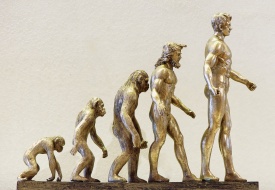

A powerful narrative exists within the popular culture that the advancements of modern science pose an existential threat to religious belief. This narrative, popularized by many influential authors, argues that scientific discovery is gradually upending the stranglehold Christian “superstitions” have held over the popular imagination. Nowhere is this apparent conflict more evident than in the field of evolutionary biology. For example, Christians maintain that we are made in the image and likeness of the Creator, yet many advocates of evolutionary theory claim humans are a meaningless twig on the evolutionary tree of life.

A powerful narrative exists within the popular culture that the advancements of modern science pose an existential threat to religious belief. This narrative, popularized by many influential authors, argues that scientific discovery is gradually upending the stranglehold Christian “superstitions” have held over the popular imagination. Nowhere is this apparent conflict more evident than in the field of evolutionary biology. For example, Christians maintain that we are made in the image and likeness of the Creator, yet many advocates of evolutionary theory claim humans are a meaningless twig on the evolutionary tree of life.

This view holds such force that Pope Benedict XVI felt compelled to state in his inaugural Pontifical homily that “We are not some casual and meaningless product of evolution. Each of us is the result of a thought of God. Each of us is willed, each of us is loved, each of us is necessary.”[i]

At first glance, it may seem that Pope Benedict’s statement assumes that there is some inherent conflict between the science of evolution and the Catholic faith. However, to read it in such a way is to take him out of context. Benedict was concerned not about the science of evolution but rather the philosophies that attempt to reduce the human person to a mere “casual and meaningless product of evolution.” Regarding such atheistic evolutionary philosophies, Pope Benedict stresses their inherent incompatibility with the Catholic understanding of the human person, a concern voiced by many of his predecessors.

Evolution and Catholic Theology: A Search for Understanding

In terms of the science of evolution, though, Benedict explicitly does not view it as inherently incompatible with the Catholic faith. Rather, he sees a natural complementarity between the science of evolutionary theory and a Catholic understanding of creation. In a published series of homilies he gave in the 1980s, Benedict stated: “We cannot say: creation or evolution, inasmuch as these things correspond to two different realities. [The Genesis creation account] does not in fact explain how human persons come to be but rather what they are. . . . And, vice versa, the theory of evolution seeks to understand and describe biological developments. To that extent we are faced here with two complementary—rather than mutually exclusive—realities.”[ii]

For Benedict, an investigation into the biological connection man has to other organisms in no way diminishes what man is. Likewise, the understanding that humankind is the only earthly creature fashioned by God in the divine image is a reality that can enlighten and focus our scientific studies regarding the evolutionary emergence of mankind. This synergy is articulated in the Catechism, which states, “Our human understanding, which shares in the light of the divine intellect, can understand what God tells us by means of his creation though not without great effort and only in a spirit of humility and respect before the Creator and his work.”[iii]

It is important to recognize that this “spirit of humility” that the Catechism mentions operates in both directions. Scientists who expect evolution to explain man in his entirety are destined to fail to understand “what man is,” while theologians who wish to shoehorn the scientific evidence into a literal reading of Genesis 1 are destined to construct an impoverished theology. Both are asking too much of their respective disciplines. No discipline is able to capture the full scope of reality; rather, they all complement each other in the search for the Truth. There is not one truth as revealed by science that can then trump truth as revealed by theology. Rather, there is one Truth that all disciplines investigate in their own limited manner using their own limited methods and competencies. As John Paul II stated in an address to the Pontifical Academy of Sciences, the knowledge gained via science and theology “both come from the same Source and are to be brought into relationship with the first Truth.”[iv]

As such, any apparent contradiction between, for example, evolution and Scripture stems either from the fact that we do not properly understand the meaning of the scriptural text or we have overstated or dismissed the scientific evidence. In fact, the unity of knowledge is a promise that scientific inquiry, if pursued diligently and “in a spirit of humility and respect before the Creator and his work,”[v] will reveal truths about the world that complement what has been revealed to us through Scripture regarding God, creation, and mankind. It means an honest, competent investigation into evolution, done through the proper use of human reason, will lead us toward God rather than drag us down toward atheism.

