is best for them. This is why they will want to increase the variety and level of support offered to parents.

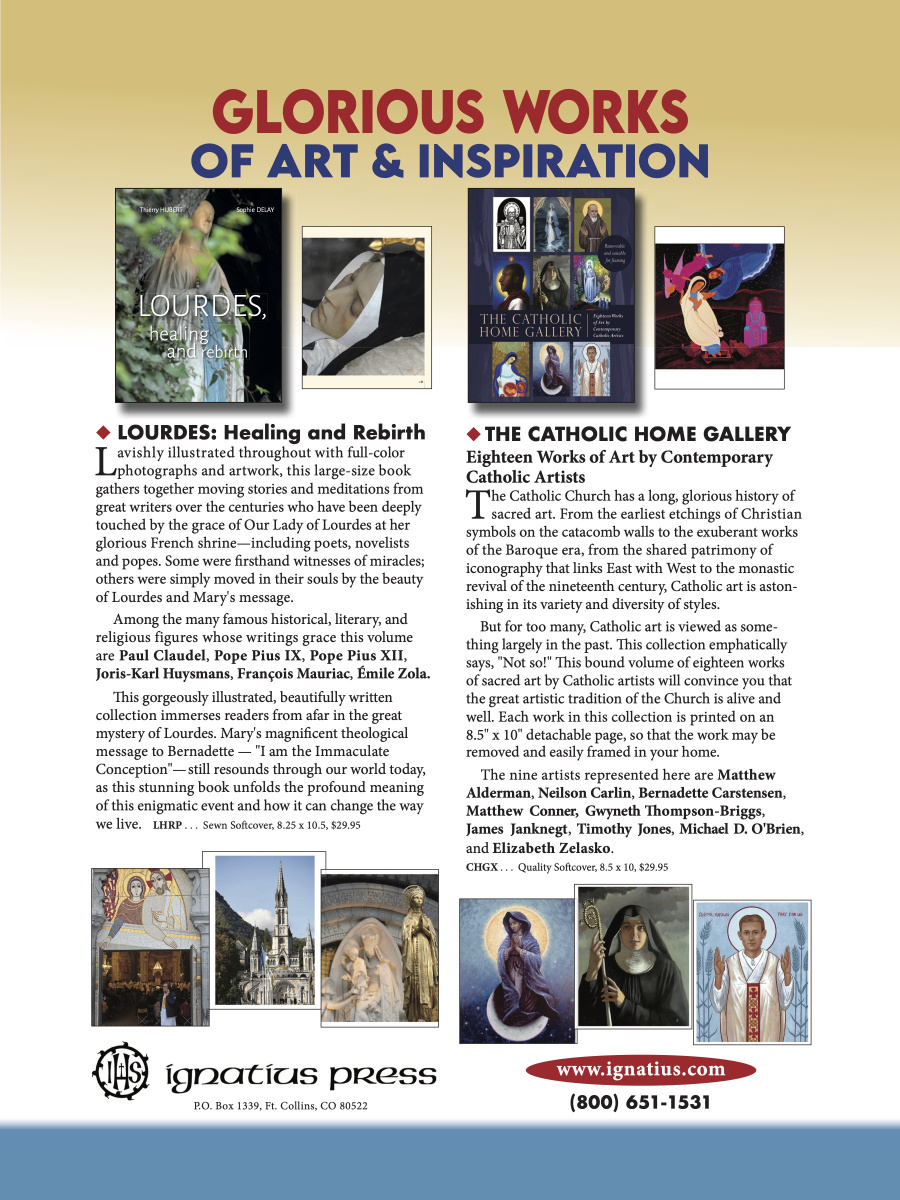

AD: Glorious Works of Art and Inspiration

This is a paid advertisement. To order these resources visit www.ignatius.com or call 800-651-1531.