Evolutionary Science and the Emergence of the Human Body

Within this framework, it is worth examining the scientific evidence for the evolutionary origin of humans. However, in any such effort it is important to emphasize the limits of a strictly scientific explanation. Because man is a spiritual being with an immaterial soul, the science of evolution cannot explain man in his entirety. It can, however, explain the emergence of man’s material body for, as Pope Pius XII stated in Humani Generis, it is within the competence of evolutionary science to inquire “into the origin of the human body as coming from pre-existent and living matter.[vi]”

While the field of human evolution is constantly changing with the continual discovery of new evidence, researchers have identified that a multitude of intermediate hominin fossil forms have existed over the past six to seven million years. (Hominin fossils are those fossils that are more similar to modern humans than to modern chimpanzees.) By and large, these hominin fossils are found in the temporal sequence one would expect if the modern human body had indeed evolved from other hominins. For example, there are at least seven different species ascribed to the genus Australopithecus. All of these fossils having been found exclusively in Africa from 4.5 to 2 million years ago (MYA). They display brain sizes similar to modern chimps but appear to have been relatively adept at bipedal locomotion based on their skeletal qualities.

Our genus, Homo, is thought to have evolved from one of the Australopithecus forms roughly two MYA. This was followed by the development of different forms classified in the genus Homo, including Homo erectus, that migrated out of Africa and settled throughout the Middle East and East Asia. A variety of Homo species such as Homo ergaster and Homo heidelbergensis remained in Africa and gave rise more recently to Homo neanderthalensis and modern humans. These are only a fraction of the advanced hominin species that have been found, but it is interesting that they are largely found in a temporal sequence that is consistent with the evolutionary development of the modern human physical form.[vii]

The Emergence of Man: Passage into the Spiritual Realm

What then of the human rational soul, that divine spark that sets us apart from the rest of God’s creatures? Given the immaterial nature of the soul (it does not evolve from matter and is immediately created by God), an evolutionary explanation is not available. As St. John Paul II points out, “The moment of passage into the spiritual realm is not something that can be observed in this way.”[viii] However, science is not completely silent on the matter, as John Paul II goes on to state that “we can nevertheless discern, through experimental research, a series of very valuable signs of what is specifically human life.”[ix]

These “very valuable signs” he is referring to can be found in the archaeological record, a record that suggests humans capable of symbolic rational thought have been around for quite some time. For example, roughly one hundred thousand years before the present, artifacts that are indicative of creatures capable of symbolic thought—jewelry, engravings, and hafting techniques (the attachment of blades to handles)—began to make sporadic appearances at sites in Africa and the Middle East. This sporadic emergence gave way to a major increase in human cultural artifacts around forty to fifty thousand years ago as cave paintings and three-dimensional fertility carvings. Musical instruments began to appear at numerous European, African, and Indonesian sites. While it is difficult to reconstruct their entire behavioral repertoire, it seems certain, given the associated artifacts, that the individuals living around fifty thousand years ago (and most likely those living one hundred thousand years ago) were humans endowed with a rational soul.[x] As a result, any understanding of the emergence of man must take into account and explain our deep history.

Conclusion

The fossil intermediate forms; the history of symbolic artwork, jewelry, and complex tools; as well as the sharing of the same genetic defects in specific genome locations with other primates cannot be easily swept away without failing to “understand what God tells us by means of his creation.”[xi] But it is equally true that an evolutionary account of the emergence of man’s body cannot be used to sweep away the Catholic understanding of the human person. The fact that man’s body evolved does not imply that man is nothing more than a material being. Likewise, the evolutionary origin of the human body does not necessitate doing away with the belief that humans are created in the image and likeness of God, that humans are a unity of body and spirit. Nor does such an understanding deny the reality of original sin, that we have fallen and turned from God. There is nothing in the science of human evolution that demands such rejections. In fact, the fossil and archaeological records are not fine grained enough to reveal the specifics regarding when the first creatures made in the image and likeness of God emerged. While the archaeological record can give us some guidance on the possible timing, what exactly transpired at the dawn of humanity will likely remain forever hidden behind the veil of time. Pope Benedict summarizes the situation eloquently:

The first Thou that—however stammeringly—was said by human lips to God marks the moment in which spirit arose in the world. Here the Rubicon of anthropogenesis was crossed. . . . This holds fast to the doctrine of the special creation of man; . . . Herein lies the reason why the moment of anthropogenesis cannot possibly be determined by paleontology: anthropogenesis is the rise of the spirit, which cannot be excavated with a shovel. The theory of evolution does not invalidate the faith, nor does it corroborate it. But it does challenge the faith to understand itself more profoundly and thus to help man to understand himself.[xii]

While there is much collaborative work to be done by Catholic scientists and theologians in furthering our understanding of what it means to be human, successfully meeting this challenge requires bearing in mind two critical points. First, there is nothing in the science of evolution that is inherently contradictory to the Catholic understanding of creation, nor to the Catholic understanding of man as created in the image and likeness of God. Secondly, any discussions, if they are to be fruitful, must proceed from a place of deep humility and respect toward God and his creation.

Dr. Dan Kuebler is the Dean of the School of Natural and Applied Sciences at Franciscan University of Steubenville. He is the co-author of the book The Evolution Controversy: A Survey of Competing Theories (Baker Academic).

Notes

[i] Benedict XVI, “Homily of His Holiness Benedict XVI” (April 24, 2005).

[ii] Benedict XVI, In the Beginning: A Catholic Understanding of the Story of Creation and the Fall, trans. Boniface Ramsey, O.P. (Grand Rapids, MI: Erdmans, 1995), 50. Emphasis added.

[iii] Catechism of the Catholic Church, 299.

[iv] John Paul II, “Address for the 50th Anniversary of the Pontifical Academy of Sciences” (October 28, 1986), no. 4.

[v] Catechism of the Catholic Church, 299.

[vi] Pope Pius XII, Humani Generis, no. 36

[vii] For a brief, easy-to-read overview of hominin evolution, see: H. Pontzer, “Overview of Hominin Evolution,” Nature Education Knowledge 3, no. 10 (2012): 8.

[viii] John Paul II, “Message to the Pontifical Academy of Sciences: On Evolution” (October 22, 1996), no. 6.

[ix] John Paul II, “On Evolution,” no. 6.

[x] For a brief, easy-to-read overview of early human cultural evolution, see S. Wurz, “The Transition to Modern Behavior,” Nature Education Knowledge 3, no. 10 (2012): 15.

[xi] Catechism of the Catholic Church, 299.

[xii] Benedict XVI, “Schöpfungsglaube und Evolutionstheorie,” in H. J. Schultz, ed., Wer ist das eigentlich—Gott? (Munich: Kösel-Verlag KG, 1969), 232–45, quoted in the foreword to Creation and Evolution: A Conference With Pope Benedict XVI in Castel Gandolfo, trans. Michael J. Miller (San Francisco: Ignatius Press, 2008), 15–16.

This article originally appeared on pages 14-16 in the print edition.

Art credit: Public domain photo of statue depicting evolution growth from monkey to man from Pixabay.com.

This article is from The Catechetical Review (Online Edition ISSN 2379-6324) and may be copied for catechetical purposes only. It may not be reprinted in another published work without the permission of The Catechetical Review by contacting [email protected]